September 30, 2018

The Boeing 747 turns fifty years old today.

Smithsonian magazine has published an essay of mine about the plane for its “American Icon” feature. You can read it here. It appears in the magazine’s print version as well.

The longer, unabridged version is below.

FIFTY YEARS AGO, on the last day of September in Everett, Washington, the first Boeing 747 was rolled from the hangar. Onlookers were stunned. The aircraft before them, gleaming in the morning sunshine, was more than two-hundred feet long and taller than a six-story building.

An airplane of firsts, biggests, and superlatives all around, the 747 has always owed its fame mostly to feats of size. It was the first jetliner with two aisles — two floors, even! And enormous as it was, this was an airplane that went from a literal back-of-a-napkin drawing to a fully functional aircraft in just over two years — an astonishing achievement.

But this was more than size for the sake of itself. Boeing didn’t build the biggest plane of all time simply to prove it could. By the 1970s, a growing population craved the opportunity to travel nonstop over great distances. But no airplane was big enough, or economical enough, to make it affordable to the average person. Boeing’s four-engined 707 had ushered in the Jet Age a decade earlier, but with fuel-thirsty engines and room for fewer than 200 passengers, its per-seat economics kept ticket prices beyond the budget of most vacationers.

Enter Juan Trippe, the legendary founder of Pan Am. Trippe had been at the vanguard of the 707 project, and now he’d persuade Boeing that not only was an airplane with twice the 707’s capacity technologically feasible, it was a revolution waiting to happen.

He was right, even if vindication didn’t come easy. Boeing took a chance and built Trippe his superjet, nearly bankrupting itself in the process. Early-on engine problems were a costly embarrassment, and sales were alarmingly slow at the outset. But on January 21, 1970, Pan Am’s Clipper Victor made the maiden voyage on the New York–London milk run, and the rest, as they say, is history. With room for upwards of five-hundred passengers, the 747 introduced the economies of scale that, for the first time, allowed millions of people to travel great distances at affordable fares. Say what you want of the DC-3 or the 707 — icons in their own right — it’s the 747 that changed global air travel forever.

And it did so with a style and panache that we seldom see any more in aircraft design. Trippe isn’t the only visionary in this story; it was Boeing’s Joe Sutter and his team of engineers who figured out how to build an airplane that wasn’t just colossal, but also downright beautiful.

How so? “Most architects who design skyscrapers focus on two aesthetic problems,” wrote the architecture critic Paul Goldberger in an issue of The New Yorker some years back. “How to meet the ground and how to meet the sky—the top and the bottom, in other words.” Or, in Boeing’s case, the front and the back. Because what is a jetliner, in so many ways, but a horizontal skyscraper, whose beauty is beheld (or squandered) primarily through the sculpting of the nose and tail. Whether he realized it or not, Sutter understood this perfectly.

Joe Sutter and his creation.

It’s perhaps telling that today, strictly from memory, with only the aid of a pencil and a lifetime of watching airplanes, I’m able to sketch the fore and aft sections of the 747 with surprising ease and accuracy. This is not a testament to my drawing skills, believe me. Rather, it’s a demonstration of the elegant, almost organic flow of the jet’s profile.

It’s hard to look at a 747 without focusing on its most distinctive feature — its upper deck. The position of this second-story annex, which tapers rearward from the crown of the cockpit windscreen, has typically inspired descriptions like “bubble-topped” or “humpbacked,” which couldn’t be more insulting. In fact the upper-deck’s design is smoothly integral to the rest of fuselage. Compare the 747’s assertive, almost regal-looking prow to the bulbous, Beluga-like forward quarters of the double-decked Airbus A380 and, well, enough said. As for the tail, where some might see the in-your-face expanse of towering, 62-foot billboard, I see the rakishly canted sail of a tall ship.

Even that name itself — “Seven forty seven” — is such a neat little snippet of palindromic poetry.

Air China 747-8. Author’s photo.

Funny, how we gauge a plane’s commercial success, aesthetic or otherwise: through raw tonnage, wingspan, and this or that statistical bullet-point. Or, in the case of the ubiquitous 737, through the number of units sold. How crass. It’s hard to find romance in the business of aircraft production, but we should take a moment to savor beauty where it exists. “Air does not yield to style,” are words once accredited to an aerodynamicst at Airbus. They, builders of the A380, the graceless behemoth that kicked the 747 into second place on the size list. The ghost of Joe Sutter would like a word with you.

This is also the aircraft that has carried five U.S. Presidents. It carried the Space Shuttle, and, we might note, was perennially the star of any number of Hollywood disaster movies. We should mention its roles in real-life tragedies, too, from the collision at Tenerife, to TWA 800, to the unforgettable photograph of Pan Am’s Maid of the Seas lying sideways in the grass at Lockerbie. Horrific incidents to be sure, but they underscore the 747’s prestige in a way that is almost transcendent — bringing the airplane beyond aviation and into the realm of history proper.

The nature and travel author Barry Lopez once wrote an essay in which, from inside the hull of a 747 freighter, he compares the aircraft to a Gothic cathedral of twelfth-century Europe. “Standing on the main deck,” Lopez writes, “where ‘nave’ meets ‘transept,’ and looking up toward the pilots’ ‘chancel.’ … The machine was magnificent, beautiful, complex as an insoluble murmur of quadratic equations.” Rarely do commercial aviation and spirituality share the same conversation — unless it’s the 747 we’re talking about.

KLM 747-400 at Amsterdam-Schiphol. Author’s photo.

In the second grade, my two favorite toys were both 747s. The first was an inflatable replica, similar to those novelty balloons you buy at parades, with rubbery wings that drooped in such violation of the real thing that I’d tape them into proper position. To a seven-year-old it seemed enormous, like my own personal Macy’s float. The second toy was a plastic model about 12 inches long. Like the balloon, it was decked out in the livery of Pan Am. One side of the fuselage was made of clear polystyrene, through which the entire interior, row by row, could be viewed. I can still picture exactly the blue and red pastels of the tiny chairs.

Also visible, in perfect miniature near the toy plane’s nose, was a blue spiral staircase. Early 747s were outfitted with a set of spiral stairs connecting the main and upper decks — a touch that gave the entranceway a special look and feel. Stepping onto a 747 was like stepping into the lobby of a fancy hotel, or into the grand vestibule of a cruise ship. In 1982, on my inaugural trip on a 747, I beamed at my first real-life glimpse of that winding column. Those stairs have always been in my blood — a genetic helix twisting upward towards some pilot Nirvana.

In the 1990s, Boeing ran a magazine promotion for the 747. It was a two-page, three-panel ad, with a nose-on silhouette against a dusky sunset. “Where/does this/take you?” asked Boeing across the centerfold. Below this dreamy triptych, the text went on:

“A stone monastery in the shadow of a Himalayan peak. A cluster of tents on the sweep of the Serengeti plains. The Boeing 747 was made for places like these. Distant places filled with adventure, romance, and discovery. The 747 is the symbol for air travelers in the hearts and minds of travelers. It is the airplane of far-off countries and cultures. Where will it take you?”

Nothing nailed the plane’s mystique more than that ad. I so related to this syrupy bit of PR that I clipped it from the magazine and kept it in a folder, where it resides to this day. Whenever it seemed my career was going nowhere (which was all the time), I’d pull out the ad and look at it.

Alas, I never did pilot a 747. I’ve been forced to live the thrill vicariously instead, through colleagues who’ve been more fortunate, or by riding along in the cabin or cockpit jump seat. In 1989 I was a passenger on the inaugural 747-400 flight from JFK airport to Tokyo. Everyone on board was given a commemorative wooden sake cup. I still have mine.

For better or worse, however, airlines don’t pick their planes based on beauty or sentimental contemplations, and numbers that made good business sense in 1968 are no longer to the 747’s favor. There’s been a lot of chatter about the plane of late, not much of it auspicious, as the world’s major carriers, one by one, have been sending 747s to the boneyard. Delivery numbers of the final variant, the 747-8 have dwindled to almost nothing, and the assembly line, after almost half a century, is undoubtedly soon to go dark. The fragmentation of long-distance air routes, together with the unbeatable economics of newer aircraft models, have sealed its fate.

When Delta Air Lines retired the last of its 747s in 2017, the plane took a cross-country farewell tour, including a stop at the Washington factory where it was manufactured. At Air France, 300 well-wishers came to Charles de Gaulle airport for a day-long celebration and sightseeing flight over Paris and the French countryside.

The plane’s replacement is not so much the double-decker Airbus A380, as many people assume. The A380 indeed has captured some of the ultra high-capacity market, but with the exception of Emirates’ 100-plus fleet it’s found only in limited numbers. Rather, it’s Boeing’s own 777-300, which can carry almost as may people as a 747, at around two-thirds of the operating costs, that has rendered the four-engine model otherwise obsolete. Pretty much every 777-300 that you see out there — and there are hundreds of them — would have been a 747 in decades past. The -300 has quietly become the premier jumbo jet of the 21st century.

In other cases, market fragmentation has resulted in carriers switching to smaller long-haul planes like the 787 and the Airbus A330. In past decades, traveling internationally meant flying on only a handful of airlines from a small number of gateway cities. Today, dozens of carriers offer nonstop options between cities of all sizes. More people are flying than ever before, but they’re doing so in smaller planes from a far greater number of airports.

With Delta and United having retired the last examples, the 747 is now absent from the passenger fleets of the U.S. major airlines for the first time since 1970. How sad is that? (Atlas Air, that New York-based freight outfit, we turn our lonely eyes to you.)

Just the same, reports of the plane’s death have been exaggerated. Hundreds remain in service worldwide: British Airways, Lufthansa, Korean Air and KLM have dozens apiece, in both freighter and passenger configurations. Other liveries, too, can be spotted at airports both at home and overseas: Virgin Atlantic, Air China, Qantas. While the 747-8 has sold only sporadically, there are enough of them around to ensure they’ll be crossing oceans for years to come.

Icon is such an overused term in our cultural lexicon, but in the case of the 747, it couldn’t be more apt. Like other American icons of design and commerce, from the Empire State Building to the Golden Gate Bridge, it endures — a little past its prime, perhaps, but undiminished in its powers to inspire and awe. And this one literally flies, having carried tens of millions of people to every corner of the globe — an ambassador of determination, technological know-how, and imagination at its best.

It could be a metaphor for American itself: no longer the most acclaimed or the flashiest, it remains stubbornly dignified, graceful and important in ways you might not expect. And in spite of any proclamations of its demise, it carries on.

747 at Kennedy Airport, 1997. Author’s photo.

Now for some fun:

The picture at the top of this article shows the prototype Boeing 747 on the day of its rollout from the factory in Everett. It was September 30th, 1968. I love this photo because it so perfectly demonstrates both the size and the grace of the 747. It’s hard for a photograph to properly capture both of those aspects of the famous jet, and this image does it better than any I’ve ever seen.

Across the forward fuselage you can see the logos of the 747’s original customers. The one furthest forward, of course, is the blue and white globe of Pan Am. Pan Am and the 747 are all but synonymous, their respective histories (and tragedies) forever intertwined. But plenty of other carriers were part of the plane’s early story, as those decals attest. Twenty-seven airlines initially signed up for the jumbo jet when Boeing announced production.

My question is, can you name them? How many of those logos can you identify?

Here, and here, are a couple of closer-in, higher resolution shots to help you.

Once you’re ready, scroll down for the answers.

The 747 in those archival Boeing photos still exists, by the way, and you can visit it — touch it — at the Museum of Flight at Seattle’s Boeing Field.

And the answers are…

Here are the 27 original customers. You may wish to reference this close-up photo as you go along, left to right…

Top row:

Delta Air Lines

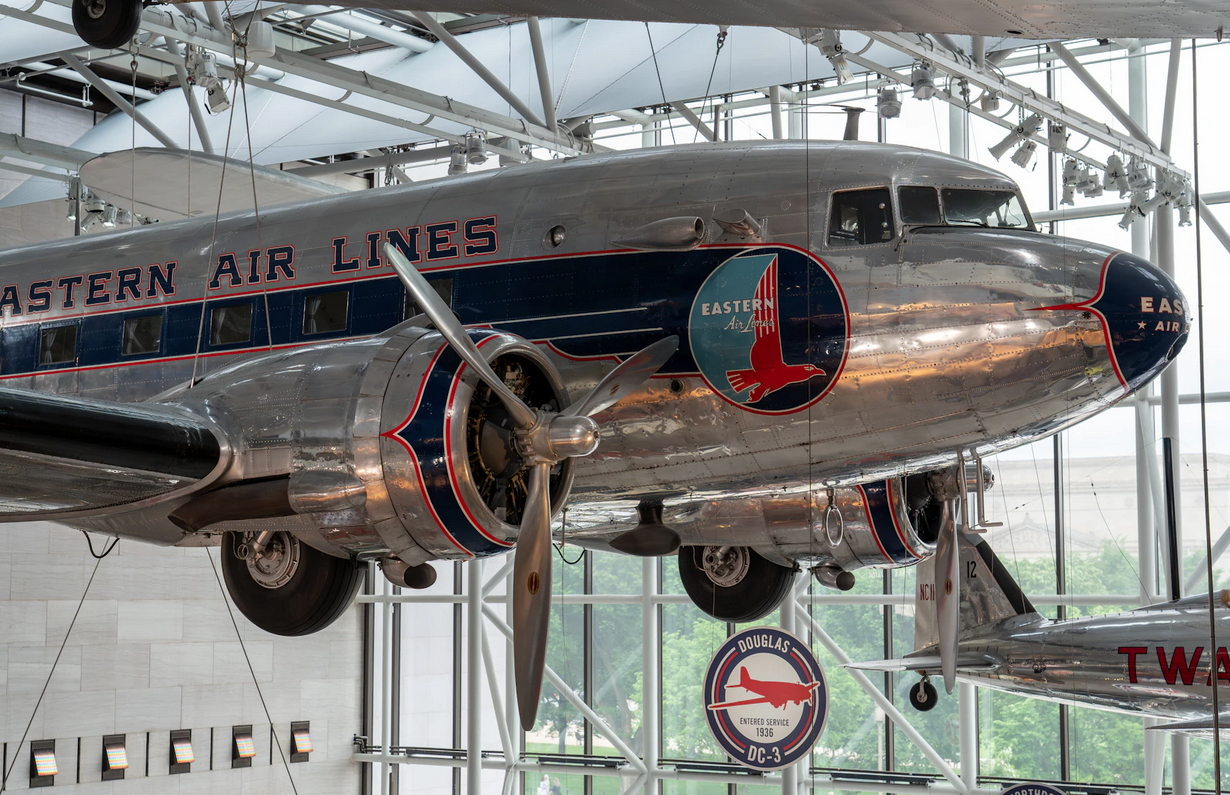

Eastern Airlines

Air India

National Airlines

World Airways

United Airlines

American Airlines

Air France

BOAC

Lufthansa

Bottom row:

Sabena

Iberia

South African Airways

Air Canada

El Al

Braniff International

Scandinavian Airlines (SAS)

Swissair

Qantas

KLM

Aer Lingus

Alitalia

Northwest Airlines

Continental Airlines

Trans World Airlines (TWA)

Japan Airlines (JAL)

Pan American

Twenty-seven carriers got things rolling, though many more would follow, from Cathay Pacific to Air Gabon. I’m not sure of the meaning of the order of the decals. Pan Am was the launch customer, and its logo is located furthest forward — either first or last on the list, depending how you see it. The rest may or may not be chronologically arranged, I don’t know.

Whatever order they are in, there’s a tremendous amount of history in those logos. Let’s take a quick look at each of the 27 carriers, and their trademarks. Again, left to right, top row first:

1. Delta operated only a handful of the original 747-100, and not for very long, although later it would inherit more than 20 of the -400 variant through its merger with Northwest. The last of those jets was retired last year. The Delta “widget” symbol is today a two-tone red, but is otherwise identical to the mark you see in these photos.

2. A single 747-100 flew in Eastern colors only very briefly before it was sold to TWA. The airline’s blue and white oval, however — one of the most iconic airline trademarks of all time — endured a lot longer. This was the final incarnation of the carrier’s longtime falcon motif, and Eastern used it right to the end, until the company’s demise at the hands of Frank Lorenzo in 1991.

3. Air India operated four different 747 variants before switching to the 777-300. The centaur logo, representative of Sagittarius, suggested movement and strength. It also resembled the farohar, a Parsi heavenly symbol featuring a winged man. The Parsis are a Zoroastrian sect of the Subcontinent — of which Air India’s founding family, the Tatas, were members — and their farohar is a sign of good luck. Sadly, the carrier abandoned this culturally rich trademark some years ago.

4. National Airlines flew the 747 on routes between the Northeast and Florida. In 1980 the airline merged with Pan Am. Its “Sundrome” terminal at Kennedy Airport, where the JetBlue terminal sits today, was designed by I.M. Pei.

5. World Airways was a U.S. supplemental carrier that flew passenger and cargo charters worldwide for 66 years until ceasing operations in 2014. It operated the 747-100, -200 and -400.

6. Until last year, United Airlines had operated the 747 without interruption since 1970, having flown the -100, -200 and -400 variants, as well as the short-bodied SP version. The latter were inherited from Pan Am after purchase of that airline’s Pacific routes in 1986.

7. American Airlines sold the last of its 747s more than two decades ago, but over the years its fleet included the -100 and, for a short period, the SP. The emblem in the photos shows an early version of the famous AA eagle logo, later perfected by the Italian designer Massimo Vignelli and worn by the carrier until its disastrous livery overhaul in 2013.

8. The Air France seahorse logo still graces the caps of the airline’s pilots. Air France flew the 747-100, -200, and -400. Today, the 777-300 and A380 do the heavy lifting.

9. BOAC, the British Overseas Airways Corporation, merged with British European Airways in 1974 to form what today is known as British Airways. That black, delta-winged logo traces its origins to Imperial Airways in the 1920s. Known as the “Speedbird,” this is where British Airways’ air traffic control call-sign comes from.

10. Lufthansa’s crane logo, one of commercial aviation’s most familiar symbols, is mostly unchanged to this day. The airline’s 13 747-400s and 19 747-8s comprise what is, at the moment, the largest 747 fleet in the world. The -100 and -200 were in service previously, including a freighter version of the -200.

11. Sabena, the former Belgian national carrier, flew the 747-100, -200 and -300. The airline ceased operations in 2002 after 78 years of service. This logo is one of the hardest to identify in the Boeing photos. It’s blurry in most pictures, and the carrier didn’t use it for very long. People are much more familiar with Sabena’s circular blue “S” logo.

12. Spanish carrier Iberia flew 747s for three decades, but today it relies on the A330 and A340 for long-haul routes. Different versions of the globe logo were used until the late 1970s.

13. South African Airways is among the few airlines to have flown at least four different 747 variants: the -200 through -400, plus the SP. The springbok, an African antelope, remained its trademark until a post-Apartheid makeover in the 1990s.

14. Air Canada recently brought back the five-pointed maple leaf as part of a beautiful new livery. Alas, you won’t be seeing it on a 747. The last one left the fleet in 2004.

15. El Al is Hebrew for “to the skies,” and the Israeli airline still operates a handful of 747-400s mainly on flights between Tel Aviv and New York.

16. It was hard to miss one of Braniff’s 747s. The Dallas-based carrier, one of America’s biggest airlines until it was killed off by the effects of over-expansion and deregulation, painted them bright orange.

17. Each of Scandinavian’s 747s carried a “Viking” name on its nose — the Knut Viking, the Magnus Viking, the Ivar Viking among them — with a fuselage stripe that soared rakishly upward into the shape of a longboat. Just a beautiful plane, as you can see below. That striping is long gone, but the SAS trademark, one of the most enduring in aviation, is unchanged.

18. After being in business for 71 years, Swissair closed down forever in March, 2002. It had flown the 747 -200 and -300.

19. Qantas — that’s an acronym, by the way, for Queensland and Northern Territory Aerial Services — uses a modernized version of this kangaroo logo, and continues to operate a fleet of a dozen or so 747-400s.

20. KLM is the world’s oldest airline, and this logo, a masterpiece of simplicity, is still in use today, only barely altered. There are 17 747s in the KLM fleet. With United out of the picture, KLM joins Lufthansa, Qantas, El Al and BOAC/British Airways as the only members of the original 27 to have operated the jet continuously since 1970.

21. Aer Lingus 747s were a daily sight here in Boston throughout the 1970s and 1980s, before the airline downsized to the Airbus A330. A modernized shamrock logo remains on the tail.

22. Alitalia’s “Freccia Alata” bow and arrow is the emblem that readers had the most trouble with. This was the airline’s symbol until 1972, before changing to the stylized red and green “A” used to the present day. It looks even older than it is. One emailer described it wonderfully as, “something Gatsby would have on cufflinks.” Alitalia parted ways with the 747 in 2002, switching to the 777 and A330.

23. Northwest, which merged with Delta in 2008, was for a time the world’s largest 747 operator, with more than 40 in service. It was the launch customer of the 747-400 in 1989. The last of those planes, now wearing Delta colors, will be flown to the desert later this month, ending 47 years of 747 passenger service by U.S. carriers.

24. Continental Airlines flew the 747-100 and -200 on and off, but never had more than a handful. The “meatball” logo, as some people callously called it, was designed by Saul Bass and used from 1968 until 1991. Continental merged with United in 2010.

25. TWA, one of the world’s most storied carriers, was an early 747 customer and kept the type in service until 1998 — shortly after the flight 800 disaster. Though few people remember it, TWA also had a small fleet of three 747SPs at one point. The SP paint job included the markings “Boston Express,” as they were primarily used on routes from Boston to London and Paris.

26. Japan Airlines flew more 747s than anybody — at one point over 60 — including a high-density short-range version that held 563 passengers! (It was one of those “SR” planes that crashed near Mt. Fuji in 1985, in what remains the deadliest single-plane accident of all time.) JAL’s crane logo, with the bird’s wings forming the shape of the Japanese rising sun, is the most elegant airline logo ever created. JAL retired the crane in 2002 as part of a monstrously ugly redesign, but wisely brought it back nine years later.

27. And then there’s Pan Am — the blue globe that was once as widely recognized as the logos of Coca-Cola or Apple. What can you say?

Related Story:

WE GAAN. THE HORROR AND ABSURDITY OF HISTORY’S WORST AIR DISASTER

Joe Sutter and factory photos courtesy of Boeing.