April 21, 2022

FLY ENOUGH, and every so often you’ll encounter this or that famous — or infamous — person.

Maybe it’s a pop star. Maybe a film star. Maybe a newscaster, an athlete, or a washed-up comedian nobody remembers (see below). Maybe it’s 1981 and you’re a ninth-grader, standing in baggage claim at the Los Angeles airport, and the actor known as “Mr. T” walks past you with his entourage.

As a pilot, I have the added thrill of not just seeing or perhaps sharing a row of seats with whomever it is, but being somewhat indispensable to whatever journey he or she is embarking on — be it a flight home from an awards show or a trip to rehab. They’re counting on me.

Or so it’s fun to think…

The thing about Mr. T is that he was short. Or shorter than he should have been, as I understood it. There’s always something about a celebrity that catches you off guard.

Spike Lee was on board once. This was a shuttle flight from Boston to La Guardia. Lee also is on the shorter side, but I knew that ahead of time.

Kevin McHale, the Hall of Fame basketball star from the Boston Celtics, is not short. One afternoon I was working a flight from Atlanta to San Francisco, and Kevin was sitting in first class. “You and me go way back,” I said to him. This was a reference to the days in the early 1980s when I followed every Celtics game, and McHale was the power forward of the team’s “big three” attack, along with Larry Bird and Robert Parish.

(As it happens, some years ago I was waiting to appear on a local television show, and I shared the green room with none other than Robert Parish. It was just the two of us, and we chatted for a few minutes. That was cool.)

About two months after the flight to San Francisco, I was standing at the gate in Boston waiting to board a plane to JFK, when I looked over and there, again, was Kevin McHale. “Hey!” I said. “I flew you out to San Francisco a couple of months ago!”

Kevin McHale didn’t seem impressed. I guess I don’t blame him.

Another time it was Dan Rather. “What’s the frequency, Kenneth?” I said to the captain. He didn’t get the joke. You probably don’t, either. It’s an old reference.

Dan Rather is old. I’m old. Everyone is old.

Kirk Douglas was certainly old. He lived to be 103. And although I never met or flew Kirk Douglas, I did carry his famous son, the actor Michael, on a run from JFK to LAX. I learned later that Michael had been en route to his father’s centennial birthday celebration.

I knew who Michael Douglas was right away, but in general my celebrity recognition skills are poor.

Kanye West was on my plane coming back from Zurich. I remember he walked aboard carrying a glass of cognac that he’d taken from the lounge. I was standing near the doorway, and as he passed I made some goofy remark about people bringing drinks onto planes. A flight attendant took me aside and told me the guy was Kanye West. I had only the vaguest idea who Kanye West was, and until that moment couldn’t have told you what he looked like.

Another night, there was a buzz among the cabin crew because “one of the Kardashians” was sitting in row two. I seemed to be the only person on the plane who didn’t know what a Kardashian was. I’d heard the name enough times, sure, but it didn’t mean much to me. I knew they were a celebrity family for some bizarre reason — though, to me, the name has always makes me think of an arms dealer or a Wall Street villain. When I looked over at row two, I saw a pleasantly dressed woman reading a magazine. This was a Kardashian?

Which one was it? I don’t remember.

At the gate in Los Angeles one morning, a couple come aboard and take their place in business class. They have a kid with them, a toddler. They’re conspicuous for a few different reasons. For one, their clothes and haircuts are — I don’t know how to describe it, exactly. Flamboyant, I guess is the word. The woman has plumes of hair going in all directions, like Sideshow Bob. The kid, who is maybe three, has a miniature version of the same hair, but in a more vertical, mohawk style. He’s wearing a brightly striped onesie outfit that appears to be made of silk. He’s kicking and fussing and screaming. Later I’m told that that the woman is the singer Alicia Keys, and the little troublemaker is her son.

Would you recognize the former news anchor Katie Couric? I didn’t, but she was on my plane a few years ago, and, long story short, ended up borrowing my iPhone charger. I gave Ms. Couric my card and told her to let me know if ever she needed help with a story about airplanes or airlines. One morning, not long afterwards, she called me at home, with questions about something that had been in the news. I forget what the topic was, and nothing ever came of it.

I flew the actor F. Murray Abraham out of Bucharest, Romania. This was a big one for me, because Abraham has the starring role in what, to me, is the funniest scene ever filmed for television. I’m talking about the Russian Tea Room scene with Louis C.K. during season three of the show “Louie.” You can view it here. The genius of this scene can’t be overstated. I wanted to tell the actor that, but I kept my mouth shut.

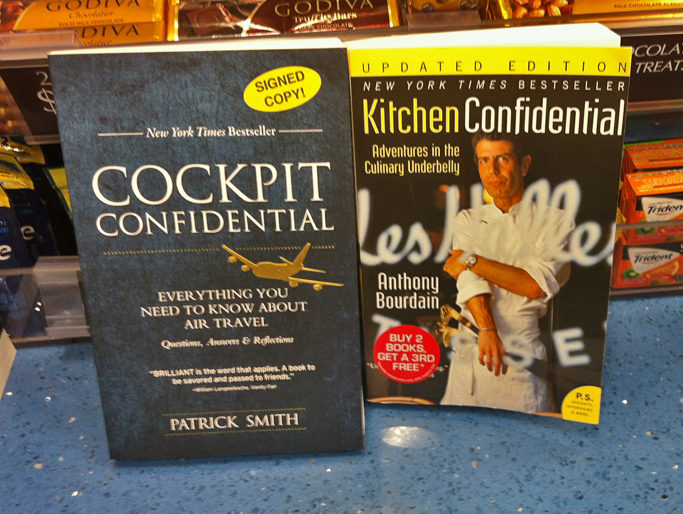

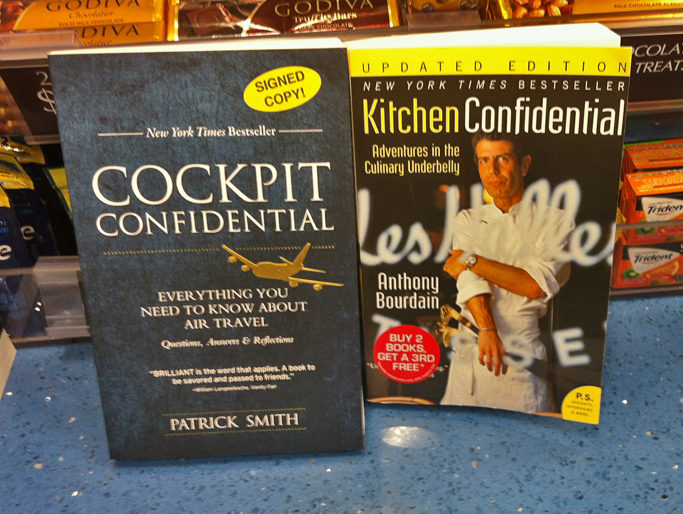

I did not keep my mouth shut the afternoon I flew Anthony Bourdain from Ireland to the U.S. This was in 2012, shortly before my book was published. The title of my book is, of course, a derivative ripoff of Bourdain’s famous book, “Kitchen Confidential.” I’d always felt uneasy about this, and here was my chance to let Mr. Bourdain know. “The publisher forced it on me,” I said to him, lying through my teeth.

He laughed.

And we haven’t even gotten to presidents…

I’ve met three presidents. None of them American presidents, but presidents nevertheless. The first of them was John Atta Mills, the semi-beloved leader of Ghana. Mills died in 2012, but during his tenure he rode aboard my airplane at least twice.

I also had the honor of meeting and flying the President of Guyana, Bharat Jagdeo. (Contrary to what my father and others seem to think, Ghana and Guyana are in fact different countries, on different continents, with different presidents to boot.)

Third on the list is Ellen Johnson Sirlief, Nobel Peace Prize laureate and former President of Liberia. I met her four times, including once at a reception at Roberts Field. On one of those occasions, I asked if she’d be kind enough to sign a copy of our flight plan. She obliged, writing her name in green ink at the bottom of the dot-matrix printout.

Things have worked out well for me, I think. Years ago, when I was puttering around over Plum Island, sweating to death in some noisy old Cessna, the idea that one day I’d be be carrying presidents in the back of my plane would have struck me as ludicrous.

Next we have the would-be presidents…

Doing this chronologically, we have to go all the way back a weekend afternoon in 1980. I’m at Boston’s Logan Airport, planespotting with a pair of my junior high pals, when who disembarks from a TWA jet only a few feet in front of us but Jerry Brown, then-governor (and, later, governor again!) of California. Brown was running for President that year along with Jimmy Carter, John Anderson and Ronald Reagan.

In addition to his political aspirations, Governor Brown, a.k.a. “Governor Moonbeam,” is known for his dabbling in Buddhism, his long liaison with Linda Ronstadt, and his appearance in one of the most famous punk rock songs — the Dead Kennedys’ “California Über Alles.”

Six years after that, on a Sunday morning in 1990, I’m standing at Teterboro Airport, a busy general aviation field in New Jersey, close to New York City. A private jet pulls up. The stairs come down, and out steps Jesse Jackson and several burly bodyguards. Jackson walks into the terminal, passing me by inches.

The following summer I’m back at Logan, using a payphone in Terminal E. Suddenly Ted Kennedy is standing at the phone next to me, placing a call. (Quaint, I know, in this age of wireless, but there’s the famous Senator, the brother of JFK, slipping dimes into the slot.) I’m talking to a friend, and I surreptitiously hold up the receiver. “Listen,” I say, “whose voice is this?”

“Sounds like Ted Kennedy,” she reckons. And it is.

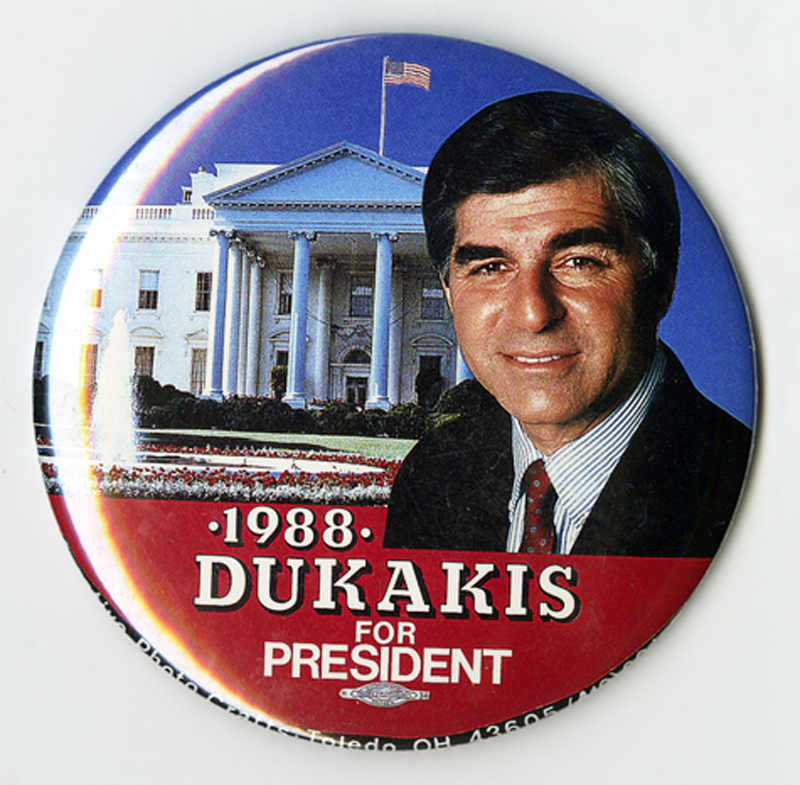

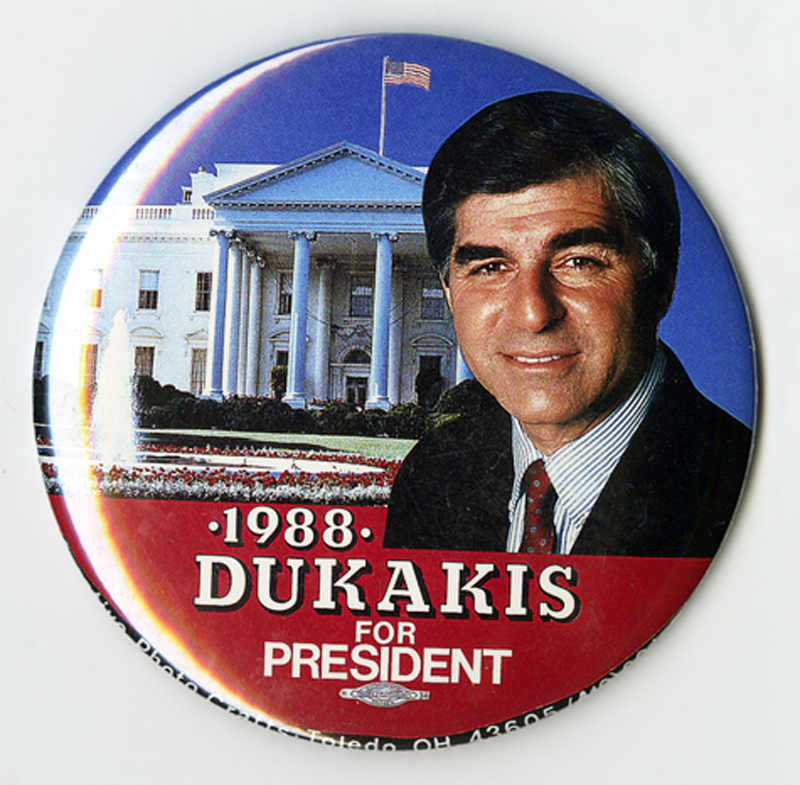

Next it’s 1994. Logan again, and I’m in the captain’s seat of a Northwest Airlink 19-seater, preparing for departure to Baltimore. Up the front stairs comes Michael Dukakis, who in 1988 had lost the election in a landslide to George Bush the Elder. He stops briefly behind the cockpit and says hello.

After we land in Baltimore, Dukakis thanks us for the ride and remarks, “Not a lot of room in here.” Even at 5’8″ he’s right about that. The Metroliner’s skinny, tubular fuselage earned it the nickname “lawn dart.”

“Yeah,” I answer, “It’s not exactly Air Force One.”

Meanwhile, intentionally or otherwise, the Duke has left a sheaf of important-looking papers in his seat pocket — probably because he’s run to a phone to cuss out his secretary for booking him on that stupid little plane with the annoying pilot. I carry the papers inside to the counter. “Here,” I say to the agent. “These belong to Mike Dukakis.” She looks at me like I’m crazy.

In 2012 I shared a shuttle flight from New York to Boston with Chelsea Clinton. She and her husband were sitting just a few rows ahead of me. At one point I was taking something down from the overhead locker when she passed me in the aisle. I was in her way and had to move aside. “Sorry,” I said. “Excuse me.”

“Thanks,” said Chelsea Clinton.

All of those people were Democrats. Rounding things off ideologically, I once had the controversial Supreme Court nominee Robert Bork on my plane. That was in the summer of 1991. Bork was riding in my rattletrap 15-seater from Boston to Nantucket.

That same summer, again to Nantucket in the same shitty plane, I flew David Atkins, better known to the world as “Sinbad,” the thankfully-forgotten actor and comedian who once had his own talk show and HBO comedy special. He sat in the back row of the Beech-99, surrounded by an entourage of beautiful women.

Okay, “thankfully-forgotten” is a cruel thing to say, even if he did wind up emceeing the Miss Universe pageant. Sinbad couldn’t have been friendlier, and in the Compass Rose restaurant at the Nantucket airport he bought me and my copilot chicken sandwiches, asking us for advice on what kind of airplane he should buy. We told him to invest in a Cessna Citation — a twin-engine executive jet — though I can’t remember why. I was making about thirteen grand a year at the time, and would have said anything for a chicken sandwich.

The great New York Yankees catcher Thurman Munson was killed at the controls of a Cessna Citation in 1979, but I don’t think we mentioned this to Sinbad.

Related Stories:

POLITICS, PLANES, AND PILOT BLACK MAGIC