Air Travel in Art, Music and Film

IT’S SUCH A VISUAL THING, air travel.

Take a look some time at the famous photograph of the Wright Brothers’ first flight in 1903. The image, captured by bystander John T. Daniels and since reproduced millions of times, is about the most beautiful photograph in all of 20th century iconography. Daniels had been put in charge of a cloth-draped 5 X 7 glass plate camera stuck into Outer Banks sand by Orville Wright. He was instructed to squeeze the shutter bulb if “anything interesting” happened. The camera was aimed at the space of sky — if a dozen feet of altitude can be called such — where, if things went right, the Wright’s plane, the Flyer, would emerge in its first moments aloft.

Things did go right. The contraption rose into view and Daniels squeezed the bulb. We see Orville, visible as a black slab, more at the mercy of the plane than controlling it. Beneath him Wilbur keeps pace, as if to capture or tame the strange machine should it decide to flail or aim for the ground. You cannot see their faces; much of the photo’s beauty is not needing to. It is, at once, the most richly promising and bottomlessly lonely image. All the potential of flight is encapsulated in that shutter snap; yet we see, at heart, two eager brothers in a seemingly empty world, one flying, the other watching. We see centuries of imagination — the ageless desire to fly — in a desolate, almost completely anonymous fruition.

I own a lot of airplane books. Aviation publishing is, let’s just say, on a lower aesthetic par than what you’ll find elsewhere among the arts and sciences shelves. The books are loaded with glam shots: sexily angled pics of landing gear, wings and tails. You see this with cars and motorcycles and guns too — the sexualization of mechanical objects. It’s cheap and it’s easy and it misses the point. And unfortunately, for now, respect for aircraft has been unable to make it past this kind of adolescent fetishizing.

What aviation needs, I think, is some crossover cred. The 747, with its erudite melding of left and right brain sensibilities, has taken it close. The nature and travel writer Barry Lopez once authored an essay in which, standing inside the fuselage of an empty 747 freighter, he compares the aircraft to the quintessential symbol of another era — the Gothic cathedral of twelfth-century Europe. “Standing on the main deck,” Lopez writes, “where ‘nave’ meets ‘transept,’ and looking up toward the pilots’ ‘chancel.’ The machine was magnificent, beautiful, complex as an insoluble murmur of quadratic equations.”

Still, you won’t find framed lithographs of airplanes in the lofts of SoHo or the brownstones of Boston, hanging alongside romanticized images of the Chrysler Building and the Brooklyn Bridge. I won’t feel vindicated, maybe, until commercial aviation gets its own ten-part, sepia-toned Ken Burns documentary.

Until then, when it comes to popular culture, movies are the place we look first. One might parallel the 1950’s dawn of the Jet Age with the realized potential of Hollywood — the turbine and Cinemascope as archetypal tools of promise. Decades later there’s till a cordial symbiosis at work: a lot of movies are shown on airplanes, and airplanes are shown in a lot of movies. The crash plot is the easy and obvious device, and more than 30 years later we’re still laughing at Leslie Nielsen’s lines from the movie Airplane. But I’ve never been fond of movies about airplanes. For most of us, airplanes are a means to an end, and often enough the vessels of whatever exciting, ruinous, or otherwise life-changing journeys we embark on. And it’s the furtive, incidental glimpses that best capture this — far more evocatively than any blockbuster disaster script: the propeller plane dropping the spy in some godforsaken battle zone, or taking the ambassador and his family away from one; the beauty of the B-52’s tail snared along the riverbank in Apocalypse Now; the Air Afrique ticket booklet in the hands of a young Jack Nicholson in The Passenger; the Polish Tupolevs roaring in the background of Krzysztof Kieslowski’s Decalog, part IV.

Switching to music, I think of a United Airlines TV ad that ran briefly in the mid 1990s — a plug for their new Latin American destinations. The commercial starred a parrot, who proceeded to peck out several seconds of George Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue” on a piano. “Rhapsody” has remained United’s advertising music, and makes a stirring accompaniment to the shot of a 777 set against the sky.

We shouldn’t forget the late Joe Strummer’s reference to the Douglas DC-10 in the Clash’s “Spanish Bombs,” but it’s the Boeing family that’s the more musically inclined. I can think of at least four songs mentioning 747s — Nick Lowe’s “So it Goes” being my favorite:

“…He’s the one with the tired eyes.

Seven-forty-seven put him in that condition…

Flyin’ back from a peace-keepin’ mission.”

Somehow the Airbus brand doesn’t lend itself lyrically, though Kinito Mendez, a merengue songwriter, paid a sadly foreboding tribute to the Airbus A300 with “El Avion,” in 1996. “How joyful it could be to go on flight 587,” sings Mendez, immortalizing American Airlines’ popular morning nonstop between New York and Santo Domingo. In November, 2001, the flight crashed after takeoff from Kennedy airport killing 265 people.

My formative years, musically speaking, hail from the underground rock scene covering a span from about 1981 through 1986. This might not seem a particularly rich genre from which to mine out links to flight, but the task proves easier than you’d expect. “Airplanes are fallin’ out of the sky…” sings Grant Hart on a song from Hüsker Dü’s 1984 masterpiece, Zen Arcade, and three albums later his colleague Bob Mould shouts of a man “sucked out of the first class window!” Then we’ve got cover art. The back side of Hüsker Dü’s Land Speed Record shows a Douglas DC-8. The front cover of the English Beat’s 1982 album, Special Beat Service, shows bandmembers walking beneath the wing of British Airways VC-10 (that’s the Vickers VC-10, a ’60s-era jet conspicuous for having four aft-mounted engines, similar to the Russian IL-62), while the Beastie Boys’ 1986 album Licensed to Ill depicts an airbrushed American Airlines 727.

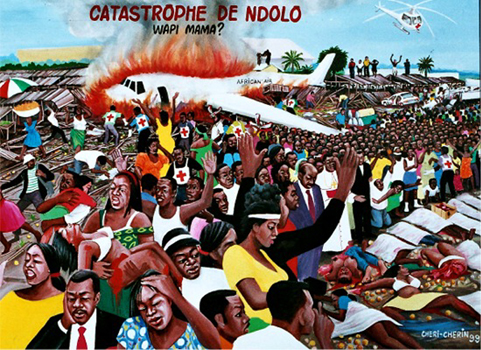

The well-known Congolese painter Cheri Cherin is one of very few artists to commemorate a plane crash on canvas. His “Catastrophe de Ndolo,” seen below, depicts a 1996 incident in Zaire, as it was known at the time, in which an overloaded Antonov freighter careened off the runway at Kinshasa’s Ndolo airport and slammed into a market killing an estimated 300 people — only two of whom were on the airplane (a precise fatality count was never determined).

Cheri Cherin’s “Catastrophe de Ndolo” (1999)

I asked Sister Wendy Beckett what she thought of Cherin’s non-masterpiece. You probably remember Sister Wendy — art historian, critic, and Catholic nun — from the PBS series a few years ago. “A splendidly gory recreation,” she tells us. “We see a bloody, devastated marketplace marked with the hulk of a burning fuselage. Yet the true fury of the event is captured not in the fire and gore, but in the cries and gestures of the people. It’s the apocalyptic landscape of a Bosch painting seen through the anguished psyche of modern African folk art.”

In reality who knows what Sister Wendy might say. I made that up.

Cheri Cherin has nothing on a certain young artist whose pièce de résistance appears below. This work commemorates the horrific, completely fictional three-way collision between Swissair, American Airlines and TWA. I would date this to 1975 or so, when I was nine years-old.

Last but not least, the Columbia Granger’s Index to Poetry registers no fewer than 20 entries under “Airplanes,” 14 more for “Air Travel,” and at least another five under “Airports.” including poems by Frost and Sandburg. John Updike’s Americana and Other Poems was reviewed by Kirkus as, “a rambling paean for airports and big American beauty.” (And while I can’t seem to find it, I specifically recall an Allen Ginsberg poem in which he writes of the blue taxiway lights at an airport somewhere.) Subjecting readers to my own aeropoems is probably a bad idea, though I confess to have written a few. You’re free to Google them at your peril. Maybe it was the cockpit checklists that inspired me, free-verse masterpieces that they are:

Stabilizer trim override, normal

APU generator switch, off

Isolation valve, closed

Autobrakes…maximum!

Closing note:

Looking at that Boeing 727 tail section on the Beastie Boys’ Licensed to Ill album, there are several things that give it away as an American Airlines plane. First is the angled-off tricolor cheatline — red, white, and blue — visible just forward of the engine. Those obviously are AA markings. Then you’ve got the all-silver base — another tradition of that carrier — as well as the whitish, off-color section of cowling over and around the center engine intake. This section of cowling was made of a different material, so they couldn’t use the bare silver here, going with a grayish-white paint instead. This gave the tails of AA’s 727s a mismatched look. Oh, and lastly, notice the black lettering to the lower right of the flag. This is the precise spot where the registration decals went. It would say, for example, “N483AA” Except, in this case it says “3MTA3 DJ.” The DJ part is for Def Jam records. The “3MTA3” means nothing…. until you hold it in front of a mirror.