Q&A With the Pilot, Volume 6

AN OLD-TIMEY QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS SESSION.

Eons ago, in 2002, a column called Ask the Pilot, hosted by yours truly, started running in the online magazine Salon, in which I fielded reader-submitted questions about air travel. It’s a good idea, I think, to touch back now and then on the format that got this venerable enterprise started. It’s Ask the Pilot classic, if you will.

Q: I appreciated your rant about excessive public address announcements at airports and during flight. However, announcements from the cockpit can’t escape attention. Seriously, can some of your fellow pilots please stay quiet? We get what we need from the cabin crew; we don’t need the pilots piling on.

I’m okay with pilot PAs so long as they are professional-sounding, informational, jargon-free and brief.

I make one prior to departure. I say our names, then I give the flight time (I always round the minutes to zero or five), the approximate arrival time, and maybe a short description of the arrival weather. The whole thing takes fifteen seconds.

The names part is just to remind people that actual human beings are driving their plane. There’s such a disconnect between the cabin and cockpit; most passengers never even lay eyes on the individuals taking them across the country or across the ocean.

I do not start in with, “It’s a great day for flyin,’ and we’ve got eight of our best flight attendants back there for your safety and comfort,” blah blah blah. That style of folky-hokey chatter is embarrassing.

Q: When I fly, I always love the ka-thunk sound of landing gear coming down, as it signals we’re almost to our destination. Sometimes I notice it comes down much closer to touchdown than other times. Why?

Planes normally drop their landing gear at around 2,000 feet above the ground, or when passing what we call the “final approach fix.” That’s maybe three minutes from touchdown, give or take. But it varies, depending on airspeed, spacing with other traffic, and so on. Lowering the gear has a significant aerodynamic impact, mainly in the adding of wind resistance (that is, drag). Sometimes we drop it early to help slow down.

I remember going into JFK early one morning. The controllers initially kept us high and fast, then suddenly gave us a “slam dunk” clearance straight to the runway. We put the gear out at like 5,000 feet to slow down and increase our descent to the maximum possible rate. No pilot likes doing this, as it’s noisy and maybe a little disconcerting for passengers. But under the circumstances, it worked great.

At most carriers the policy is to have the gear down and the plane fully configured for landing no later than a thousand feet above the ground. The idea is to minimize power and pitch adjustments and maintain what pilots call a “stabilized approach.”

Q: And please cure this stupid irrational fear once and for all: could pilots ever forget to deploy the landing gear? What are the safeguards to ensure this doesn’t happen?

Verifying that the gear is down and locked is one of the checklist items prior to landing. There are also configuration warnings that will sound if the plane passes a certain altitude without the gear (or wing flaps) in the correct position.

On top of all that, if you still somehow managed to forget, the whole picture would look and feel wrong. The plane’s attitude would be off, the power settings would be strange, the sounds would be different.

Pilots of small private planes are known to land with their gear up from time to time, but I can’t imagine this happening in a commercial jet.

Q: I recently flew on a 737-900, in row 13. I was surprised to find that there was no window in this row, although there was ample space for one. Why?

You see this on a lot of planes. Usually it’s because there’s some sort of internal component — ducting, framing, or some other structural assembly — that doesn’t allow space for a window. Some turboprops are missing a window directly adjacent to the propeller blades, and you’ll find a strip of reinforced plating there instead. This is to prevent damage if, during icing conditions, the blades shed chunks of ice.

Q: I often listen in to air traffic control on the internet. On the approach control frequencies, pilots will call in and identify themselves “with” a character from the phonetic alphabet. For example, “Approach this is United 515 at ten thousand with Alpha or “Approach United 827, five thousand feet with Uniform.” What does this mean?

Every airport puts out a broadcast that gives the current weather, approaches and runways in use, and assorted other info particular to the airport at that moment (some of it, to be honest, unnecessary). This broadcast, called ATIS (automatic terminal information service), is identified phonetically between A and Z.

On initial contact with approach control (or with ground or clearance control when departing), pilots are asked to report in with the most current letter, verifying they’ve listened to the broadcast and have an idea of what’s going on. Each time something is updated, the broadcast advances to the next letter. I will call in “with Sierra,” and the annoyed controller will snap back, “Information Tango is now up.”

I use the words “broadcast,” and “listened to,” because traditionally crews would tune to a radio frequency for ATIS, and transcribe its highlights onto a slip of paper. Nowadays, at most larger airports, it’s delivered through a cockpit datalink printout or is pulled up on our iPads.

For no useful reason, much of the typical ATIS report is abbreviated and coded using all kinds of nonstandard shorthand, and takes some deciphering. Aviation is frustratingly averse to the use of actual words, preferring instead a soup of acronyms and gibberish. I mean, it’s not the 1950s anymore and we aren’t using teletype machines to communicate.

Q: Tell us something weird?

What’s weird is that I haven’t been to a rock concert in thirteen years.

That’s super weird, really, considering how deeply into music I once was, and how many hundreds of concerts I attended. I can’t explain why, exactly, but I developed a later-in-life disdain for live performances. They suddenly felt goofy and weird to me: Am I watching or listening? Where do I stand? And none of the songs sound right.

You’ll tell me I’m just getting old Whatever the reason, I stopped going, even when the musicians are ones I love.

My last time at a show was in 2010, when I went to see Grant Hart in Cambridge. Prior to that we go all the way back to 2004, when I saw the Mountain Goats, also in Cambridge. Both times I was on the guest list, which made the idea of a night out more appealing. I’m not sure I would’ve gone otherwise. (Somewhere in there was Curtis Eller the banjo guy, and some symphonies, but those don’t count.)

That said, I’m told by a reader that the Bob Mould show in New Hampshire a couple of weeks ago was great, and at least half of the songs he played were classics from the Hüsker Dü canon. I wanna say that I wished I’d gone (the last time I watched Mould play live was in 1995). I was in Tanzania on vacation, so my excuse is solid, but even if I’d been home I may not have done it.

Concerts are one thing, but worst of the worst is any kind of live music in a bar or restaurant. There’s almost nothing I hate more. At least at a concert you’re there because, presumably, you enjoy the music of the artist you’re seeing. The music in a bar may or may not be anything you like. It’s intrusive, and conversation becomes difficult.

Here I’ll make this airline-related: On layovers in Accra, Ghana, I used to love hanging out at the poolside bar at the Novotel. It was such a chill place, with the most relaxing vibe. Then they brought in a piano player. Now the racket made talking almost impossible. He’d sing, too, and the beer mugs would crack when he hit the high notes. I had to find a new place.

EMAIL YOUR QUESTIONS TO patricksmith@askthepilot.com

Related Stories:

Q&A WITH THE PILOT, Volume 1

Q&A WITH THE PILOT, Volume 2

Q&A WITH THE PILOT, Volume 3

Q&A WITH THE PILOT, Volume 4

Q&A WITH THE PILOT, Volume 5

Q&A WITH THE PILOT, Volume 6

Q&A WITH THE PILOT, COVID EDITION

Portions of this post appeared previously in the magazine Salon.

PHOTOS BY THE AUTHOR

Decline and Fall of the U.S. Airport

Our airports are terrible, and our airlines are finding it harder to compete. We’ve done it to ourselves through flyer-unfriendly policies.

January 24, 2018

FORGIVE ME for repeating myself. In earlier posts, as well as in my book, I’ve emphasized the myriad ways in which U.S. airports pale in comparison to those overseas. I hate driving a topic into the ground, but my experiences over the past few days force me to revisit this:

The other day, traveling on vacation, I flew from Singapore to Amsterdam, with a connection in Hong Kong. The connection process in HKG went like this: I stepped off the first plane into a quiet, spacious, immaculately clean concourse. After a quick and polite security screening that took all of sixty seconds, I proceeded to my departure gate a few minutes away.

That’s it.

Compare this, if you dare, to the process of making an international connection in the United States of America. Imagine you’re a foreign traveler arriving in the U.S. from Europe or Asia, with an onward connection either domestically or to a third country:

You step off the plane and make your way to the immigration hall, which as always is packed to capacity. After standing in line for upwards of an hour, you’re photographed and fingerprinted before finally being released into baggage claim and the customs hall. Or maybe it takes even longer: after docking at the gate, airline station personnel inform you that due to extremely long lines at immigration, all passengers are asked to remain aboard for the time being.

Not to mention, if you’re coming from a country that’s not on the U.S. visa waiver list, you’ll need to have obtained a visa in advance just to begin this process, even you’re only passing through.

Your next task is to stand at the baggage carousel for twenty minutes and wait for your suitcase. American airports do not recognize the “in transit” concept, meaning that all passengers arriving from overseas, even those in-transit to a third country, are forced to claim and re-check their luggage. Once you’ve got your bag, another line awaits at the customs checkpoint, followed by yet another line at the luggage re-check counter.

Finally you’re released into the terminal. Of course, this building is used for “international arrivals only” — another of those peculiarly American airport concepts — and your connecting flight is leaving from a totally different terminal on the other side of the airport. To get there, you walk outside and spend fifteen minutes in the rain waiting for a bus.

And we haven’t gotten to the worst part yet: once you’ve reached the correct terminal, it’s time for security screening. The line at TSA is a good forty minutes long, the guards barking at people amidst the clatter of bins and luggage.

At long last you’re in the departure concourse, which is undersized, overcrowded, and, in the distinct fashion of too many American airports, louder than a football stadium. Babies are crying, CNN news monitors are blaring, and waves of public address announcements — most of them pointless and half of them unintelligible — wash over one another.

How long did all of that take? A solid two hours on some days. Welcome to the American airport.

Even if you’re not making a connection, the arrival process alone often takes over an hour. Back at Hong Kong, a passenger can be off the plane, through immigration and onto the train to Kowloon in fifteen minutes. I remember my last trip to Bangkok, and how I, an arriving foreigner, made it from the airplane to the taxi stand in less than ten minutes. BKK is one of the biggest and busiest international airports in the world, yet the waiting times at immigration can often be measured in seconds, never mind minutes.

Two years ago in a CNN poll of 1,200 overseas business travelers who’ve visited the United States, twenty percent said they would not visit the country again due to onerous entry procedures at airports, including long processing lines. Forty-three percent said they would discourage others from visiting. Separately, in a copy of Air Line Pilot magazine, U.S. Chamber of Commerce counsel Carol Hallett stated that “the United States risks falling behind Asia, the Middle East, and Europe as the global aviation leader.”

I’d say that battle was lost a long time ago.

To be fair, the scenario above is a worst-case to best-case comparison. Most overseas airports require a secondary security check for third-country connections, and there can be a secondary immigration checkpoint as well. Terminal transfers aren’t unheard of, and even some European airports go out of their way to make the travel experience tedious and confusing (CDG we’re talking to you). However, if we’re going to compare the typical connection experience in the U.S. versus the typical connection experience in Europe or Asia, the latter wins almost every time.

The crossroads of global air commerce today are places like Dubai, Istanbul, Seoul and Singapore. These are the places — not New York or Chicago or Los Angeles — that are setting the standards. They’ve got the best airports, the fastest-growing airlines, and the most convenience for travelers.

Some of their success is owed to simple geography. Dubai, for instance, is perfectly placed between the planet’s biggest population centers. It’s the ideal transfer hub for the millions of people moving between Asia and Europe; Asia and Africa; North America and the Near East. The government of the U.A.E. saw this opportunity years ago, and began to invest accordingly. Today, Dubai airport is one of the busiest, and its airline, Emirates, is now the largest in the world if you exclude the U.S. domestic market.

Not far from Dubai, Istanbul’s new airport is poised to become a similar mega-hub. Its hometown carrier, Turkish Airlines, flies to more countries than any other airline.

There’s not much we can do about geography. At the same time, there’s no excuse for the American aviation sector to have fallen so far. We’ve done it to ourselves, of course, through shortsightedness, underfunding, and flyer-unfriendly policies. The Federal government seems to treat air travel as a nuisance, something to be dissuaded, rather than a vital contributor of tens of billions of dollars to the annual economy. As a result our airports are substandard across a number of fronts, both procedurally and infrastructurally; our terminals are dirty and overcrowded; our air traffic control system is underfunded; Customs and Border Protection facilities are understaffed; passengers are groped and hassled to the point where, if that CNN poll is to be believed, millions of them will refuse to visit the country.

And although our physical location may not be ideal as a transfer point, there are still plenty of travelers moving between continents who can and should be connecting at U.S. airports aboard U.S. carriers — if only we weren’t driving them away.

Traveling between Australia and Europe, for example, or between Asia and South America, the U.S. makes — or should make — a logical transfer point. Hell, we don’t even try, beginning with the fact that our airports don’t allow for transit passengers.

Flying from Australia to Europe, to pick another example, a traveler has two options. He or she can fly westbound, via Asia (through Singapore, Bangkok, Kuala Lumpur or Hong Kong) or the Middle East (Dubai, Qatar, Abu Dhabi, etc.), or eastbound via the U.S. West Coast (Los Angeles or San Francisco). Even though the flying times are about the same, almost everybody will opt for the westbound option. Changing planes at LAX on the other hand, passengers have to stand in at least three different lines, be photographed and fingerprinted, collect and re-check their bags, and endure the full TSA rigmarole before slogging through a noisy terminal to the departure gate.

It’s a similar story traveling between Asia and South America. Europe to Latin America, ditto. Few passengers on these routes will choose to connect in the United States because we’ve made it so damn inconvenient. We can only guess at how many millions of passengers our carriers lose out on each year.

Insult to injury, airline tickets in America are taxed to the hilt. Overall, flying is a lot more affordable than it has been in decades past, but if it feels expensive, one of the reasons is the multitude of government-imposed taxes and fees. There’s an excise tax, the 9/11 Security Fee, the Federal Segment Fee, the Passenger Facility Charges, International Arrival and Departure Taxes, Immigration and Customs user fees, an Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service charge, and so on — a whopping 17 total fees! Airline tickets are taxed at a higher federal rate than alcohol and tobacco.

Finally, you should know that the government-run Export-Import (Ex-Im) Bank of the United States provides billions of dollars in below-market financing each year to carriers overseas, helping deliver hundreds of American-built aircraft at rates not available to our own airlines. This is one of the reasons Persian Gulf carriers such as Emirates and Qatar Airways have been able to expand so rapidly. U.S. taxpayers are in fact subsidizing the growth of carriers that compete directly with our own. Ex-Im’s assistance is helpful to Boeing, but it gives foreign carriers a competitive advantage.

Related story: WHAT’S THE MATTER WITH AIRPORTS?

Long Live the Airport Marquee

Harkening to an earlier age.

December 3, 2020

I WAS IN Madrid the other day and was able to snap the photograph above. This is the old Terminal 2, built in 1954, when the field was known as Barajas Airport. Like many old airport buildings, it instantly evokes another time, another era. I can easily picture an Iberia DC-8, or maybe a Caravelle, parked below the control tower, passengers in hats and suits climbing a set of drive-up stairs.

What I love best, though, is the airport name up on the facade. This was a common flourish in decades past, a nod to the platform signs often seen at railroad stations. The purpose, in this case, isn’t for orientation; obviously the airline passenger knows what city he or she has arrived in. That’s not the point. Rather, it’s a matter of greeting. The thrill of air travel isn’t so much the journey as it is the destination, and like the title frame in the opening credits of a film, this is a way of welcoming the visitor with a bit of drama and flair.

And I’m happy to report that location signs still exist, even at some of the newest and most modern terminals. You’ll find them on the apron side, facing the runways, or on the roadway side where passengers enter and exit the terminal. The latter are perhaps more common — the enormous lettering atop the departure hall at Bangkok’s Suvarnabhumi Airport being the most dramatic example. But it’s the apron-side marquees that I like the best, the ones glimpsed from the airplane window, adding a touch of excitement as you prepare to disembark.

I always get a picture when I can. Most of my collection is posted below. Reader submissions are welcome, and I’ll add the best of them to the page.

Welcome to Amsterdam.

Aloha, Honolulu

Bucharest’s Henri Coanda – Otopeni Airport.

A Royal Jordanian A320 at Cairo International.

Dubrovnik, Croatia.

The old terminal at BOM was replaced in 2014.

Dakar’s newly opened Blaise Diagne International.

Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe.

JRO airport, Tanzania.

“Town of the hurdled ford.”

Kenneth Kaunda International, in Lusaka, Zambia.

A down-home effort at Roberts Field, Liberia.

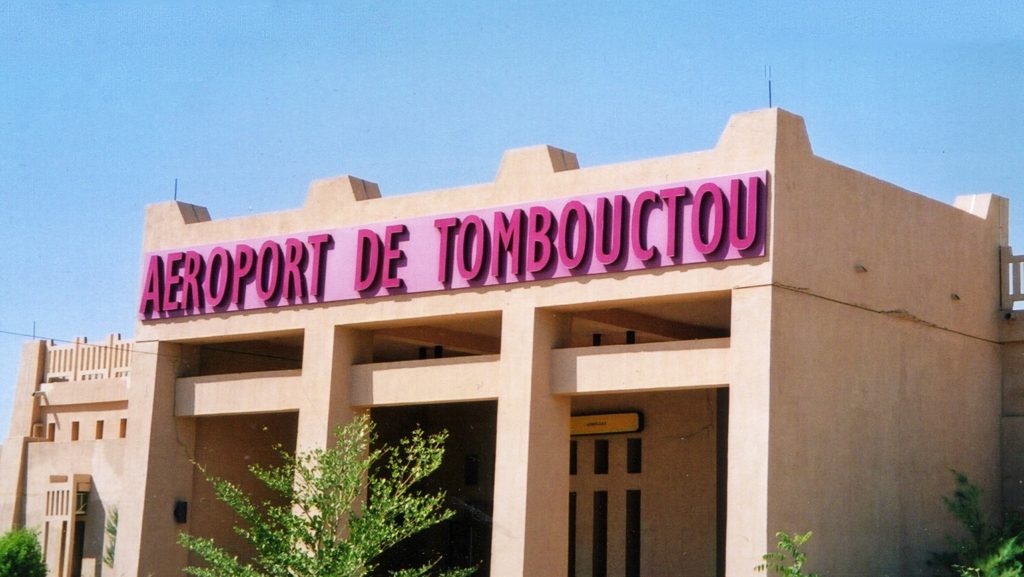

The Sudanese-style main building at Timbuktu, Mali.

Once a bustling stopover point, Gander sits empty.

Mexico City’s terminal 2.

The colorful Cheddi Jagan airport in Guyana.

Another shot from Cheddi Jagan. Notice the topiary.

Under the wing at Prague’s Vaclav Havel International.

Nnamdi Azikiwe is the airport serving Abuja, Nigeria.

John Paul II Airport in Ponta Delgada, Azores.

Your favorite pilot at Amsterdam-Schiphol.

Fes (Fez), Morocco. From Daniel Foster.

The old terminal at DCA. From Itamar Reuven.

Marrakech, Morocco. From Itamar Reuven.

Burbank, California. From Itamar Reuven.

Flamingo Airport, Bonaire. From Bruce Myrick.

Valetta, Malta. From Rick Wilson.

Tenerife South (TFS). From Rick Wilson.

Vienna, Austria. From Andrew Nash.

Zurich. From Andrew Nash.

Flying in the Age of Coronavirus

MOSTLY, this has been an exercise in stress. I suppose that’s an ambiguous term, so constituently we’re talking about fear, dread, and uncertainty. Not a fear of the virus. Coming down with COVID-19 isn’t what scares me. What scares me is what the airline business might look like by the time things settle out — whenever that might be.

Particularly astonishing was the speed at which things went to hell. In February, three friends and I were relaxing around a swimming pool in the Philippines talking about the size of our profit sharing checks and contemplating which aircraft we might bid in the months ahead. Within days — days! — the entire industry would be avalanched by panic and brought to a virtual halt.

The first three months were the worst. March, April, and May. Scant few flights were operating, and nobody had the slightest idea what lay ahead. These were some of the most stressful days of my life. Since then, things have settled into a certain routine. It’s not a happy routine by any stretch, and little about it feels normal. It’s just a routine.

If nothing else, I’ve kept busy. You might be surprised to hear that I’ve been spending more time aloft than ever. I’ve flown more in the past four months than in any four-month period of my entire career. Since June I’ve been to Europe twice, Africa five times, and back and forth across the country more times than I can count.

Normally I’m not the most ambitious pilot. The ancillary hassles of the job — the delays, the hellishness of airports, and the stress of commuting between the city I fly from (New York) and the city where I live (Boston) — encourage me to keep my schedule light and my blood pressure low. I might be on the road for twelve days in a month, logging around 70 pay hours. The average pilot aims closer to 80 and is gone for two weeks. But these aren’t normal times. Suddenly airports are quiet, delays are nonexistent, commuting is a breeze. It’d be perverse to say that flying is “better” than ever, but certainly it’s easier. Easier for all the wrong reasons, but it’s a way to keep my head up and maintain a sense of normalcy. So I’ve been doing it as much as I can.

Besides, there’s little else to do. What is life now but a sad morass of masks and placards and agitated people. So much of life has come undone that I dread the most innocuous of tasks and errands, like a trip to Trader Joe’s or a walk to the Post Office. And the extent to which the American public seems to have acquiesced to all of this leaves me fearful of the future. I’m not talking about wearing masks or following restrictions; I’m talking about accepting as normal a world that is anything but. More than once I have heard people shyly admit they are enjoying this. Hence, I’m happier on the job, where I feel engaged and useful, than I am at home, where I’m apt to stew and wallow.

Though here too, the damage is visible at every turn: the empty planes, the desolate concourses and shuttered shops. A stroll through an airport in the COVID era is, on the one hand, a relaxing one, free of the usual ruckuses and long lines. On the other hand it’s a way of beholding just how massively this crisis has impacted aviation. There’s a fine line between peaceful and haunting. It’s nice to be free of the noise and crowds, but for an airline employee it’s also a little terrifying.

Then we have the small things, the obstacle course of petty annoyances that now litter the travel experience. Like the endless stream of COVID-related public address announcements. Or the fact that every hotel room amenity now comes wrapped in plastic (because this somehow “saves lives,” and because if the world needs one thing it’s more plastic waste). Or needing to strategize over how to score food during layovers in locked-down cities.

There’s little to feel optimistic about, though at least I’m busy.

Not all pilots have this opportunity. Huge swaths of the pilot ranks have been sitting idle. Seniority is everything at an airline, and I’m high enough on the roster to avoid this fate, but many of my colleagues haven’t set foot in a cockpit in weeks or even months. Airlines are utilizing different fleets at different rates; at a given carrier, 767 crews might be busier than A320 crews, for example, or vice-versa. Some airlines have been operating long-haul cargo charters, which is keeping their biggest planes — and their pilots — surprisingly busy. Other fleets, meanwhile, have been shut down almost entirely, meaning those pilots are doing nothing.

The job itself is little different, but now has the added challenge of keeping focused in a time of angst and worry. Before every takeoff is a crew briefing, where we talk through any threats or difficulties that might lie ahead. Most of these spiels now include a line or two about concentration. “We’re all a little distracted, so let’s remember to follow procedures and stay disciplined…”

In the rows behind us, the customers savor those empty adjacent seats they always dreamed about. People are afraid, we’re told, and you read about the guy or woman who causes a commotion over masks and gets hauled off by the airport cops. But I’m not seeing this. On the contrary, passengers seem blithely content. There’s room to spread out, the flights are on time, and it’s a cinch through TSA. If you’re concerned about getting sick, a Department of Defense study released in October says the risk of catching COVID-19 on an airplane, as long as everyone is masked, is just about nonexistent. The air on planes has always been cleaner than people think, and it’s even cleaner now. In addition, cabins are being deep-cleaned after every flight, including a wipe-down of all trays, arm-rests, lavatories and so on. Those fancy business class menus have been curtailed — or “modified” as many airlines describe it — but otherwise there’s little not to like. Flying hasn’t been this comfortable in decades.

There’s a facetiousness in my voice when I say that, of course. For the workers, it’s hard to enjoy the ride when your company is losing twenty million dollars a day.

My take on this whole mess is no doubt tempered by earlier career hardships. I’ve been through two airline bankruptcies, one of which resulted in the company liquidating, and in the wake of the terror attacks of 2001 I spent five years on furlough. That’s airline talk for being laid off. I was in my mid-thirties at the time, in the middle of what customarily would be a pilot’s “prime-earning years.” Instead of saving money and making a good living, I scraped by as a freelance writer. This was, in a sense, an adventurous and successful half-decade; had I not lost my flying job, it’s unlikely the “Ask the Pilot” enterprise, or my book along with it, would ever have come to be. But despite the accolades, the book tour to Rome, the TV crews that often came to visit and the satisfaction of having used my improvisational talents to spin a little gold from a rotten situation, this was a long and financially bleak hiatus.

And when a pilot is out of work, for whatever reason, he or she cannot simply slide over to another airline and pick up where they left off. The way airline seniority systems work, there is no sideways transfer of benefits or salary. If you move to a different company, you begin again at the bottom, at probationary pay and benefits, regardless of how much experience you have. You lose everything. So any threats to our jobs or companies make us very nervous.

Five years on the street left me in a career no-man’s land, and upended my whole sense of self as a professional. Was I even a pilot any more? When I finally was called back, early in 2007, all I knew for sure is that I never wanted to live through that again.

And I didn’t expect to. Oh, sure, for any airline worker who endures a crisis — a furlough, a merger, a bankruptcy — nothing is ever again certain or taken for granted. No matter how rosy things are the moment, there’s always a hum of dread, a shoe waiting to drop, in the back of your mind. But this? This? Nobody foresaw a cataclysm of such speed or magnitude.

I have my ways of dealing with it. Others have theirs. On and on it goes.

PHOTOS BY THE AUTHOR.

Related Stories:

COVID CASUALTIES: OBSERVATIONS AND FAREWELLS

Q&A WITH THE PILOT, CORONAVIRUS EDITION.

30 YEARS ON: THE AUTHOR’S FIRST AIRLINE JOB.

Letter From Maho Beach

September 21, 2017

IF YOU’VE SPENT any time on the internet, you’ve seen Maho Beach, the thin strip of sand and surf abutting Princess Juliana International Airport on the Caribbean island of St. Maarten.

St. Maarten — or St. Martin — is part French and part Dutch. Princess Juliana (SXM) is in the Dutch section, and Maho sits just off end of runway 10. And when I say “just off,” I mean only a few hundred feet from the landing threshold. As arriving planes cross the beach, they are less than a hundred feet overhead. For an idea of how close this is, you can check out any of a zillion online pics. Like the one above. Or this one, or this one, or any of hundreds of YouTube videos. Unlike so many other scary-seeming airplane pictures you’ll come across, they are not retouched.

Thus, planespotting at Maho beach is an experience unlike any other in commercial aviation. Not that you need to be an airplane buff to enjoy it. For anybody, the sights, sounds, and sensations of a jetliner screaming overhead at 150 miles-per-hour, nearly at arm’s reach, are somewhere between exhilarating and terrifying.

How and why, exactly, are hard to understand. Is it the sense of danger, maybe? Or just the sheer novelty of it? Whatever it is, I felt it this past summer, during my first-ever flight into SXM. I landed a Boeing 757 there, coming in over Maho at about 2 p.m. on a perfect afternoon. It was fun being at the controls, but at heart, I didn’t want to be flying the plane. I wanted to be under it.

Our hotel was just around the corner, and as soon as I could I changed into a swimsuit and a t-shirt, and headed over.

The beach itself isn’t particularly pretty. It’s small, hemmed in between a pair of unattractive restaurants. The water is turbid, and there’s an ugly, two-lane road at the top of the sand. But that’s not the point, I guess. There are better places to swim, but none with a view like this one.

SXM isn’t a busy airport. Only a dozen or so jets land each day, and the nearby hotels and bars post the arrival and departure times. I was staying at the Sonesta, and they had a placard in the lobby listing the day’s flights. People tend to cluster whenever a plane is due — especially when it’s one of the widebodies coming in from Amsterdam or Paris. Air France brings in an A340. KLM was flying the 747 into SXM for years, but recently switched to the Airbus A330. The A330 is significantly smaller, but still breathtaking when it’s close enough to scrape the top of your beach umbrella. Charters from Europe are common too, using A330s, 787s, and other heavies.

I didn’t get to see any of those during the 90 or so minutes I spent there. I saw only smaller jets — a 737 and a couple of A320s. Still it was exciting. At Maho, pretty much any airplane gets your adrenaline going. And the noise will shake your bones. I also got to watch the same 757 that I’d brought in, piloted by the outbound crew, take off to the roar and applause of onlookers.

My landing at SXM wasn’t the smoothest one, if I can be perfectly frank, which I partly blame on the excitement of flying there for the first time. Procedurally, though, it was little different from landing anyplace else. The media will often speak of the Maho Beach experience from the perspective of the airplane — and wrongly so. Planes are described as “swooping in low,” or “low-flying,” or coming in at unusual angles. I found an online article describing SXM as “one of the world’s most dangerous airports.” Another cites the “risky approach” that pilots make to the runway. The Guardian writes that pilots are “forced to approach at low altitude.”

That’s just baloney. The runway at SXM is short, but there’s nothing different or unusual about the approach to it. The altitudes, speeds and angles that we fly all are normal. There happens to be a beach at the foot of the runway, but that’s the beachgoer’s concern, not ours.

And I don’t say that lightly. Jet blast and wingtip vortices at Maho routinely upends people and sends their belongings skittering into the ocean. Or worse. This past July, a 57 year-old woman from New Zealand was killed there after the blast from a departing 737 slammed her into the ground. The takeoff threshold of runway 10 is even closer to the shoreline than the landing threshold, and the tails of departing jets practically throw shadows over the sand. And the fact it was a little-old 737, and not a larger aircraft, attests to both the power of jet engines and the proximity of the beach. Check this out.

The woman was among a group of thrill-seekers who’d tried hanging onto the perimeter fence as the pilots throttled up. Hurricane-force thrust from the engines then slammed her into the pavement. Although she was the first fatality, several others have been injured over the years after recklessly grabbing onto that same fence — some of them sent tumbling head-first into one the concrete barriers that line the roadway — despite the presence of signs warning people to stay clear.

PHOTOS BELOW BY THE AUTHOR

Top-of-page photograph by Fyodor Boris

Note to readers: This story was published shortly before the island of St. Maarten, along with much of the Caribbean, was devastated by Hurricane Irma. Both Maho Beach and the adjacent airport were badly damaged by the storm. Our best wishes go out to the people of St. Maarten.

Welcome to Schiphol, the Airport of Quirky Charms

STORY AND PHOTOGRAPHS BY PATRICK SMITH

Update: November 10, 2016

OKAY, HERE’S WHAT IT’S NOT: It’s not Singapore-Changi. It’s not Seoul-Incheon. It’s not sparkly or fancy or architecturally exciting. It’s got bottlenecked corridors, low ceilings, and seemingly endless walks between concourses. And recent construction projects have made the passageways even more congested.

It is, however, clean, efficient and amazingly flyer-friendly.

Amsterdam’s Schiphol Airport is the place I’m talking about.

Schiphol has always been one of the top-scoring airports in passenger surveys, something that never made sense to me until recently, when I had a couple of long layovers that gave me time to really explore the place. AMS is the world’s 15th busiest airport overall, and one of the top five for international transfers. Keeping long-haul passengers happy is all about time-killing, and to this end Schiphol’s range of amenities is amazing:

My favorite are the “quiet areas” — relaxation zones decked out with sofas and easy chairs. Some are decorated with faux fireplaces. Others have artistically-inspired chairs with built-in iPads. Every airport should have some version of this. Noise and crowds are among the biggest stressors that travelers face, and nothing is more welcome than some peaceful corner to relax in. There’s also an in-terminal hotel that rents day rooms.

Amsterdam’s famous Rijksmuseum has a branch at Schiphol, right there in the terminal, with no admission charge. Directly next door is a sit-down library.

For children, the “Kids’ Forest” play area is bigger, brighter, and I have to say, just more fun-looking than most municipal playgrounds. Or maybe your tyke would rather play pilot in the awesome (if vaguely psychedelic) airplane replica, complete with puffy clouds, pictured at the top of this post.

The retail options are pretty much endless, and there’s also a full-service grocery store. If your layover is long enough, there’s a tour desk that sells half-day guided excursions into Amsterdam, with a pick-up and drop-off point just outside the terminal. For those staying in-country, the railway link into Amsterdam — and to points beyond — couldn’t be simpler. Tickets are purchased from kiosks inside the terminal, and the platform is only a short walk away via tunnel and escalator.

Amsterdam’s hometown carrier, KLM, is the world’s oldest airline, and on the second level, near the meditation room, is a hallway of historical KLM travel posters showcasing the carrier’s destinations and aircraft over the decades. There’s also that rarest of rarities at airports nowadays, an open-air observation deck, called the Panoramaterras. An outdoor deck is maybe not ideal considering the Dutch weather, but it allowed them to install that old KLM Fokker 100 as part of the scenery. You don’t need to be an airplane geek to appreciate the view and a chance for some fresh air.

Down in the central lobby, meanwhile, is one of the coolest airport retails shops around — at least in the eyes of some of us. The Planes Plaza sells plastic and die-cast models, toy airports, airline pins, books, and so on. In the hallway out front there’s an entire forward section of a former KLM DC-9 (open to passers-by, of course), as well as a main landing gear section and engine cowling from a McDonnell Douglas MD-11.

And when the weather is good (an iffy proposition most months of the year), the fun continues outside. This being the Netherlands, the airport’s perimeter is ringed by bicycle paths, one of which leads to Schiphol’s spotterplaats, designated zones adjacent to the runways where airliner enthusiasts gather with their binoculars and cameras — an activity that is all but banned in the U.S. (Airplane spotting is so popular in Holland that Schiphol’s website includes a spotters’ subsection.)

As you can see from the sign below, cyclists can ride from the airport clear into Amsterdam itself. How many big-city airport’s are accessible by bike?

Schiphol is pronounced “Shkip-hole,” by the way. The second syllable is short and flattened; it’s “Shkipple.” It’s not “Shipple,” and it’s definitely not “Shy-pole.”

No, there’s not a butterfly garden or koi ponds like the ones in Singapore, or the soaring ceilings and waterfalls you’ll find elsewhere. But what Amsterdam lacks in flair, it makes up for with a workmanlike functionality and plenty of quirky charms. It’s got something even the biggest and flashiest airports often lack: character.

NORTH LATITUDE

LETTER FROM AMSTERDAM, 1991

LIMPING INTO Centraal Station, I whisper quietly. “Skip-hole,” I say. “Skipple. Skip-ill.” I’m rehearsing the correct pronunciation of Schiphol, the name of Amsterdam’s airport, from where in a few hours I’m due to catch a flight home.

It’s midsummer of and I’ve been up for two days — every hotel, motel, guesthouse and hostel sold-out from Antwerp to Hamburg. I’d taken a pass on a second floor chamber at the Kabul, a Red Light hovel across from a condom store, napping instead at McDonald’s and listening to a seven year-old cassette of Zen Arcade over and over and over. Now the lobby of Centraal Station hovers above me with its overcooked façade of gables and filigree, like some great medieval fun house.

I’m limping because of a late-night collision with one of Amsterdam’s countless sidewalk posts. The city’s streets are lined with tens of thousands of knee-high iron bollards, the point of which, I think, is to keep cars from parking on the sidewalks (a mission for which they are semi-successful, depending which part of the city you’re in). Because they are black, and because they are knee-high, these bollards are a sensational invitations for injury. How the Dutch and their swarms of bicycles avoid mass casualties I’ll never know, but distracted by a flaxen blonde pedaling past me on the Leidseplein, I ambled straight into one. It got me just below the right kneecap. I could feel the tendons twist and buckle.

I move slowly and achingly into the station, where, if it’s any consolation, the ticket man seems impressed by my pronunciation efforts. He takes my guilders and smiles.

A half hour later, watching from a second-level airport restaurant, the KLM employees are the easiest to spot in their blue uniforms. Everything about KLM is blue. Even their jets, inside and out, are done up in blue — a two-tone of powder and navy. There’s something soothingly, inexplicably Dutch about it — the pudding shades lifted straight from a Vermeer painting. I look at the ticket counters — at the logo and the aluminum marquee, the stacks of KLM timetables and frequent flyer brochures– and I realize there’s no red. Try to find an airline that doesn’t have at least one shade of red as part of its identity. None of that here, just cool Dutch blue.

“Shkip-ohl,” I mouth silently. Airport workers on bicycles glide across the polished floor.

A few seconds later I’m asleep, my head on the greasy table and my knee throbbing.

Finally I’m at the counter, and the KLM woman’s badge — the KLM-ers are handling check-in for my Northwest flight — says “Meike,” which I assume is a first name, not a last, but I can’t be sure. Her white hair and milky features seem to go nicely with her blue vest — a perfect picture of efficient Dutch neutrality.

I hand over my pilot credentials: company ID, licenses, medical certificate (“holder must wear corrective lenses”), letting her know I’m entitled to ride along gratis in one of the extra cockpit chairs.

Jetliner cockpits can have many as five seats. Behind the pilots you’ll find one, and often two auxiliary stations, known colloquially as observer seats or “jumpseats.” A jumpseat might unfold in sections or swing out from the wall; or it might be a fixed chair not much different from those of the working crew. They can be occupied by training personnel, FAA inspectors, off-duty pilots commuting to work, and freeloaders like me. It’s an uncomfortable place to sit, most of the time, though probably not as bad as the middle seat in coach. Certainly the scenery is more interesting, and although pilots are known to whine for extended periods of time, there are no colicky infants. And, it’s free.

Or not entirely, as Meike tells me that I need to pay a departure tax, which is bad news because my knee is all but seized and the payment kiosk is two-hundred meters away. The distance means nothing to her, the Dutch airport employees simply coast through the terminal on their bikes. As I stagger away, I’m nearly flattened by one.

Next hurdle is a gate-side podium where a gangly security man in a cranberry-colored suit is grilling me, making sure I’m not a terrorist. He looks like he belongs at the Avis counter. This is one of those post-Lockerbie things, where you stand at the desk to be peppered with questions about battery operated appliances, the contents of your suitcase, and why you came here in the first place.

If he’s looking at me a bit strangely, it’s easy to understand why: I am 25 years-old. I have not slept or showered in almost three days, and I can’t walk. And I’m trying to convince this officious fellow that I’m an airline pilot deserving of a free ride home in the cockpit.

“You are a pilot?”

“Yes sir.”

“For who?” The takes my ID badge and fingers it warily. This is still what might be called the old days, and my small-time regional carrier, Northeast Express, isn’t one to take things too seriously. Its employee badges look like something you’d make at home. In fact, they are hand-assembled in a company trailer at the airport in Bangor, Maine. There are no holographs or fancy stamps or bar codes. He looks at my crookedly cropped photo and picks at the cellophane tape I’ve placed over the peeled laminate.

“Northeast Express,” I explain. “Or Northwest Airlink, like it says on our planes. We’re a code-share affiliate of Northwest. They have a hub here.”

“Northeast?”

“No, Northwest.”

“You work for Northwest?”

“No, I work for Northeast.”

“But…”

“Northeast Express. We fly feeder routes for Northwest.”

“So is it Northeast or Northwest?”

“It’s both!” I say in a voice a little too chipper.

“Really,” says the guard. “What kind of plane do you fly?”

“The Beech 99.”

“The what?”

“It’s a fifteen-seater. A small turboprop.” Embarrassment mixes with exhaustion.

“Small, eh?”

“About the size of a milk truck.”

“Yes, well. And where did you stay in Amsterdam?”

“McDonald’s.”

And so on.

My luck, they are using a 747 today instead of the usual DC-10. It’s one of the old -200s with a three-man crew. I love the 747 and savor every chance to ride on one. This time, though, I learn that every last passenger seat is occupied, which means I’ll have to spend the entire eight-hour trip upstairs on cockpit. Usually the captain will toss you back to a vacant seat, hopefully in first or business, but this time there aren’t any.

The cockpit of the 747 sits at the forward tip of the upper deck, at such a forward extremity of the giant ship as to feel entirely removed from the rest of it. Possibly, from the crew’s point of view, that disconnect is the ideal arrangement. Pilots fully grasp the gravity of their responsibilities, trust me, but a constant awareness that you’re sitting atop hundreds of thousands of pounds of metal, fuel, freight and flesh can be — and how to say this exactly — distracting. The cockpit is long, but surprisingly narrow and cramped for a plane so massive. Eight or more hours in the forward jumpseat, which does not recline, is the sort of thing that keeps chiropractors in business.

Worse, there’s another traveling pilot with us — he’s a United captain with a Dutch girlfriend, he tells us, who makes the crossing a couple of times monthly on his days off. This means there are five of us – the captain, first officer, flight engineer, and two jumpseaters, wedged into a room better suited for two.

But still, it’s a 747, that grandest of all jetliners. Despite my exhaustion and junkyard knee, I’m elated.

After strapping in, the other freeloader takes out his inflatable neck pillow and is sound asleep almost instantly. Propped in his seat, he looks like an unconscious accident victim in a neck brace.

We push exactly on time, and we’re in the air fifteen minutes later.

Out over the Atlantic it seems like the sun has hardly moved. And it hasn’t, so much, as we race westward, effectively slowing the passage of time. I can read the INS displays as they tick off the degrees of longitude and latitude.

At thirty degrees West the first officer is making a position report over the high-frequency radio. “Gander, Gander,” he calls, “Northwest zero three niner, position.” He’s got a clipboard full of dot-matrix printout on his left knee and a wedge of apple crumble on the right. A voice answers back, all reverb and crackly, a thousand miles away. Making a call over HF is a bit like offering up a prayer. You’re calling across some insane distance, hoping that somebody answers, and that they care.

The sunlight is white, oblique and directionless through the glass, like a spotlight from everywhere and nowhere. Outside temp shows minus 59. As the spectator, I’m both awed and heartbroken watching this crew of a 747 at work. An opportunity to sit here is irresistible. It’s like sitting in your favorite team’s dugout during a World Series game. But it carries with it a sort of voyeuristic shame. Forgive me, but it’s a bit like watching two strangers having their way with the girl of your dreams. You’re almost there, but the important parts are missing. You can watch but you can’t touch.

We are tracing a long, sub-polar arc toward eventual landfall at a gateway fix near Labrador. They’ve given us the northernmost track, one that will take us to nearly 60 degrees north latitude, practically scraping the glaciered tip of Greenland.

This far north, with clear weather and in the proper season (think April and Titanic), it’s not uncommon to see fields of icebergs drifting below, their wind-sculpted tops discernible from seven miles up.

Today there’s naught but gray ocean, the demarcations west of Greenwich passing invisibly, 60 cold miles at a time.

Which is fine since the view from the forward jumpseat of a 747 is terrible, unless you enjoy meditating on a wall of chipped zinc chromate, or else memorizing the lifejacket instructions embroidered onto the back of the captain’s chair. With all due love for the 747, the better jumpseat is on the old DC-10, where the aft left window extends from head-level to below the shins. You literally have a wall of glass to look through, and during steep approaches, or up over the Andes, the view is worthy of an Imax ticket.

My knee feels like it’s seizing, so I go for a walk.

I hobble downstairs and all the way rearward, past row 57 and up the other aisle. The plane is full and there’s crap all over the floor. People are asleep or watching the movie. I can’t tell what’s playing. A blurry bulkhead screen shows a distressed young woman crouching behind the fender of a pick-up truck.

I loiter near the rear galley and ask for a Diet Coke. A few feet away, waiting his turn for the lav, is a young guy in a purplish sweater. He strikes me as a straightlaced sort, maybe a law student or a kid who’d splurged for a bachelor party in Holland.

And he’s sweating, I realize. A nervous flyer? All flyers are nervous flyers, whether they admit it or not, but this is more serious. His J. Crew mock turtleneck (eggplant) is starting to blot at the armpits, and wet barbs of hair are sticking from his neck. Is this guy okay?

He’s the guy who in high school played on the hockey team and bullied me around. I’m thinking he’s got a Bulldog Café t-shirt somewhere in his luggage, which later he’ll give to his girlfriend who’ll wear it for the rest of the summer on Cape Cod.

I give him a half nod, then slide sideways towards the emergency exit. I turn and shift my weight so that I’m leaning against the door sill — my thigh held firmly against the boxy portion that contains the escape slide, and where it says DO NOT SIT.

And now the guy is eyeing me with a raised and quivering eyebrow, probably wondering which will pop open first — the lav, so he can relieve himself, or the cabin door, ejecting us both into the frozen tropopause. I should say to him: “Relax dude, I’m an undercover pilot, see?” Maybe flash him my trailer-made ID or a picture of myself in the cockpit of my ridiculous Beech 99, let him know it’s all gonna be okay.

But I don’t, and instead I put my hand on the big silver handle.

These door handles are designed for ease of use, I suppose, but they’ve always struck me as such retro-looking devices, clumsy and cartoonishly oversized. I’m thinking about this and tapping it with my thumb.

And now Eggplant J. Crew is on the verge of a full-bore conniption, his temples visibly throbbing. He fixes an angry gaze on me, his upper lip moist and trembling. Should I dare move that handle, he’s ready to spring, I can tell.

What Eggplant doesn’t know, and what, just for the fun of it, I choose not to tell him, is that neither of us could open the damn door if we spent all day trying. The doors on the 747, like the doors on most commercial planes, open in before they open out. At cruising altitude, with the cabin pressurized, there are probably 15,000 pounds of air pressure holding that door closed. If I jiggled the handle enough I might get a red light to come on and the pilot upstairs to drop his apple crumble, but the door is not opening.

After a minute he can’t take it any more. “Look,” he says, with a detectable tremor in his voice. “Could you please not touch that?”

“Sorry,” I say, pulling my hand back.

I take my Diet Coke and head towards the front again. As I hobble up the aisle, I shoot a quick glance at Eggplant, who seems to be calming down now that I’m leaving. “Take it easy.”

Little does he know this demented, limping person has a seat up front with the drivers.

Related Stories:

SOUTH LATITUDE: SEARCHING FOR SOUL IN FLORIDA AND BEYOND

WELCOME TO HIDDEN AIRPORT. UNEXPECTED PLEASURES AT A TERMINAL NEAR YOU.

DECLINE AND FALL OF THE U.S. AIRPORT

WHAT’S THE MATTER WITH AIRPORTS?

Planes, Pranks, and Praise: Ode to an Airport

Logan redux. From terrazzo floors to exploding soda cans, here’s Boston’s airport like you’ve never seen it.

STORY AND PHOTOS BY PATRICK SMITH

THERE AREN’T A LOT OF GOOD THINGS to say about US airports in general. They’re noisy, dirty, confusingly laid out, often in poor repair, and sorely lacking in public transport options. We’ve got nothing on the airports in Europe or Asia, many of which are architecturally stunning and jam-packed with amenities. If you’ve ever been to Singapore, Incheon, Munich, or Amsterdam, among many others, you know what I’m talking about.

But if we had to pick one of our own…

Washington’s Reagan-National has an excellent subway connection, and the terminal, with its sun-splashed central hall and vaulted ceilings, is one of America’s greatest airport buildings. The international terminal in San Francisco is similarly impressive. Orlando is clean, green, and well laid-out. Portland, Oregon, is many people’s favorite.

Nobody, though, ever mentions my hometown airport, Boston’s Logan International. And I don’t think that’s fair. It’s squeaky clean, well organized, and unlike the vast majority of US airports, it has an efficient public transport link to the city. It’s even got some flair: what’s not to like about the inter-terminal walkways, with their skyline views, terrazzo floors, and inlay mosaics?

A tour:

As an adolescent airplane nut in the late 1970s, I spent many a weekend at Logan. The place has come a long way since then. Large-scale renovations began in the 1990s with the third harbor tunnel project, and continue still.

The overall plan-view – a sprawling handprint of four independent buildings, terminals A, B, C, and E – remains mostly unchanged (what used to be terminal D is still there, but today it serves as a connector between C and E). Everything, however, has in one way or another been remodeled, rebuilt, or enlarged. Annexes and appendages sprout everywhere, covering what used to be vacant space. BOS has never been among the biggest or busiest airports, but it sees many more passengers than it used to. Some 29 million people fly through Logan each year, placing it 48th among airports worldwide. By number of takeoffs and landings, it ranks 26th globally and 17th in the United States.

Terminal C is probably the least altered. When I was a kid, this was the home to Delta, United, and TWA. Today, it belongs to JetBlue and United. JetBlue is currently the largest carrier at BOS, and has invested heavily in renovations. Still, there’s only so much room to expand, and the two main concourses are somewhat claustrophobic and overcrowded.

Terminal B, on the other hand, is substantially larger than it once was, its main tenants – American and US Airways – having spent millions over the years on expansion.

It’s gate B-32, incidentally, from which American Airlines flight 11 pushed back on the morning of Sept. 11, 2001. An American flag flies atop the jet bridge. Slightly to the north is gate C-19, similarly adorned by the Stars and Stripes – the departure point of United’s flight 175 that same morning.

The connector walkway between B and C, by the way, is one of Logan’s friendliest spots. I don’t mean the newer, elevated walkway; I’m referring to the old main-level passageway that begins near the gates used by Virgin America. Massport has installed a series of whimsically painted rocking chairs that face floor-to-ceiling windows with a view of the runways. There’s little foot traffic and, best of all, it’s blissfully quiet. It’s one of very few places at Logan – or any other airport for that matter – where you can completely escape the PA announcements, CNN monitors, and all the other noise pollution that that plagues America’s terminals. It’s a peaceful, sunny location to read, send texts, or otherwise relax.

Terminal E, as we know it today, used to be called the John A. Volpe International Terminal, named after the former Massachusetts governor. The building has doubled in size. The spacious, wood-paneled check-in hall is entirely new and arguably the airport’s handsomest spot.

Passing the TSA checkpoint, one enters the building’s older section, which is clean and functional, if otherwise unglamorous, with lots of gray aluminum and segmented windows staring toward Revere. This is the only terminal with customs and immigration facilities, and so it’s home to all of Logan’s overseas carriers. Though not exclusively: the cluster of gates at the eastern tip, once the home of Braniff and later Northwest, are today used by AirTran and Southwest.

On Logan’s south side is Terminal A. Completed in 2005, this is home to Delta (and to United’s Houston and Newark flights). On the outside, the structure is low-slung and unspectacular. From the roadway, one approaches a kind of airport glacier – a hulking slab of whiteness and glass that looks more like an office park or a mall.

On the inside, though, it’s sleek, roomy, efficient, and has the best harbor and city views of any of the four terminals (though somebody needs to explain the chocolate-colored carpeting). There’s state-of-the-art everything, including a laser-guided aircraft docking system and, airports being airports, an impressive gauntlet of shopping and dining venues.* The architecture is white, but the verve is green: Terminal A was the first LEED-certified airport building in America.

Terminal A rests on the site of the old Eastern Airlines terminal – a stately edifice of brown masonry that opened in 1969. Its replacement was perhaps overdue, but one thing I miss about the original is a certain drama, inside and out. Stepping into the lobby, your gaze was drawn upward toward a soaring, vaulted ceiling. It wasn’t beautiful, but it did something not many terminals do these days, imparting a sense of exhilaration and theater. The latticed façade and five-story archways bore a certain likeness to the lower curtain wall of the World Trade Center – and not by accident, for both were the work of architect Minoru Yamasaki.

One thing nobody misses, on the other hand, is the old MBTA Blue Line station. Logan was America’s first airport with a rapid transit connection (1952), and by the 1990s, the platform was literally falling to pieces. Its replacement is one of the T’s finest stations – even if few will be reminded of places like Hong Kong or Kuala Lumpur, where one is whisked to and from the city center without the need to step outside.

Alternately, the T’s Silver Line bus takes you directly to and from South Station. Though in either direction the trip takes longer than it needs to. There ought to be a designated airport bus that skips the intermediate Courthouse and World Trade Center stations. Another good idea would be to run two buses – one that goes to Terminals A and B, another to C and E. Passengers in a rush could take either and use the inter-terminal walkways.

The T connections aren’t ideal, but they’re far better than what most U.S. airports offer. And, inbound on the Silver Line, it’s free.

If you’re driving, Logan’s roadways aren’t as easy to navigate as they once were. In the old days, the terminal complex was linked by horseshoe-shaped highway that made a simple, one-way loop. You never got lost, but traffic jams were common. On busy evenings or holidays, making the circuit from A to E could take half an hour. The new roads are a Rube Goldberg affair of overpasses, underpasses, and switchbacks, but at least the gridlock is gone.

Then we have those climate-controlled pedestrian bridges, fetchingly inlaid with sea life mosaics designed by Somerville artist Jane Goldman. Previously, airline-to-airline transfers meant several minutes of sidewalk time and a ride on Massport’s shuttle bus. With the walkways now in place, there’s covered access – and a smidgen of ancient Rome – between any two carriers.

And rising above it all is Logan’s iconic control tower. This building opened in the early ’70s and is one of, if not the most, widely recognizable structures in all of Boston:

Segmented elliptical pylons that soar 250 feet into the air. They are sand-colored, but often turn amber in the sunset. Trussed between them, two-thirds of the way up, is a six-story platform of offices and workspace – an office building hung between two great goalposts. Its shoulders taper inward, and perched at their apex, like the head of a giant robot, is a 12-sided cupola crowned by a porcupine array of antennae and radar dishes.

I’ll tell you what I miss, though. I miss the old 16th floor observation deck.

On the bottom level of the tower’s workspace – either the 1st or 16th story, depending how you see it – used to reside one of Boston’s most unique public spaces: the airport observation deck.

The spectacularly poised lookout featured opposing sides of knee-to-ceiling windows and, arguably, the best view in town. To the north and east was a commanding vista of terminals, runways and taxiways; to the south and west, a sweeping panorama of the Boston skyline and waterfront. It’s a scant two miles from Logan’s perimeter seawall to the center of downtown, and thus, from the 16th floor, you observed the city and its airport in a state of working symbiosis.

From here, as an 8th grader in 1979, I saw Pope John Paul II touch down in a green-and-white Aer Lingus 747 named St. Patrick, then watched his motorcade disappear into the Sumner Tunnel before emerging again downtown. Passengers relaxed on carpeted benches while kids and families came on the weekends, feeding coins into the mechanical binoculars and picnicking on the floor. The idea of an airport evoking civic togetherness is hard to fathom these days, but the 16th floor possessed an element of that spirit, clinging to the now-vanished idea of an airport as a destination unto itself, like a park or a museum.

The deck had its regulars, and as a young teenager I was one of them. My friends and I would hop the Blue Line at Wonderland and spend the better parts of Saturday and Sunday at Logan. The 16th floor was our office, where we’d check in to unpack bag lunches and plan the day’s activities, which tended to blend our nerdier infatuations – taking pictures, logging registration numbers of planes – with the type of activities you might expect from adolescents: assorted rummaging, ransacking, and trouble-making.

We navigated our turf with a kind of muscle-memory intimacy. We knew the keypad combinations to most of the secure areas, and were on a first-name basis (“here come those pain-in-the-ass kids again”) with some of the airline ground staff. We’d sneak behind kiosks and dig through drawers and closets, helping ourselves to anything and everything affixed with an airline logo: stickers, stationery, boarding passes, and timetables. (At home, most of this detritus was tossed into a large aluminum foot-locker – a stash of collectible aerobooty that would doubtless garner thousands on eBay had I not thrown it away in the 1980s.) The parking lot atop the old Terminal A was another prime zone for pranks. More than one Eastern 727 or DC-9 had its wings and tail bombarded with snowballs from our rooftop launching pad.

Getting onto parked aircraft was something we accomplished regularly and with little resistance. It was an easy process of meandering through security, then staking out an arriving flight. After all the passengers had exited, we’d request a cockpit tour from the agent or crew. I remember a flight attendant taking us to see the lower-deck galley in a Delta L-1011 — riding down in the little elevator. Another time, a North Central pilot brought us into the tailcone of a DC-9 and showed us the data recorder.

Tired crews occasionally sent us down the jet bridge unattended. “Just don’t steal or break anything.” Or, if need be, it wasn’t beyond us to wander aboard without asking. We’d sit in the cockpit, going through imaginary takeoffs or pretending to be aloft over the ocean somewhere. Hunkered down over their desktop simulators, kids today think they have the edge on realism, but will never savor the visceral thrill of moving the actual throttles, knobs, and levers. Two friends and I once spent an entire hour sitting in the cockpit of a Northwest Orient DC-10. We’d simply walked down the jet bridge after everybody disembarked. Nobody had any idea we were there.

Once bored with the flight deck, we’d head back to the cabin, loading up our backpacks with barf bags, magazines, briefing cards, and cans of soda from the galley. We’d guzzle down that soda and were careful to save the cans. After amassing a six-pack or two, it was back to the 16th floor. There, in the bathroom sink, we’d fill the cans with water before sneaking into the fire escape. Within the tower’s north pylon, directly between the elevators, is a top-to-bottom spiral staircase. We’d learned to jimmy the door without triggering the alarm. Once inside, we’d lean over the railing and drop our water-filled cans the entire, 200-plus foot height of the shaft.

The cans would wobble, twist, and twirl, depending on the angle at which we released them. Like a pitcher feeling out the seams of a baseball for a slider or a curve, we had the different trajectories down to a science: hold it this way for a flat spin; tilt slightly for an end-over-end rotation. Off they’d go, and you’d hear the cans hissing as they accelerated toward terminal velocity, disappearing into a barely visible speck before impacting the concrete floor. Then came the sound, like a rifle shot echoing up the column. Often the cans would drift sideways and strike the lower floor railings or slam against the plumbing. Out of control, these wayward projectiles would ricochet madly, disintegrating in a white spray. Then we’d hop in the elevator for the post-crash investigation, marveling over the bizarrely crumpled cylinders and slivers of torn aluminum.

Over and over and over we’d let loose our water-bombs, emerging only for occasional quick scans of the tarmac, lest we miss Lufthansa’s daily departure for Frankfurt (flight 421, I still remember), or Swissair’s DC-10 (flight 129).

We’d also figured out a way, using wedges of cardboard, to raid the snack machines. Our heists were restricted to the lower shelves of the machines’ rotating dispensers, where the vendors, apparently catching on, began stocking some of the world’s most revolting treats. Back in Revere, my family’s kitchen cabinets held a year’s supply of stale Canada Mints that even our dog wouldn’t eat.

Up on the 17th floor, incidentally, was a lounge called Cloud Nine. For us, as 14-year-olds, it was one of Logan’s few decidedly off-limits spots, but itinerant flyers and off-duty employees were able to take in that same majestic view, enhanced by the buzz of an overpriced cocktail.

All of this is gone now. The observation deck, and Cloud Nine with it, were shuttered for good in 1989, ostensibly for security concerns.

The observation deck has become Massport’s Communications and Operations Center, with a suite of monitors and consoles that make it look like a miniature NASA command room. This is the headquarters of airport logistics, where a full-time staff of four coordinates everything from snow removal to emergencies. In the spot where I used to sit with binoculars, a Massport employee hovers in a telescoping chair, a display of incoming flights over his shoulder.

But the tower itself remains.

If an airport has one aesthetic obligation, it’s to impart a sense of place: you are here and nowhere else. And the Perini Construction Company’s lumbering control tower does this better than any airport building in the country. Looming overhead with anthropomorphic bravado (it really does resemble a giant robot) and staid New England resilience, this nameless old building is, then and now, the traveler’s touchstone and one of the city’s most exclamatory fixtures of identity. It says one thing, and says it perfectly: Logan Airport, Boston.

__________

* COMPLAINT: The sandwich wraps at the “Legal Test Kitchen” (LTK) annex are, in my opinion, terrible and overpriced. Nine dollars for a slab of chicken hidden in a tasteless padding of lettuce? And a lobster wrap…

Related Stories:

WHAT’S THE MATTER WITH AIRPORTS?