Express Blog

Ask the Pilot Express is a Semi-Daily Mini-Blog Featuring News Blurbs, Photos, Updates, Random Musings and More.

Subscribe to the EXPRESS RSS

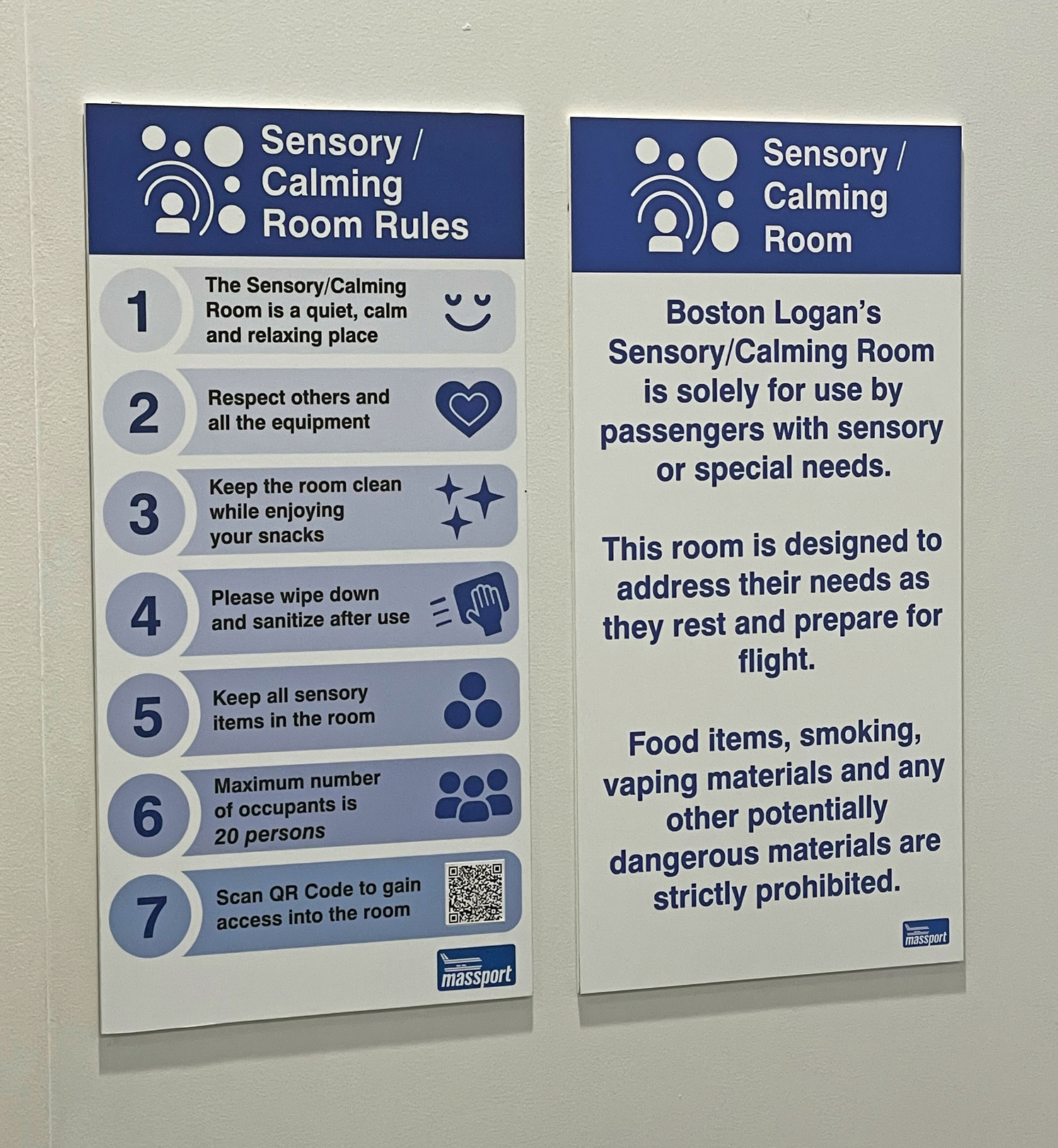

December 10, 2024. A Quiet Place.

I found this the other night at Boston-Logan, over at terminal E.

I didn’t peek inside; all the signage and rules felt a bit intimidating and excessive (and counterintuitive to the whole idea). Alas, I cannot report back on what “sensory items” might entail, or why they need to be wiped down and sanitized.

The concept is a welcome one, but the point I wish to make is that rooms like this might not be necessary if airports would only learn to dial down the PA speakers and make themselves quieter and more relaxing. If you’re a regular reader, you know of my disdain for the microphone-induced racket that plagues our terminals. Passengers shouldn’t have to seek out some novelty hideaway space just to find peace and quiet.

Related Story:

TERMINAL RACKET: THE SCOURGE OF AIRPORT NOISE.

November 14, 2024. LGA Reborn.

Well there’s a sign you never dreamed you’d see. But there it is, and it’s not without merit.

The main terminals at La Guardia Airport have been completely rebuilt, and the results, at least by U.S. airport standards, are stunning. The lobbies and concourses are handsome, spacious, (relatively) quiet, and flooded with natural light. This is not the La Guardia we knew for all too long. I spent some time there a week or so ago, walking around and checking things out. I hadn’t been to the airport in ages, and I could hardly believe my eyes when I stepped off the plane.

The only thing missing is an efficient public transport link into Manhattan. Should it ever get done, LGA will have completed what might be the most spectacular transformation of any major airport in the world.

October 9, 2024. Des Couleurs Magnifique.

Apropos of nothing, a shout-out to Air France for the longevity of its paint scheme. It’s donwright impressive how long the airline has worn its current livery. As well it should; it’s one of the industry’s best.

Back in the late 1970s, Air France was one of the first major carriers to ditch the horizontal “cheat line” striping and move to what aviation nerds call the “Eurowhite” look. And for more than four decades it’s served them well.

There have been minor changes over the years. The tail stripes have been softened, and, most recently, the typeface was revised and now spells the compound “AIRFRANCE.” But the template overall has stayed the same. I can think of no other airline whose colors have been so consistent.

The circular logo near the cockpit (see upper photo) is called the Hippocampe Ailé, and it dates to the 1930s, featuring a Pegasus head with the tail of a mythical sea dragon. We’re glad Air France hasn’t ditched this emblem, deeming it too anachronistic or some such. On the contrary, they’ve enlarged it and moved it to the front.

Photos by the author.

September 12, 2024. DC-10 Demise.

For ten years, La Tante, a restaurant set inside a disused McDonnell Douglas DC-10, was a popular landmark just outside the airport in Accra, Ghana. I had lunch there once and wrote of the experience here.

Well, a few weeks ago I was touching down in Accra and noticed a conglomeration of aircraft parts stacked near the perimeter fence: segments of a fuselage, pieces of a wing, a tail. I suddenly realized these were the remains of La Tante. The restaurant has closed and been dismantled.

I tried getting a photo from the crew van, but we weren’t in a good spot. Which is just as well; it was sad seeing the restaurant broken apart. Better to remember it in happier, tastier times.

The spot where it stood has been cleared and looks eager for repurposing — no doubt into something boring, like an office park or retail space.

Related Story:

THE WORLD’S COOLEST RESTAURANT

September 4, 2024. Let’s Be Frank.

So the Wall Street Journal ran an op-ed by Frank Lorenzo, of all people, pushing back against government efforts to rein in airline fees and impose new regulations. If you’re not sure who Frank Lorenzo is, look him up. As a friend of mine put it, Lorenzo opining about the airlines is akin to Hannibal Lecter giving advice on fine dining.

That said, Lorenzo’s complaints aren’t wrong, exactly. The type of bureaucratic meddling being proposed could end up hurting consumers more than it might help. But he and the Transportation Department, run by Pete Buttigieg, are fussing over minutiae rather than addressing what’s really wrong with flying. The problem isn’t lavatory accessibility or the speediness of refunds. The problems are congested skies, an understaffed air traffic control system, and tedious airport security.

Long lines and long delays, in other words. Fix those two things, and you’ve made commercial air travel a vastly more pleasant experience: Rethink TSA, fund ATC, and incentivize airlines to consolidate departures in the most crowded sectors, using larger planes. Then you can fuss over the small stuff.

Photo courtesy of Unpslash.

August 28, 2024. Sticker Shock.

The COVID-19 disaster is not anything I want or need to be reminded of. But vestiges are still everywhere. This photo was taken in a jet bridge at the Honolulu airport a few weeks ago.

Back during the height of the pandemic, the permanent-ness of these stickers, brand-new at the time, was pretty apparent. Clearly they were intended to last, and that worried me. No one was paying any mind, it seemed, to the idea that things like “social distancing” might only be temporary — to the notion that we could be normal again. It was scary.

I’m unsure at what point during that stretch we hit peak insanity. It may have been the moment in 2021 when I was flying from Bogota to Santa Marta, in Colombia. (I managed to take two or three vacations during the pandemic, and this was one of them.) After takeoff, the LATAM crew made the following announcement:

“In accordance with the directives of the Colombian health ministry, we have eliminated onboard service. Due to the risk of saliva droplets, we also ask that passengers remain silent for the duration of the flight. Please refrain from speaking or laughing.”

August 19, 2024. Tall Tail.

Any doubt that Atlas Air, the New York-based cargo airline, has the handsomest tail in all of commercial aviation?

Atlas himself hoisting the world on his shoulders. It’s an apropos motif for a freight carrier, and just an all-around fantastic design: bold, elegant, unmistakable without being too showy. Compare the segmented globe with United’s ugly variant. No contest.

Photo courtesy of Itamar Reuven.

August 12, 2024. Midsummer Morbid.

The Japan Airlines “Tsurumaru” logo is, to me, the most elegant airline logo of all time. Created in 1958 by an American ad firm, it is still used by JAL. The emblem features a crane — the symbol of fortune and longevity in Japan — lifting its wings into the circular suggestion of the Rising Sun.

Regrettably, today marks the 39th anniversary of one of the darkest days in aviation history — the crash of JAL flight 123. On August 12th, 1985, the Boeing 747 crashed into the mountains near Tokyo killing 520 people. It remains the second-deadliest air disaster ever, and the deadliest involving a single aircraft.

Twelve minutes after takeoff from Tokyo’s Haneda Airport, flight 123’s aft pressure bulkhead burst, causing a rapid decompression. Air rushed up into the into the plane’s tail structure with such force that it ripped off a section of the fin and caused a total loss of hydraulics. Out of control, the plane went down twenty minutes later, slamming into a pair of ridges near Mount Osutaka and disintegrating.

The airplane was a short-range, high-capacity variant of the 747-200 called the SR (short range), built specifically for the Japanese domestic market. This accounts for the incredibly high death toll.

Despite how destructive the impact was, four people, all of them seated in the very rear of the cabin, remarkably survived. The accident occurred at twilight, and search teams weren’t mobilized until the following day; according to the four who were rescued, others had survived the crash as well, only to perish during the night.

Later, when investigators developed film found in cameras belonging to the victims, they discovered photographs taken from inside the cabin. The saddest of these, shot through a starboard window before things went wrong, shows the airplane’s wing approaching the coastline at sunset. In another, taken just minutes later, a flight attendant stands in the aisle cupping an oxygen mask to her face. Also unearthed form the wreckage were several farewell notes scribbled into notebooks and on pieces of paper.

Google will show you those pictures. Even more chilling is the cockpit voice recording, where you can hear the pilots fighting for their lives, using only engine thrust for control.

The cause of the accident was traced to a faulty repair made to the aft pressure bulkhead seven years earlier, after an unusually hard landing. Japan Airlines, long-respected for reliability and safety, fell into a period of disgrace. Yasumoto Takagi, the airlines president at the time, resigned after visiting families of the victims to apologize in person. A JAL maintenance manager, as well as the engineer who had inspected the plane prior to its final flight, committed suicide.

And what a year that was, 1985. Nowadays, large-scale air disasters have become so rare that even one or two over the course of a year is unusual. Back in ’85, the JAL debacle was one of twenty-seven — that’s correct, twenty-seven — serious accidents to occur that year, in which nearly 2,500 people were killed. Among the others were the Arrow Air crash in Newfoundland that killed 240 American servicemen, and, less than two months before JAL 123, the Air-India bombing over the North Atlantic that left 329 dead. It’s hard to fathom, but two of history’s ten worst air disasters happened within fifty days of each other.

For all of the convulsions the airlines are going through at the moment, perhaps we can savor one positive: they don’t do crashes like they used to.

May 6, 2024. Dlaczego nie Polska?

I was flipping through the Polish translation of my book (the latest edition has been oddly popular in that country for some reason), marveling at the Polish language’s impenetrable salad of consonants. And something struck me: no U.S. carrier flies to Poland.

Nor has any American carrier flown to Poland since Delta in the 1990s, after Delta took over Pan Am’s European network — and I’m pretty sure they did it only from Frankfurt or Berlin, not as a direct flight from the States. American Airlines did announce a Chicago-Warsaw route just before COVID hit, then scrapped it and never re-announced it.

Why? This isn’t a trick question. I don’t know the answer. And it seems odd. Not only are there millions of Polish-Americans, but the largest community of Polish-Americans lives in and around Chicago, a major hub for both American Airlines and United. Polish carrier LOT, meanwhile (one of the oldest airlines in the world, established in 1928), has flown to both O’Hare and JFK for decades. Is it a political thing? Is there simply not enough premium fare traffic to warrant such a route?

A LOT Boeing 787 at New York’s JFK Airport.

The Israeli carrier El Al sometimes operates charters from JFK to the Polish city of Katowice. My guess is that these are remembrance tours of some kind, as the Auschwitz-Birkenau site is nearby to there.

While were at it, what other “missing routes” can you think of? Can you name another city-pair that seemingly should have airline service, but for whatever reasons does not?

April 16, 2024. High Cuisine.

We all know airport prices can be ridiculous, but where’s the limit?

Here are a couple of delectables to set you back. The first is from Legal Sea Foods at Logan Airport in Boston. The second is from a sandwich place at LAX called Homeboy.

PHOTOS BY THE AUTHOR

April 6, 2024. R.I.P. Air Malta

Another old world carrier has bitten the dust. This time it’s Air Malta, national carrier of its namesake island nation.

Air Malta had been around since 1974, and once flew Boeing 720s across Europe (Google that one if you need to). The company had been floundering for some time, under heavy pressure from low-cost leisure carriers, and shut its doors for good on March 30th.

In its place, taking on most of Air Malta’s Airbus A320s, is a government-run entity called KM Malta Airlines, whatever that means. There’s also a low-cost outfit called Malta Air, in case the name thing isn’t confusing enough.

I don’t like it when flag carriers — to use a vintage expression — go out of business. See Swissair, Sabena, et al. Each time it happens, commercial aviation loses a little more history and dignity, while dumb-named LCCs and startups flood the field.

In 2015 I flew aboard Air Malta, and wrote about the experience in a piece titled, “Long Live Air Malta!”

I did what I could.

March 27, 2024. Tenerife Remembered.

Just a reminder, morbid as it might be, that today marks the 47th anniversary of the deadliest aviation disaster of all time.

On March 27th, 1977, on the Spanish island of Tenerife, two Boeing 747s collided on a foggy runway, killing 583 people. There’s a surreal, almost mythical aura that surrounds the accident, due in no small part to the almost unbelievable cascade of ironies and coincidences that led to it — beginning with the fact that neither plane was supposed to be at Tenerife in the first place.

I was only ten years old, but I clearly remember the day it happened, watching the news in our downstairs living room — the choppy, black-and-white footage from a place I’d never heard of.

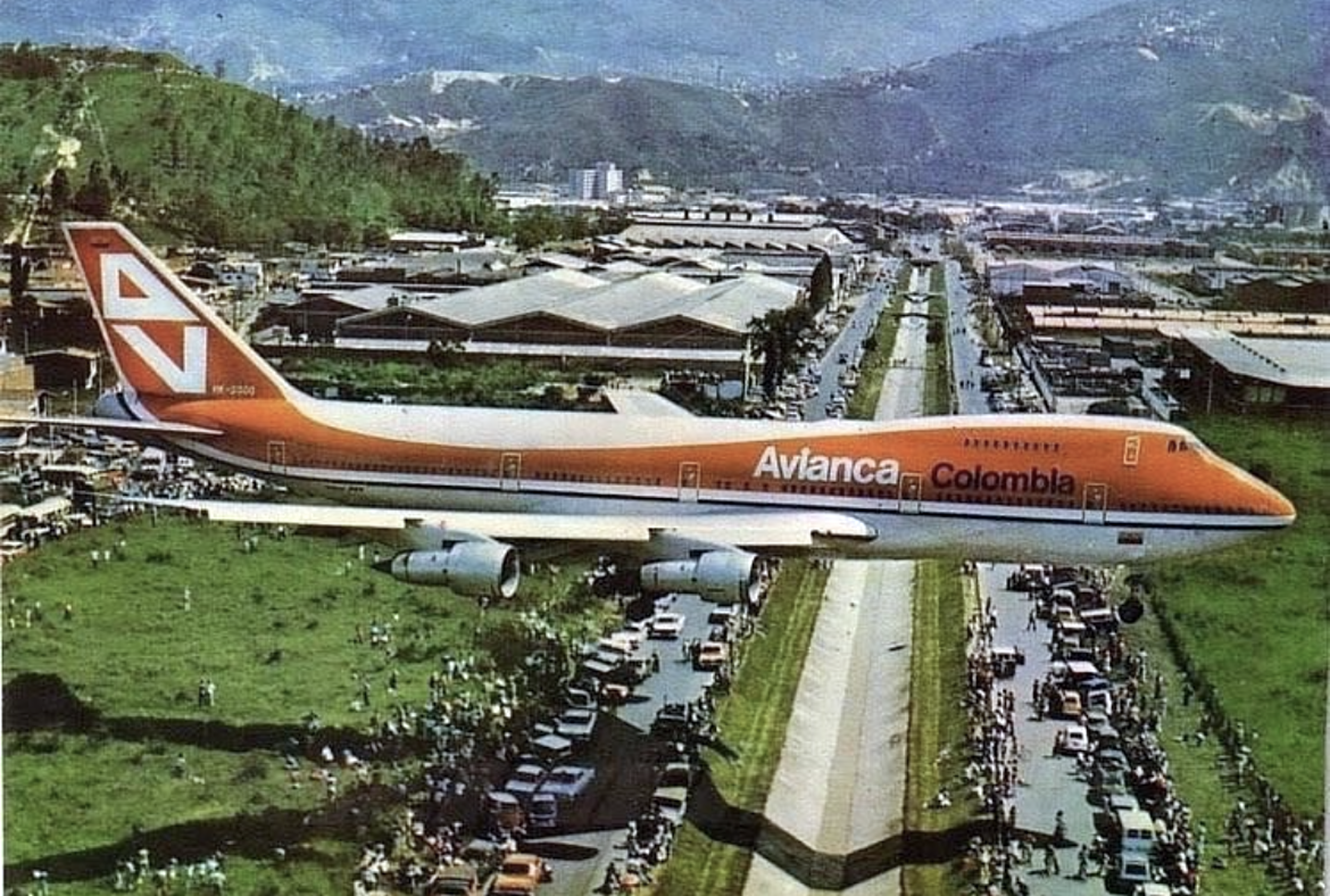

March 17, 2024. Crowd Pleasers.

I have this old Avianca Airlines postcard from the 1970s. You can see it above. It’s a picture of the first Boeing 747 to land at Medellin, Colobmbia. What makes the photo so striking are the spectators crowding the roadway at the edge of the airport — a great jumble of cars and people. Hundreds showed up to watch the jet come in.

On Instagram I discovered a similar photo of the first 747 to land in Japan. The caption says that ten thousand people jammed the observation decks at Haneda Airport for the occasion.

And so on. You can find any number of pics like these.

Imagine, today, ten thousand people making their way to an airport just to look at an airplane. It wouldn’t happen, of course. Not even the A380, when it made its debut, got anywhere close to the attention of the Comet, the 747 or the Concorde.

As maybe we should expect. So goes the evolution of technology, no? Jetliners were once a novelty; they aren’t any more. Not even the biggest ones.

Still, we’ve lost something. Beautiful machines that carry hundreds of people around the world at tremendous speeds, and it’s nothing to us. What a strange thing to take for granted.

Photo: Avianca Airlines, from the author’s postcard collection.

February 2, 2024. Slippers.

There’s a lot going on in the airline world: the 737 saga, the blocking JetBlue’s merger with Spirit. Allow me to ignore these stories and talk about something more exciting: airplane slippers.

You know how it goes. You’re on a long-haul trip in first or business, and they give you a pair of those slippers. They’re flimsy and flat on the bottom; you can feel the cardboard insert that forms the sole. After ten minutes, one of them falls off. A few minutes later the other one goes. Later you find them on the floor, lodged somewhere in the footwell. Sometimes, you’re on the way to the lav and the damn things slip off in mid-stride.

We don’t expect carriers to spend much on single-use amenities, but the sad design of the typical inflight slipper makes a cheap and wasteful product only more cheap and wasteful.

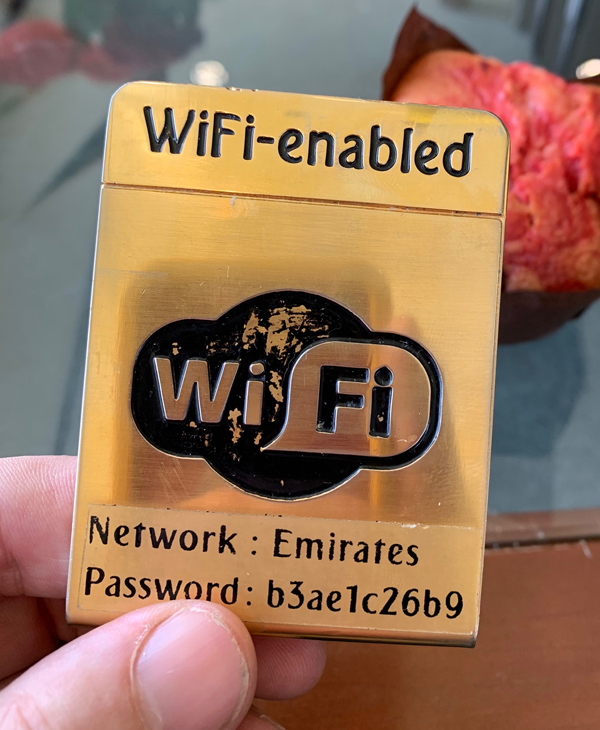

One airline has, at last, addressed this. Imagine my delight when I slipped on these new first class Emirates slippers and discovered they include an elastic band that attaches around the heel. A simple, elegant, and (I would guess) inexpensive fix…

How much fun.

Now you can jog your way to the bathroom without a slip; kick your legs around as you toss and turn in your suite; wiggle your toes and shake your ankles. These things stay on.

I swear, this is the smartest thing to happen to premium class air travel in years.

Best of all, you can bring them home and reuse them. They’re still cheap slippers, but they’re good enough to wear into the basement when I have to switch the clothes from the washer to the dryer, or out to the porch for my Amazon packages.

Sometimes it’s the little things.

And this guy could use a pair…

Photos by the author.

January 17, 2024. Desert Desecration.

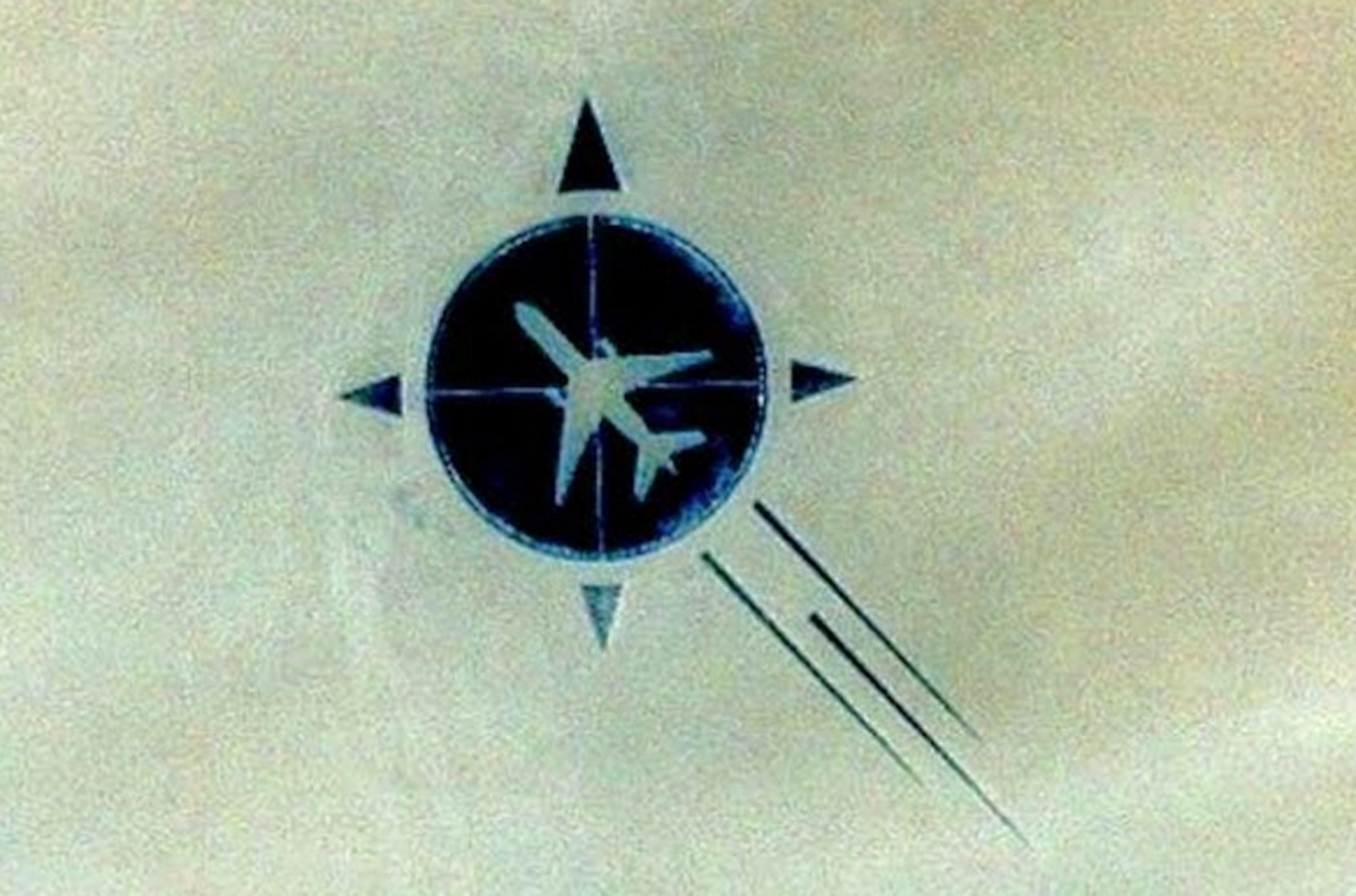

In a post from a couple of weeks ago, I mentioned the fascinating memorial erected in the Sahara Desert honoring the victims of UTA flight 772, which was bombed in 1989. It was constructed in 2007 in the spot where the plane fell, in the Tenere region of central Niger, paid for using some of the $170 million compensation provided by the Libyan government, which carried out the bombing.

Any number of crash memorials are scattered around the world, and this is maybe the most haunting and evocative of them all. It was built using desert stones, mirrors, and pieces of the wreckage itself, backdropped by one of the most remote and inhospitable landscapes on earth.

It forms a compass rose, with the silhouette of a jet traveling northwesterly — the direction the DC-10 was headed, en route to Paris, when a luggage bomb destroyed it.

Well, I just learned from a reader that the monument was recently vandalized and badly damaged. Nobody knows for sure who did it, but it’s likely the incident is related to last summer’s coup in Niger and the anti-French sentiments percolating within the country.

This is sad to say the least. Desecrating a memorial to the victims of mass murder seems in especially bad taste, and many of flight 772’s passengers were African, not French.

Screen grab from Google Earth

January 2, 2024. Haneda Collision.

UPDATED on JANUARY 5th

Early last Tuesday evening, a Japan Airlines Airbus A350 collided with a Japanese coast guard plane while landing at Tokyo’s Haneda Airport. Most of you have seen the ghastly footage for the A350 skidding down the runway in flames after striking the much smaller de Havilland Dash-8 turboprop. Five people on the smaller plane were killed.

What went wrong, and who’s to blame, will be deciphered in time. For now, the most noteworthy and remarkable thing is that all 379 passengers and crew aboard the JAL plane were evacuated safely. This could have been much, much worse.

And it’s yet another example of why you should never, ever, fuss around with your carry-on luggage during an evacuation. When a plane is ablaze, the difference between life and death — yours or someone behind you — can be a matter of seconds. As we’ve seen in a number of evacuations in recent years, too may people insist on evacuating with their belongings, blocking up the aisles and wasting precious time.

I don’t care what contraband or sex toys you’ve got tucked away in your roll-aboard, or what valuable business secrets are on your company laptop: get the fuck out of the plane and leave your bags behind.

Reportedly, the first PA made to passengers as the JAL jetliner scraped to its fiery stop, was a stern warning to ignore any luggage and get to the exit slides immediately. Well done.

Mostly. One big asterisk is the time it took to get everyone off the plane. The FAA expects a jetliner to be fully evacuated within 90 seconds, even with half of its doors blocked or inoperative. It took over ten minutes for the JAL plane to be fully vacated.

Why it took so long is unclear, and will need to be scrutinized carefully. Was it a lack of urgency? Confusion? Whatever the reasons, it’s unacceptable. and our evacuation protocols may need some revising.

December 27, 2023. Czech Centennial.

I’m a couple of months late with this, but congratulations to CSA, the flag carrier of the Czech Republic, for celebrating its 100th birthday in October.

Albeit barely. Once a mainstay carrier of Central Europe, with a network reaching the United States, CSA is down to only two airplanes and a handful of destinations. The company survived a 2021 bankruptcy filing, but its future is at best uncertain. Maybe that hideous livery has something to do with it.

Nonetheless, they’ve survived a hundred years, joining KLM, Avianca, Aeroflot and Qantas as the only carriers to hit the century mark. Let’s hope they keep going.

In the days before that atrocious paintjob you see above, the words “OK Jet” emblazoned the tails of CSA’s planes. “OK” is the airline’s two-letter IATA code, and also the aircraft registration prefix of the Czech Republic and former Czechoslovakia. Incorporating this into a tail emblem was equal parts peculiar and charming. The Cold War was maybe more fun than we remember.

Top photo courtesy of Ondrej Bocek and Unsplash.

Lower photo from the author’s postcard collection.

December 21, 2023. Lockerbie at 35

Today, December 21st, is the winter solstice and either the shortest or longest day of the year, depending on your hemisphere. It also marks the 35th anniversary of one of the most notorious terrorist bombings — the 1988 downing of Pan Am flight 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland.

Flight 103, a Boeing 747 named Clipper Maid of Seas, was bound from London to New York, when it blew up in the evening sky about a half-hour after takeoff. All 259 passengers and crew were killed, along with eleven people on the ground in Lockerbie, where an entire neighborhood was virtually demolished. Debris was scattered for miles.

Until 2001, this was the deadliest-ever terror attack against American civilians. A photograph of the decapitated cockpit and first class section of the 747, lying crushed on its side in a field, became an icon of the disaster, and is perhaps the saddest air crash photo of all time.

Two Libyans, Abdelbaset al-Megrahi and Lamin Khalifah Fhimah, were later tried in the Netherlands for the bombing. Fhimah was acquitted, but al-Megrahi was convicted and sentenced to life. The alleged bomb maker, Abu Agila Mohammad Mas’ud Kheir Al-Marimi, was apprehended in December, 2022, and awaits trial.

The government of Mohammar Khaddafy would also be held responsible for the 1989 destruction of UTA flight 772, a DC-10 bound from Congo to Paris. Few Americans remember this incident, but it has never been forgotten in France (UTA, a globe-spanning carrier based in Paris, was eventually absorbed by Air France). A hundred and seventy people were killed when an explosive device went off in the forward luggage hold.

The wreckage fell into the Tenere region of the Sahara, in northern Niger, one of the planet’s most remote areas. (Years later, a remarkable memorial, incorporating a section of the plane’s wing, was constructed in the desert where the wreckage landed.)

Khaddafy eventually agreed to blood money settlements for Libya’s hand in both attacks. The UTA agreement doled out a million dollars to each of the families of the 170 victims. More than $2.7 billion was allotted to the Lockerbie next of kin.

The investigation into the Lockerbie bombing was one of the most fascinating and intensive in history. The U.S. prosecutorial team was led by a hard-nosed assistant attorney general named Robert Mueller (yes, that Robert Mueller). Much of the footwork took place on the Mediterranean island of Malta, where the explosive device, hidden inside a Toshiba radio and packed into a suitcase, was assembled and sent on its way. The deadly suitcase traveled first from Malta to Frankfurt, and from there onward to London.

Both Abdelbaset al-Megrahi and Lamin Khalifah Fhimah had been employees of Libyan Arab Airlines, and Fhimah was the station manager there in Malta. During my vacation to the island a couple of years ago, it was a little eerie when I found myself walking past the Libyan Airlines ticket office, which is still there, just inside the gate to the old city of Valletta.

In 2009, in a move that has startled the world, Scottish authorities struck a deal with the Libyan government, and al-Megrahi, terminally ill at the time, was allowed to return home, to be with his family in his final days. He was welcomed back as a hero by many.

There’s lots to read online about flight 103, including many ghastly day-after pictures from Lockerbie. But instead of focusing on the gorier aspects, check out the amazing story of Ken Dornstein, whose brother perished at Lockerbie, and his dogged pursuit of what really happened. (Dornstein, like me, is a resident of Somerville, Massachusetts, and he lives within walking distance.)

Upper photo courtesy of Pan Am Museum.

Second photo by the author.

November 29, 2023. Logan Lament.

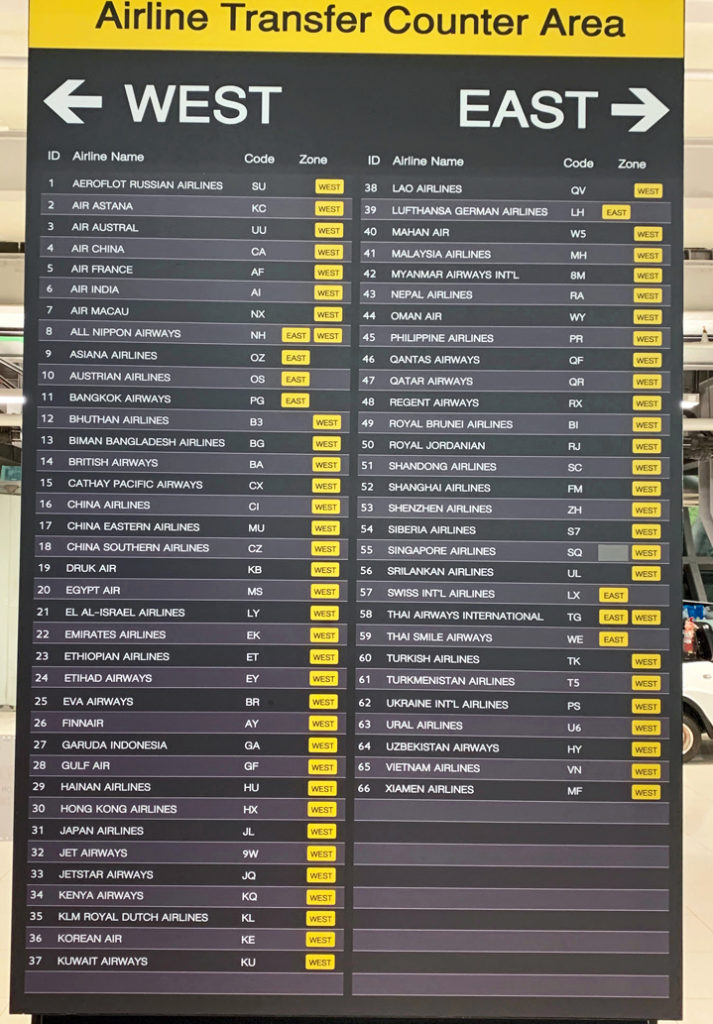

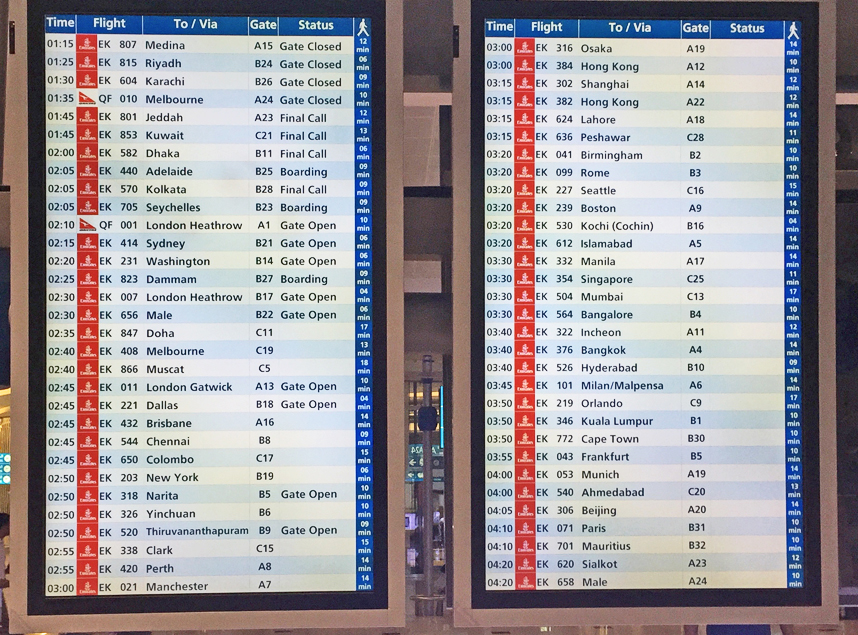

Over the last ten or twelve years, no U.S. airport that has seen more long-haul growth than my hometown airport, Boston’s Logan International. Not that long ago, we had a handful of European routes, some service to the Caribbean, and that’s about it.

How things have changed. Today you can fly nonstop from Boston to Europe, Asia, South America and the Middle East. Pretty much all of the big global players are here, from Emirates to Turkish to Korean. Delta alone has direct flights to nine transatlantic cities, with more planned.

The downside to all of this expansion has been overcrowding and a lack of gates. The only terminal with Customs and Immigration facilities is terminal E, which until recently had fewer than a dozen jet bridges. At the height of summer crowds were unbearable, and long delays were common as planes had to be jockeyed back and forth between the gates and remote parking stands.

And so, when ground was broken for a badly needed terminal E expansion, many of us were excited.

Well, that project is now complete, and I’m sad to say I’m a little underwhelmed. Or confused at any rate. After many months and hundreds of millions of dollars, what we got is only four additional gates.

The new superstructure is enormous. The addition alone is nearly the length of the original building (which, itself, was significantly expanded about twenty years ago). This I imagine — or, I hope — will go a long way towards thinning out those evening departure crowds.

That’s great, but only four gates? With airlines planning more new flights as we speak (just this week Hainan Airlines relaunched its suspended Boston-Beijing service), how much of terminal E’s parking snarl is this going to relieve, exactly?

And no expansion to the Immigration lobby? When I was there a few weeks ago the passport lines were two hours long.

What am I missing? Hopefully this isn’t the usual Boston boondoggle: lots of expensive construction for not a lot of fix.

And, yes, the new extension is very… red. It looks like a spaceship, or the fender of an vintage sports car; retro and futuristic at the same time. It really gives the airport some flair, and I quite like it. I just wish it came with more gates.

Photo by the author.

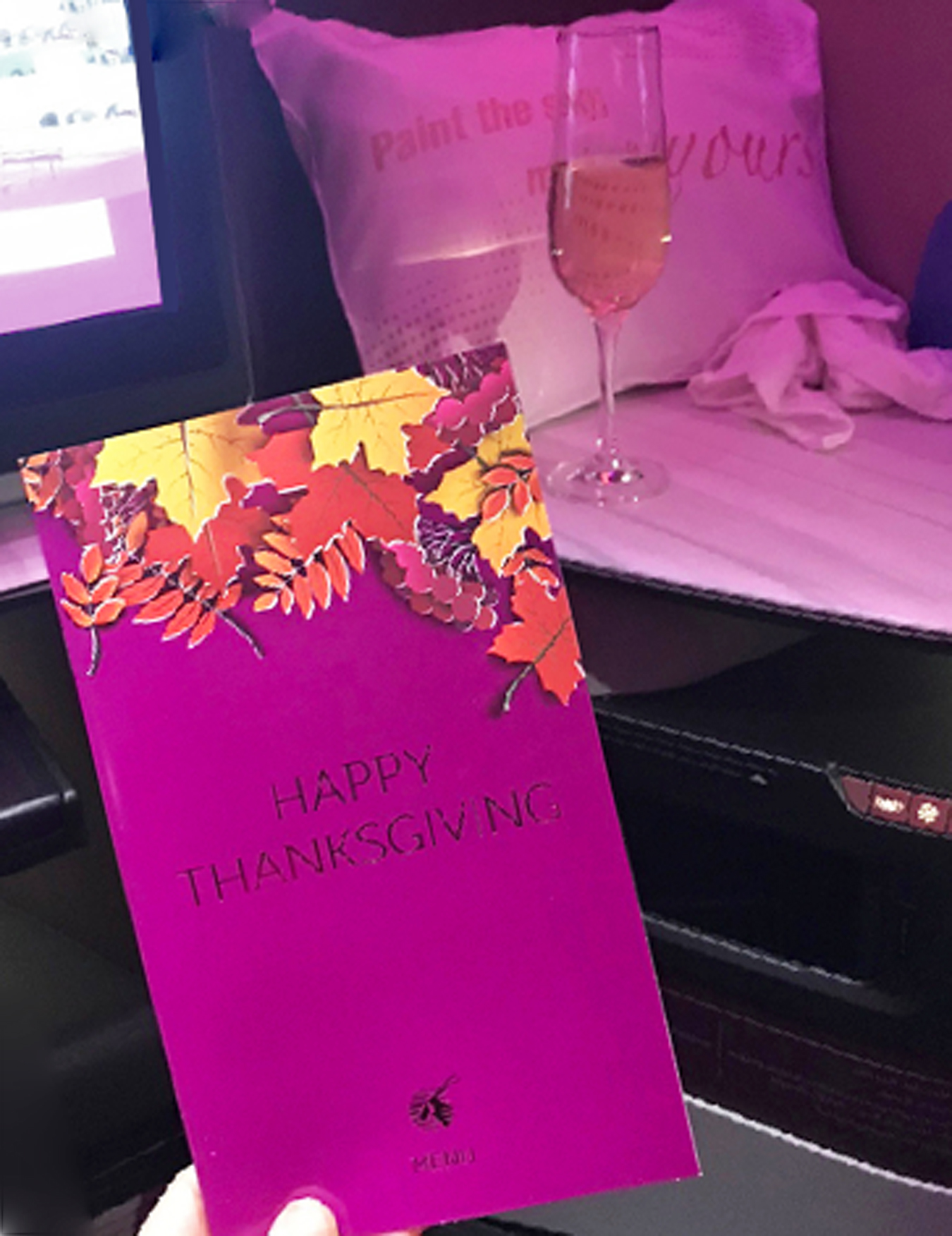

November 21, 2023. Cold Turkey.

Looking back, holiday flying has provided me a few of those sentimental oddities a pilot files away in his mental logbook:

One of my favorite memories dates all the way back to Thanksgiving, 1993. I was captain of a Dash-8 turboprop flying from Boston to New Brunswick, Canada, and my first officer was the always cheerful and gregarious Kathy Martin. (Kathy was one of three pilots I’ve known who’d been flight attendants at an earlier point in their careers.) The Dash-8 had no galley, but Kathy brought a cooler from home packed with food: huge turkey sandwiches, a whole blueberry pie and tubs of mashed potatoes. We assembled the plates and containers across the folded-down jumpseat. The pie we passed to the flight attendant, who handed out slices to passengers.

Quite a contrast to Thanksgiving, 1999, when I was working a cargo flight to Brussels. It was the custom on Thanksgiving to stock the galley with a special holiday meal. The three of us were hungry and looking forward to it. The trouble was, the caterers forgot to bring the food. By the time we noticed, we were minutes from departure and they had already gone home for the day. We always checked the galley prior to leaving, and I thought I might cry when I pulled open the door and saw only a can of Diet Sprite and a matchbook-size packet of Tillamook cheese.

After a desperate radio call to ops, one of the guys upstairs drove out to McDonald’s and came back with three greasy bags of burgers and fries. Who eats fast food on Thanksgiving? Pilots in a pinch.

Just a few years ago I spent most of Thanksgiving day on board a Qatar Airways A350 en route to a vacation in Armenia. Thanksgiving is unknown outside the U.S., but Qatar featured an autumn-themed holiday menu that day in business class. A nice touch, I thought, and something I wish our own airlines did.

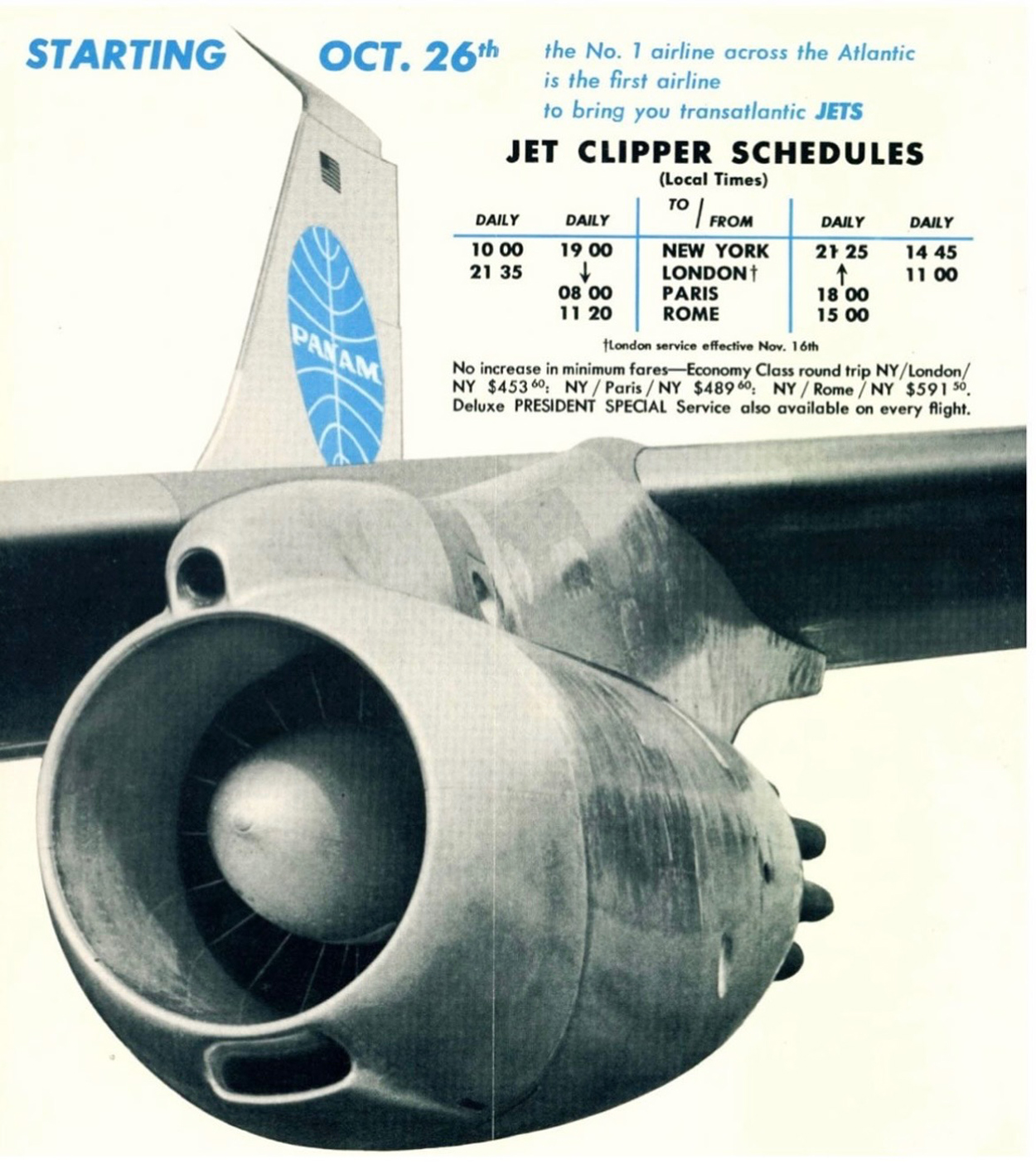

October 26, 2023. 707 Remembered.

Today marks the 65th anniversary of the Boeing 707’s entry into commercial service. The 707 was America’s first jet, launched by Pan Am on October 26th, 1958, between New York’s Idlewild Airport (JFK today) and Le Bourget Airport in Paris.

Debut of the 707 wasn’t as momentous or revolutionary as the 747 would be twelve years later, but it was certainly a milestone. Passengers could now fly at double the speed, and double the comfort, than they could in any propeller-driven plane.

The Brits had been first into the Jet Age with the de Havilland Comet. The Soviets then followed with the Tupolev Tu-104. But the Comet was tragically beset by a series of crashes and withdrawal from service, and the Tupolev was, well, a Tupolev. So while the 707 was actually third in line, it became by far the most successful of the new jets, quickly changing the face of air travel.

As you can see from the graphic, in 1958 an economy round-trip ticket from New York to Paris cost $489. That’s over five-thousand dollars in today’s money. The advent of jets — particularly the 747 later on — would make long-haul flying affordable to millions of people, but cheap mass travel as we know it today was still decades away.

The Boeing 737 still uses the same nose-section architecture of the 707. Those old-fashioned looking cockpit windows you see on a brand-new 737 MAX look that way for a reason: they’re a nearly 70 year-old design.

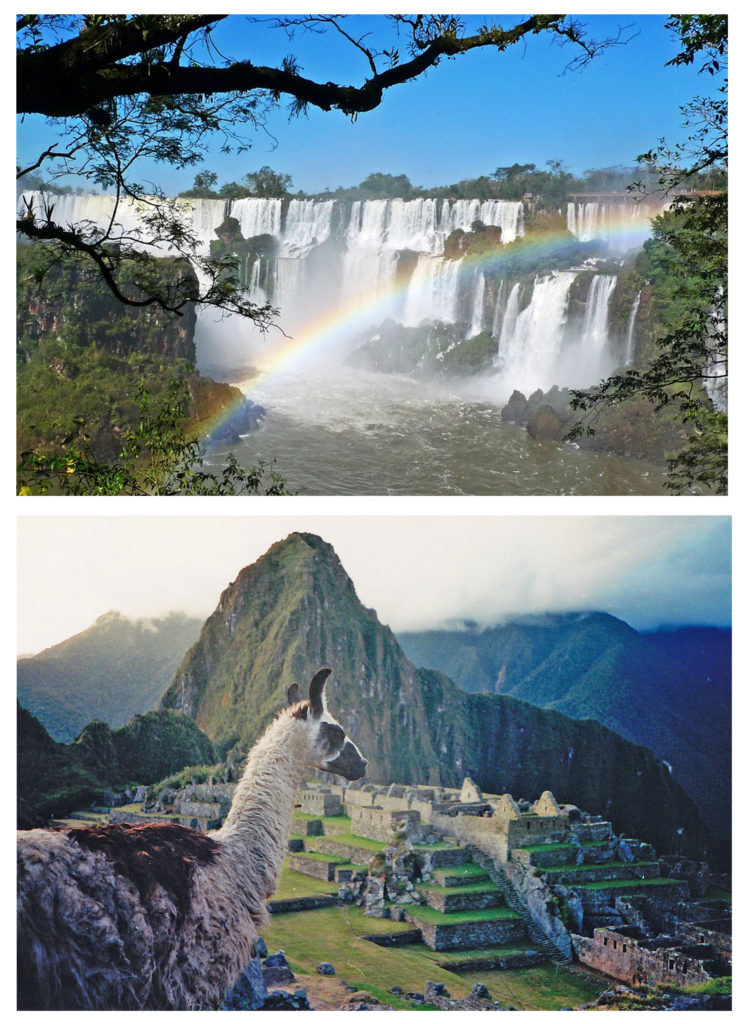

October 14, 2023. Africa Deluxe.

This site has been quiet lately, I know.

The first reason is that I’m lazy. The second reason is that I’ve been on vacation. Below are two photos taken last week in Tanzania. Pardon the diversion, but in lieu of anything aviation-related, readers are invited to check out my Instagram stream view my latest travel photos.

September 19, 2023. Going Around.

Here in Boston the other day, a United Airlines jet performed a go-around just prior to landing due to a non-critical traffic conflict. That’s when a plane, at some point prior to touchdown, breaks off its approach and zooms up again. “Aborted landing” is a sometimes-used term that means the same thing.

The incident made the local news because… well, just because. Passengers “gasped,” according to FOX 25 News, which ran both online and TV segments about the incident.

I say “incident,” but only for lack of a better word. Go-arounds can be unsettling for nervous and even non-nervous flyers, but I can’t overemphasize how routine the maneuver is for pilots. And as I’ve written before, the transition from descent to ascent, however abrupt, is perfectly natural for an airplane. The noises and sensations make a go-around feel a lot scarier than it is.

Neither are most go-arounds performed in response to some imminent danger or catastrophe. I notice the FOX story contains this line: “When a go-around occurs, the air traffic controller and pilot are said to be working together to ‘prevent an unsafe condition from occurring.’”

That’s a direct quote from my book, by the way, and from an earlier post on this site. They obviously saw it, but didn’t attribute it for some reason. They used the “said to be,” to avoid citing me directly. The reporters, to their credit, make a decent effort to point out the harmlessness of go-arounds, but the fact this was a news story at all is, for a pilot, a little annoying.

I’m typically at the controls for a go-around once a year or so, on average. That doesn’t sound like a lot, but the maneuver is straightforward and we practice them all the time in the simulator.

RELATED STORY:

Photo courtesy of Patrick Tomasso/Unsplash.

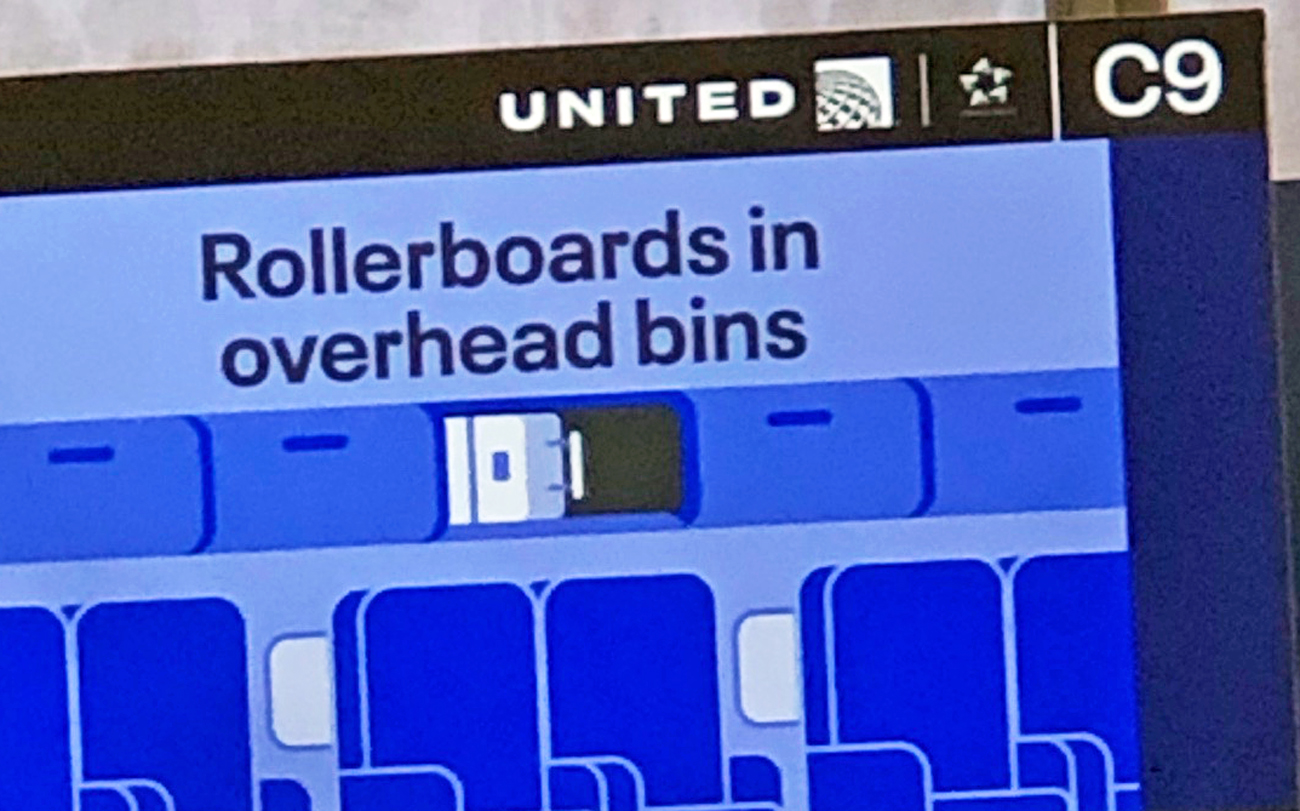

August 30, 2023. Rolling On.

Yeah, this again.

I’ve written before of my disdain for use of the term “roller boards” (or the compound, “rollerboard”) in describing wheeled carry-ons. I’ve been hearing this lazy mispronunciation more and more, usually from flight attendants: “Ladies and gentlemen, please place your roller boards into the bins handle-first.” My what? We picture a wooden plank with wheels on it, or a surfboard strapped with roller skates.

What they’re meaning to say, of course, is roll-aboard. It’s a carry-on with wheels; you roll it aboard. This shouldn’t be difficult.

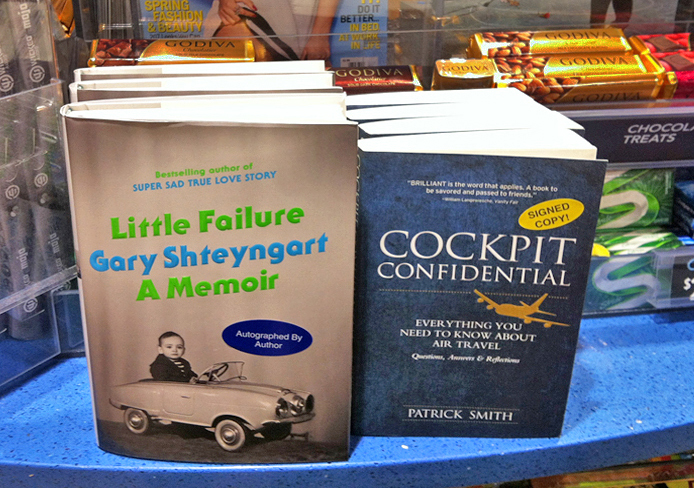

Well even airlines are using the garbled version now, as the photo above shows.

I worry this battle is lost.

Related Stories:

DAMN THE SPINNER BAG.

ET TU, GARY SHTEYNGART?

Photo courtesy of Hesh Lee.

August 28, 2023. Medical Records Controversy.

You may have seen the articles this week about the pilots suspected of concealing medical issues from the FAA. Airlines pilots undergo twice-yearly medical evaluations in order to maintain flight status, and some of the criteria relies on self-reported visits to doctors or other health professionals. As many as 5,000 former military pilots may have neglected to report certain treatments — the same treatments they were simultaneously receiving benefits for through the Veterans Administration. And, apparently, most of the concealed incidents involve mental health issues.

Let’s face it, the flying public doesn’t want to hear the words “pilots” and “mental health” in the same sentence. But a pilot seeking assistance with a stress or anxiety issue — or even for depression — is not by definition an unsafe pilot or one that’s a menace to the traveling public. As I stated in a prior post, the idea that a depressed individual, or one otherwise seeking treatment for any mental health problem, is likely to be a dangerous individual, is an ignorant and unfair presumption about the nature of mental illness. And the fact is that people in any line of work are sometimes in need of help, including those with lives in their hands, be they pilots or neurosurgeons or subway drivers or anyone else. Because this story involves pilots is not a reason to sensationalize it.

Frankly, I’m a little surprised by the news, because the FAA has grown a lot more progressive when it comes to pilots and mental heath. Most conditions and treatments do not mandate automatic grounding; even certain anti-depressants now are permitted, albeit under a supervised regimen. Airlines, too, have worked hard to to de-stigmatize the issue, encouraging employees to seek whatever help they need. Similar to the successful HIMS program dealing with alcoholism, it’s a proactive approach that is safer in the long run than scaring workers into hiding their problems.

There’s always the possibility, it hardly needs saying, that this controversy is less about mental health than about individuals cheating the VA to collect benefits. At which point it becomes a different conversation entirely.

Either way, each case will need to be looked at individually. I suspect — and this is wholly my hunch — things aren’t as scary as the media makes them sound. Worst case, it was likely pilots acting out of embarrassment rather than hiding unsafe conditions. That stigma might be tougher to break than expected.

For more, see my earlier article, below…

Related story:

PILOTS AND MENTAL HEALTH

August 21, 2023 Near-Miss Hysteria?

Just a quick comment on this week’s New York Times article about the uptick in near-collisions between commercial jets, both aloft and on runways.

The story is alarmist in spots, but overall it’s not wrong. The dynamics are pretty simple: we have increasingly crowded skies and a heavily understaffed air traffic control system. In no way is this a healthy combination.

Still it’s not as scary as it seems. The most important thing to remember is that more planes are flying than ever before. Thus it stands to reason that the number of near-misses or runway incursions will be higher than it used to be. The critical stat, which is obscured by other data, some of it anecdotal, is how many incidents, and of what severity, we are seeing per departure. Is this number up or down? I don’t really know. The article itself acknowledges that it’s unclear to what extent a higher number of incidents is due to better data collection, while FAA statistics show no significant change in the frequency of on-the-ground runway incursions over the last several years.

If, worst case, we are less safe, statistically, bear in mind that less safe and unsafe are different things. I fly for a living; I’m in the air all the time. Am I concerned? Absolutely. And the fact that we allowed our ATC system to become so understaffed is a national shame. Yet another case of terrible decision-making induced by COVID. But do I feel the skies are unsafe, or that a catastrophe is imminent? No.

Beware, also, of terms like “near miss.” This is a subjective expression that can mean different things, most of which aren’t as frightening as the words imply.

Lastly, while the threat of ground collisions is a tougher problem to tackle, an airborne collision is an extremely unlikely event. Modern commercial planes are equipped with sophisticated anti-collision technology, which is always there as a safeguard in the event of an air traffic control error.

Contrails photo by the author.

June 16, 2023. Going Paperless.

Emirates has announced they’re eliminating paper boarding passes. Passengers will now rely on a digitized version on their smartphones.

Expect other carriers to follow. You’ll be told this is intended to make the check-in and boarding experience easier. You might hear the word “streamlined.” In reality it makes it more cumbersome and annoying. It’s up there with restaurants using QR codes in place of traditional menus. Instead of relying on the simplicity and and user-friendliness of something tangible, we now have to fumble with our phones.

As most travelers are aware, digital boarding passes already are a thing. But at most airlines the option for a hardcopy pass remains, and in many situations is preferable.

Then there’s the sentimental aspect of it. I’ve always loved the heavier, cardboard boarding passes used on many long-haul flights, and I’ve kept them as souvenirs. Many flyers do the same — the way people save ticket stubs from concerts and other memorable events. They’re keepsakes. Not being able to do this any more is another small way of making the air travel experience less special.

First went the boarding pass wallet. Now goes the pass itself.

Photo by the author.

Related stories:

THE POST-PANDEMIC HOTEL ROOM

HOMAGE TO THE BOARDING PASS WALLET

May 31, 2023. Departure Wing.

Airport art, and there’s a lot of it these days, can be hit or miss. We applaud any attempts to make the passenger’s experience a little less tedious and austere, but most of it, lets be frank, is just filling space.

One soaring exception is “Little Wing,” a piece by California artist Krysten Cunningham. It’s part of the LAX Art Program, and can be seen in Los Angeles in terminal 3, just before the security checkpoint. The feather-pattern wing shapes are formed by a geometric lacing of white rope set against a sky-blue background.

It’s bold and clever and handsome, evocative of flight while avoiding cliche. I’ve seen a lot of airport art in my travels, and this is my favorite piece thus far. It’s scheduled to be in place until 2024. They should leave it up for good.

Photo by the author.

April 1, 2023. Great Moments in TV History.

If you’ve seen the new Netflix documentary about the MH370 mystery, maybe you caught my three-second nonspeaking cameo. It’s in the first episode, maybe about halfway through. It’s momentary footage from an old CNN interview back in 2014. I appear on a split screen with three other talking heads.

No, not the handsome Jeff Wise on the right, or Piers Morgan, on the left, who was asking the questions. I am the one with no hair, two chins, the bile-colored shirt and a look of angry exasperation. More of a scowling head than a talking one. I don’t remember the conversation, but I was obviously annoyed by something. My facial gestures are hilarious. I appear twice, for just a second or two each time.

As to the show itself, I couldn’t get past episode two, with all its conspiracy-theory nonsense. If you wanna know what I think about the missing flight, try the links below…

Related Stories:

March 27, 2023. Senegal Redux.

This past weekend I was back at the Pullman hotel in Dakar, Senegal, for the first time in a decade. (The Pullman — specifically its old room service menu — makes a cameo in chapter four of my book, some of you might recall.) It was mostly the same as I remembered, except for one thing.

As in the old days, we all got rooms on the east side of the building. Riding up the elevator I was excited, remembering those wonderful views of the harbor and Goree Island. But a surprise was waiting.

The top photo shows the view from my room in 2009. The lower photo shows almost the identical view in 2023. Speaks for itself. Progress or something.

The curved building with the triangular top is an old property that I once nicknamed “the Graham Greene Hotel,” because it reminds me of the sort of place where the famous novelist would have stayed, making journal entries in a sitting room with potted palms and a ceiling fan. I was pleased to see it’s still there, and looks like it’s been renovated.

March 27, 2023. Tenerife at 46.

With so many runway incursions in the news, it’d be remiss of me (or else a gesture of the poorest taste) not to mention that today marks the 46th anniversary of the collision at Tenerife — the worst disaster in aviation history.

I was only nine at the time, but I remember my father calling me to the TV as the news showed grainy footage from an island I’d never heard of.

Related story:

March 8, 2023. Pacific Plunge.

In mid-December, a United Airlines 777 descended rapidly towards the Pacific Ocean shortly after takeoff from Maui, Hawaii, coming less than a thousand feet from the water before safety climbing away again. The incident was under investigation by United and the FAA, but otherwise hadn’t garnered much attention. Then the media got wind of it, and now it’s everywhere.

To this point I’ve avoided any commentary or statements. The lack of hard info makes speculation and conjecture risky. Even in pilot circles little is known. But considering the level of hype this story is getting, I should probably say something. So here it is:

The rumor going around — again, it’s a rumor — is that the pilots went directly from flap setting 20 to flap setting zero (up) just after takeoff.

Normally, the flap and slat retraction sequence takes place in increments, as you accelerate during climb. Hitting a certain speed, the flying pilot calls for the next position. The monitoring pilot then verifies the correct speed and acceleration, and brings the flap lever to the proper setting.

The takeoff flap setting in a 777-200 can be 5, 15, or 20, depending on runway length, weight, and other factors. As a ballpark rule, the shorter the runway, the higher the setting. Less runway equals more flaps, in other words, to help the plane generate as much lift as possible in the shortest time.

Flaps 20 would be the expected setting for takeoff from Maui, where the runway is stubby. The plane would lift off at a relatively low speed, then accelerate through a series of “gates” during which the flaps are brought up in steps. Going straight from 20 to zero would suddenly leave the plane in severe danger of stalling. And if that’s what happened, we presume the “dive” toward the ocean was the crew’s attempt to gain speed and protect themselves from a stall. The correct move, in that circumstance. Perhaps the flaps were re-extended as well; we don’t know.

Indeed, we don’t really know anything. Whether things happened as described, I have no idea. This scenario — or some similar version of it — is certainly possible, but it’s hearsay at the moment. If things did occur as described, and the pilots bypassed the normal retraction sequence, the question is why. It surely wasn’t intentional. A misunderstood command, maybe, compounded by the second pilot’s failure to verify? Something like that?

Meanwhile, a different rumor describes a significantly different chain of events, this one involving an incorrectly set altitude window and subsequent VNAV mode activation… It gets technical; I won’t bore you with the details. From what I’ve been hearing, the investigators’ main focus is on a breakdown in crew coordination. What that means, exactly, remains to be seen. We’ll have the whole story eventually.

Photo courtesy of Unsplash

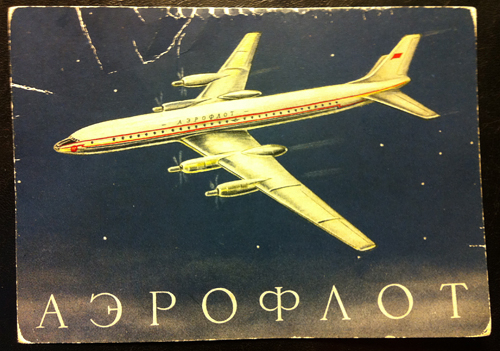

February 10, 2023. Aeroflot Centennial.

We’re not supposed to say nice things about the Russians these days, but congratulations to Aeroflot. The Russian carrier celebrated its 100th birthday last week, and joins the short list of airlines (KLM, Avianca, Qantas) to hit the centennial mark.

Most people don’t remember that in its ’60s and ’70s heydays, Aeroflot was by far the largest airline in the world, carrying roughly as many passengers as all of the U.S. majors combined. With the breakup of the Soviet Union it fragmented into dozens of independent airlines, but a core Aeroflot was kept intact, and it remains today the de-facto national carrier of Russia. It’s not the airline it used to be, but a hundred years is a hundred years. So happy birthday to one of history’s oldest and most storied airlines.

What I love best is that they’ve maintained their beautiful, communist-era hammer and sickle logo. Sure it’s anachronistic, but it’s a classic. “Iconic” is one of the most overused English words these days, but here it’s apropos.

I flew Aeroflot on a couple of short routes — Helsinki to Moscow, and then up to Leningrad — in 1986. These were still Soviet times, and the planes were Tupolevs. I have no photos from those flights because passengers weren’t allowed to use cameras.

Russian fleets are predominantly Boeings and Airbuses these days, but in earlier decades it was all Soviet jets. The design bureaus of Andrei Tupolev, Sergei Ilyushin, and, down in Ukraine, Oleg Antonov, produced a variety of prolific models, a few of which are still flying.

The old Soviet planes are usually described as knockoffs of Western jets, but this is only somewhat fair. The three-engine Tu–154, for example, was a 727 doppelgänger; then again, the 727 was itself styled on the De Havilland Trident. It could be hard to tell who mimicked whom.

Guilty as charged, though, when it comes to Tupolev’s Tu-144, a.k.a. “Concordski.” The mantis-like –144 beat out the Anglo/French Concorde by two months to become the world’s first supersonic commercial aircraft, and its development is a wild tale of Cold War espionage complete with Concorde specs smuggled into Russia by train, concealed in toothpaste tubes. Faster and bigger than Concorde, the –144 began flying cargo missions in 1975, then later carried passengers on the always glamorous Moscow-Alma Ata pairing. Though quickly withdrawn from service, it flew research missions into the 1990s.

Postcard (top) from the author’s collection.

January 31, 2023. Jumbo Finale.

Earlier this week in Everett, Washington, the final Boeing 747 was delivered.

I’d been invited to attend the ceremony, but a prior commitment kept me away. Which is maybe just as well, since I find the whole thing pretty depressing. Seems more like a funeral than anything to celebrate.

The 747 was Boeing’s greatest achievement — indeed it was one of the greatest achievements in the whole history of American industry. Boeing has long since lost its way, and there are those who doubt the planemaker will survive long term. To think, the company that conceived something as legendary as the 747 hasn’t designed a truly new airframe in thirty years, and is apparently content churning out 737 derivatives until the end of time.

The final plane was delivered to Atlas Air, a New York-based cargo carrier that is the world’s largest operator of 747s. The plane, registered N863GT, wears a decal near the nose honoring Joe Sutter, the Boeing engineer who ran the 747 design team.

There isn’t much I can say about the 747 that I didn’t say here, in 2018, when the jet celebrated its 50th birthday. It’s nothing if not the most influential and historically significant airliner of all time. And also one of the prettiest.

The 747 entered service with Pan American on January 21, 1970. The Atlas Air jet delivered on Monday was number 1,574 of a production run that spanned five decades. Of the 27 original customers, Lufthansa is the only one still flying them.

When it debuted, the 747 was more than double the size of any existing plane. Yet it was conceived (literally on the back of a napkin), designed, built, and flown, in a period of only two years. Of all its accomplishments, milestones and accolades, that one might be the most startling.

I flew aboard the 747s of Pan Am, El Al, British Airways, Air France, Northwest, United, Delta, South African, Royal Air Maroc, Singapore Airlines, Qantas, and Thai Airways. I’d like to add a few more to that list while I can.

Related Stories:

THE 747 IN WINTER

A LIFE LIST OF PLANES

Photo credit: Paul Weatherman/Boeing

November 28, 2022. The MAX is Back.

Boeing 737s are everywhere. Notice, though, the ones with the particularly ugly winglets and the scalloped engine cowlings. Those are the 737 MAX variants.

If that name rings a bell, it should. The MAX was the jet involved in two notorious crashes — the Ethiopian and Lion Air disasters — after which it spent two years on FAA-mandated hiatus, during which its twice deadly stall-avoidance system was redesigned, and pilot training protocols modified. The jet re-entered service in November, 2020, and has since settled in without any hiccups. And without much notice, for that matter.

The purpose of this post is to gloat: I told you so. If only I had a dollar for every time someone insisted the jet would never be back. Or, that if it did return, passengers would refuse to step aboard. Which was nonsense from the start — that second part especially. The vexed legacies of the Comet, the DC-10, and even the 787 attest to the flying public’s willingness to forgive, forget, or both. This was no different. As I predicted would happen, that earlier anxiety has evaporated, and nobody, best I can tell, is acting afraid.

Which is fair enough. There’s no need to avoid the MAX.

I’m no fan of 737s, but my reasons aren’t related to safety. I flew a MAX from Miami to Medellin, Colombia, about a year ago. What concerned me wasn’t the possibility of crashing, but discovering that American Airlines has no entertainment screens even in first class!

Related Stories:

BOEING’S BELEAGURED MAX HEADS BACK INTO SERVICE

THE PLANE THAT NEVER WAS

October 13, 2022. Instagripe.

You’ve done a good job staying clear of the whole social media thing. But then your agent says, in that tone of hers, “You really ought to join in.” If only for promotion, she says. It’ll help sell the book. It helps promote the site. Gets your name out there, wherever there might be. And all that.

And so, late to the party as usual, Ask the Pilot now has an Instagram feed. Is that the right word, feed? Channel, account, timeline… whatever you call it, it’s there, and you’re invited to subscribe.

Most of the photographs will be travel-oriented, though plenty too will be of and from airplanes and airports, plus my normal diversions into music, etc. Click the icon or search for ASKTHEPILOT.

We already went through this with Facebook and Twitter, you might recall.

On Facebook you’ll find two pages. The first is the official Ask the Pilot fan page (can it be a fan page if the author himself is creating it?). In addition to the latest posts and stories, it features photos and tidbits that aren’t part of the ATP site itself. The second page is my personal page. This one is for friends, family, and my more devout and obsessive groupies.

Lastly is Twitter, from where I normally tweet links to the newest stories.

April 13, 2022. The Iranian Griffin.

Man, deadheading Iran Air crews really have it tough. It must get claustrophobic in there. (Photo taken at Amsterdam-Schiphzl.)

Very funny. That’s not for the crew, of course. It’s for their luggage. Outside the United States, air crews embarking on multi-day assignments travel with large, hard-side suitcases, which they check in prior to flight. The bags are then loaded into designated containers like this one. Hauling a week’s worth of clothes around in a roll-aboard bag is mostly an American thing.

Iran Air’s peculiar logo is inspired by the character of Homa, a kind of bird-horse-cow griffin, seen carved on the columns at the ancient Persian site of Persepolis. The symbol was designed 1961 by a 22 year-old Iranian art student named Edward Zohrabian, and has been used ever since. It’s an old-fashioned design for sure. It’s also vaguely fetal and creepy-looking. But here’s hoping they keep it, if only for posterity. It’s just a matter of time, I worry, before this enduring mark is dustbinned for some stupid swooshy thing.

Related Story:

February 7, 2022. New Look.

After a long delay, I’ve at last gotten around to introducing a new logo. Refresh your browser, and behold.

Try not to hate on it. If you find it unexceptional, remember that I subscribe to the belief, espoused by more than one famous designer, that a truly effective logo must be unencumbered enough for a child to draw freehand, from memory, with a pencil. It should not rely on colors, textures, or complicated details. Hence the simplicity.

Regular readers know of my disdain for the “swoosh” motifs that have become so commonplace in modern branding. Hopefully that circular arrow isn’t too much of a violation. It’s a swoosh, I guess, but it conforms to the above rules and doesn’t feel gimmicky to me.

I wanted to stay with the basic elements of the original logo: the arrow, the globe, the plane. The arrow and the globe suggest travel. The plane is a plane, though you’ll notice I replaced the generic propeller version with a 747 silhouette — because of course I did. There’s no “official” color for the mark. It looks good in gold, white, black. It’ll often be set against a navy blue field, as that’s the background color of the website, but the pattern itself is the important part, not the colors.

Now I can finally get some hats and t-shirts printed up.

I had nothing to do with the old logo. It was assigned to be by the editors at Salon.com twenty years ago, when I began writing a column for that magazine. I have no idea who created it. Salon also conceived the “Ask the Pilot” name, which I confess I’ve always despised. I might change that too, if the right replacement came along.

February 1, 2022. Winter Skid.

This past weekend’s storm carried me back. Back to 1982, and the Saturday night when a World Airways DC-10 skidded off the end of a runway in Boston.

It was January 23rd. The flight, with 212 people aboard, had originated in Oakland, California, with a stopover in Newark. At 7:36 p.m. the plane landed on Logan International Airport’s runway 15R — the airport’s longest stretch of pavement. The weather was neither stormy nor especially cold. In fact, it was 38 degrees with light rain. The runway, though, was covered in hard-packed snow from an earlier storm, which had turned the accumulating rainwater into a frozen glaze. The plane landed long and fast, missing the intended touchdown point. A braking report, some two hours old, rated the runway braking action as “fair to poor.” In truth it was “poor to nil.”

Unable to stop, the plane rolled past the end of the runway, veered to the right, then lumbered down an embankment into a shallow section of Boston Harbor. The forward-most section of the fuselage, including the cockpit, galley, and the first row of seats, broke off and fell forward, filling with icy water. There was no fire, however, and at first it was assumed that everyone had survived. It wasn’t until three days later that authorities realized two passengers were missing.

The missing people were Walter and Leo Metcalf, a father and son from Dedham, Massachusetts. They’d been sitting in the section that had snapped off and become submerged. The Metcalf’s bodies were never found, and to this day some believe they faked their deaths as part of an insurance scam. More likely, the two men, neither of whom could swim, were swept out to sea by the tide.

Two days after the crash, on Monday, I was at the airport, flying to La Guardia with my mother on the Eastern Shuttle. I was in tenth grade. I had a window seat, as always, and as our A300 taxied along the perimeter, I could see the red, white and gold DC-10, its nose section broken cleanly away, as if cut with a saw, still sitting there in the harbor. They had already covered over the “World Airways” titles with a tarp.

Forty years and millions of landings later, the Metcalfs are still the last airline passengers to die in an accident in Boston.

World Airways, founded in 1948, was predominantly a charter carrier, but had been trying to get a foothold in the scheduled services market. This didn’t last long, and the company went back to its roots, offering passenger, cargo, and military charters that spanned the globe. World went out of business in 2014.

Related story:

December 3, 2021. Odd Angles.

This photo, snapped at LAX, shows a segment of that airport’s Tom Bradley Terminal. Now, I’m all for architectural flourish, but this manic convolution of angles makes my head spin. Have you ever seen such a complicated design?

The interior of the Bradley is equally disorienting. Arriving from overseas the other day, we endured an incomprehensible series of ups, downs, lefts, rights, switchbacks and escalators before finally reaching the immigration hall.

This is not unusual. I had a similar experience at Miami a couple of months ago. The journey — and it was very much a journey — from jetway to the passport kiosk was like finding one’s way through a topiary maze.

Why? Why are so many airport buildings constructed like this? Is it simply to drive the price up?

Strikes me that airport terminals should better resemble railway terminals, with a large central hall and offshoots for boarding and deplaning. Organized and simple, with a minimum of twists and turns. Such a blueprint, as many of the grander railway terminals have proven, still provides ample opportunity for the designers to show off.

Indeed many airports follow this model, to varying degrees. But many do not, and passengers are left to navigate their way through an origami of architectural excess.

October 13, 2021. The Simplest Things.

What most people are curious about right now is the plight of Southwest Airlines, which was forced to cancel hundreds of flights over the past several days. I wish I had some special insights into what’s going. Alas, it’s as confusing to me as it is to you. Staffing issues, pilots upset over vaccines, bad weather, air traffic control snarls… it’s all of the above, maybe. Meanwhile it’s funny how the airlines continue taking their 15-minute turns of infamy. Delta, American, Spirit, Southwest; each has had its well-publicized spell of operational breakdown over the past year. Who’s next?

What I’d really like to talk about, though, is something even more frustrating and confounding: the lack of fold-down cup holders on U.S. carriers.

This photo was taken last week aboard an Avianca flight in Colombia. The plane was an Airbus A320, on a quick internal hop from Santa Marta to Bogota. One sees these nifty devices on foreign airlines all the time, but virtually never on American ones. Why? It’s nice to have your beverage there in front of you without having to deploy the entire tray. There’s more room to move around, and getting in and out of the seat is easier. As a bonus, you can use the thing as a hook for your headset cord or earbuds. The one above even has a little nook behind the ring, to store your milk and sweetener.

Speaking of trays, notice how the one shown is hinged in the middle, allowing you to deploy it only halfway, giving you additional space, if you want it. Another useful idea.

I know, I know, of all the things to complain about. And airlines, rightly, put the bulk of their cabin investments elsewhere. But considering the minimal costs involved, why the hell not? These are not expensive amenities.

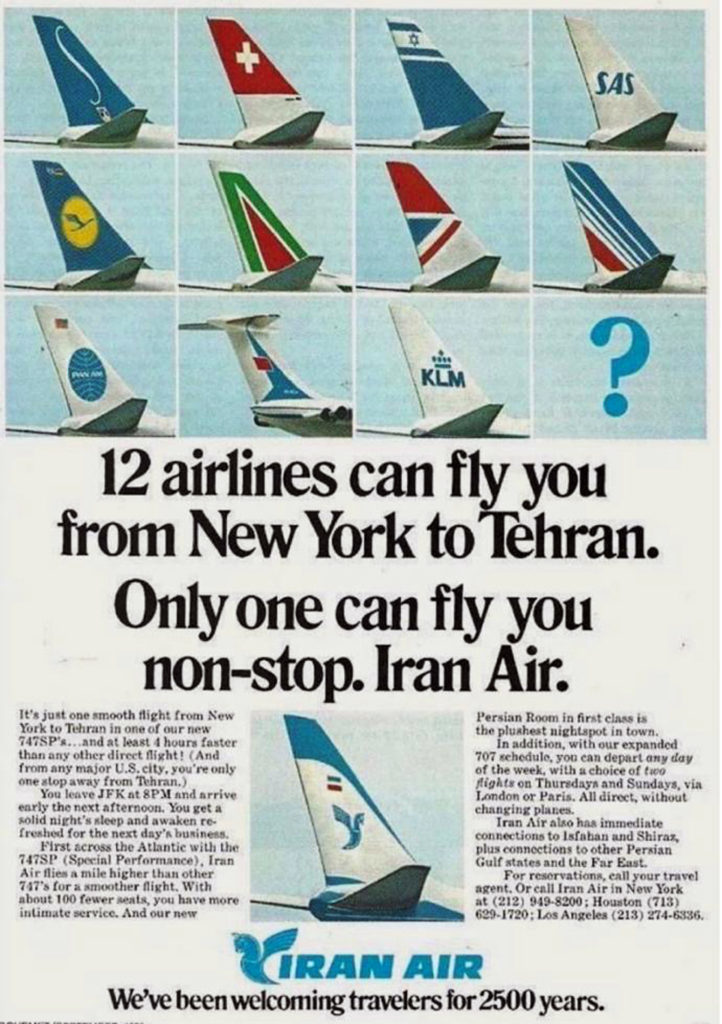

June 22, 2021. Flashback.

For some of us, few things get the nostalgia flowing like vintage airline advertisements. This one is from Gourmet magazine, of all places, in 1976.

There’s a lot to pull from here…

For starters, looking at the collage of tails, we spy three classic carriers that no longer exist: Sabena, Swissair, and of course Pan Am. Of all the many airlines that have gone out of business, few were more historically significant than these three.

The ad also celebrates the advent of the Boeing 747SP — the short-bodied, long-range 747 variant that debuted in the mid-1970s. This focus on aircraft type is a hallmark of older ads and something rarely seen any more. When was the last time an airline spent advertising dollars to boast about a particular plane? It made sense in the 1970s, when models were vastly different from one another and some, like the 747 or Concorde, were media stars. Nowadays, with jets so tediously similar, carriers don’t bother and passengers couldn’t care less.

With that in mind, notice that every tail in that panel except for one features a 747. The single exception is the Aeroflot image, which shows an Ilyushin IL-62. These were the days when you could be at Kennedy Airport and watch ten or more 747s take off in a row.

And, of course, the whole premise of the ad — Iran Air showcasing a new link between Tehran and New York — is itself striking. How things change. Iran in 1976 was still three years away from its revolution, and the country’s national carrier was a regular visitor to New York.

Neither did they shy away from including an El Al tail (top row, third one in) up there with the others. This implies that El Al offered a connecting service to Tehran from New York, presumably via Tel Aviv, which is maybe the most remarkable aspect of the entire page.

I visited JFK in June of 1979, when I was a seventh grader. I remember standing in the rooftop parking lot of the old Pan Am terminal and looking down at an Iran Air 747. (In a box somewhere at my parent’s house, a photo of that plane might still exist, snapped with an old Kodak pocket camera loaded with 110 film.) This was immediately after the revolution began, but about five months prior to the infamous hostage crisis that helped sour US-Iran relations for the next forty years and counting.

Plenty of vintage ads take us back, as the saying goes. The best of them also take in a little history, culture, and geopolitics along the way.

June 3, 2021. Supersonic Hoopla

The future, or just a fantasy?

On Wednesday, United Airlines put out teasers about an important announcement to be made early the next day. Nobody seemed to know, and I went to bed wondering. Are they buying jetBlue? Are they launching another slew of long-haul routes to Africa? Are they reversing course on that abominable new livery?

The answer, which left me more than a little bemused over my coffee on Thursday morning, is a proposal to purchase up to 50 supersonic airplanes from an upstart manufacturer called Boom. The plane, under development, is intended to be a net-zero carbon-emission aircraft, and will run on 100 percent sustainable aviation fuel. It’s slated for test flying by 2025 and entry into commercial service by 2029. United will take 15 of them, with orders for up to 35 more.

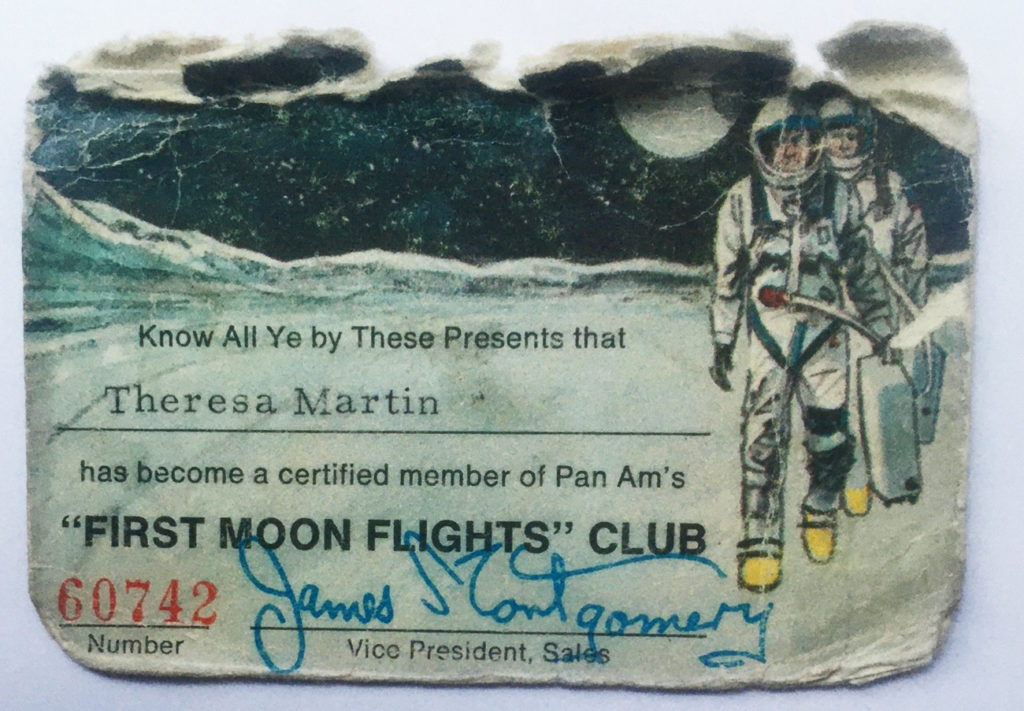

The travel blogs were instantly abuzz with the news, as was the mainstream media. Which is maybe the whole point? Not to spoil the party, but the whole thing reminds me of the time in the late 1960s when Pan Am began selling tickets to the moon.

Okay, it’s not quite as far-fetched, but this is perhaps more of a publicity stunt, or a ham-handed attempt to inflate Boom’s stock price, than a hard and fast plan. Ordering a yet-to-exist supersonic plane is a lot more of a Hail Mary than, say, leasing some additional 787s, and the timeline that United and Boom have put out there is optimistic at best — assuming it happens at all.

Not that there isn’t a market for such a machine, if the costs, and subsequent fares, can be kept within reason. New York-London, Los Angeles-New York, Los Angeles-Tokyo; any number of pairings could support such a service. Potentially. Maybe. Possibly. Define “within reason.” You’re essentially cutting flight times in half. Are enough high-end passengers going to shell out thousands more to fly somewhere in three hours instead of six? Long-haul, premium-class travel is already exceptionally luxurious. How much are those saved hours worth?

And keep in mind, there’s a reason why commercial aircraft today — even the most expensive and most sophisticated ones — travel at more or less the same speeds as they did 50 years ago. Supersonic planes are vastly different than the subsonic kind, and the border between subsonic and supersonic is not an aerodynamic triviality. In a poor man’s version of Einstein’s speed-of-light conundrum, the required energy increases dramatically as you near the threshold. This requires some intensely serious engineering and, one way or the other, lots of fuel. That the Concorde, which took billions to develop, looked nothing like any other plane, was more than a quirk of design, as were its ghastly operating costs. And despite all of its promise, only two carriers ever took delivery of one.

More power to Boom, so to speak. But it won’t be easy.

March 15, 2021. What You Wish For.

From the department of “What Was I Thinking?” I found this in my notes. It’s from August, 2019. I will add no commentary because it speaks for itself. It was something I jotted down with the intent of using later in a posting. That later turns out to be now, albeit in a context I never, ever anticipated…

I’m tired, jaded, frustrated. And if this summer is any indication, I think maybe we’ve stretched this aviation thing as far as it can go. Have you been to an airport lately? The crowds are glacial, the noise levels are insane, the lines and delays are eternal. My flight the other day from Boston to New York — a 35-minute hop — was delayed for four hours because of “flow control” into JFK. And heaven forbid a thunderstorm or two roll in. Our airspace is so super-saturated that the slightest meteorological ripple throws the entire system into anarchy.

As I type this I’m sitting in a terminal at Amsterdam’s Schiphol airport. There are so many people here, surging through the concourses, that you can hardly see the floor — a great, languid river of miserable-looking, stressed-out humanity. Where is everybody going? And why?

“Final boarding for Kigali.” KLM has a nonstop — an Airbus A330 no less — to Kigali, Rwanda, among dozens of other far-flung places. I love traveling, and I wish that I was stepping onto that very flight, right now. Just the same, I have to ask: are there really that many people who need to travel from Europe to Rwanda? Is all of this moving around necessary? All of these people — the innumerable businesspeople; the throngs of college kids with their hoodies and backpacks; the families with infants and the half-dead folks in wheelchairs — constantly on the move, by the tens of millions each week, across entire oceans and continents. In the old days people migrated. Today they simply churn.

For me there’s a troubling paradox: The more I travel, the more I see a system at its breaking point, and the more I’m of the mind that people ought to be staying the hell home.

February 27, 2021. Engine Failure.

Knock on wood, but in all my years of commercial flying, I’ve never experienced an engine failure.* Lord knows I’ve seen enough of them in simulators, but never one for real. I’ve been flying commercially since 1990, so that should give you an idea of how infrequently engines malfunction.

Should it ever happen to you, take comfort in knowing that all commercial planes are certified to fly with a dead engine. This includes the ability to climb away safely should a failure happen even at the moment of liftoff. Any engine failure is considered an emergency, but rarely if ever will it result in a crash.

When an engine does cease running, the process is usually undramatic. Passengers may not even notice. Other times, failures are accompanied by compressor stalls that result in loud bangs and even tongues of flame.

And then you have the kind in which the damn thing flies into pieces. This is the one we call an “uncontained” failure. Here, high-speed shrapnel from the engine’s internal fans, shafts or turbines, exits the cowling (the protective shell that surrounds the engine) and, in some instances, penetrates the wing or fuselage. Uncontained failures are rare, but they can be dangerous.

This was the misfortune that befell United Airlines flight 328 last Saturday. No doubt you’ve seen the cell phone footage, which, as these things go, enjoyed its fifteen (and then some) minutes of fame on YouTube and the major networks. I have to admit, the video is startling.

The engine involved was a derivative of the popular Pratt & Whitney series 4000 turbofan. It is believed that one or more of the engine’s forward fan blades, which in this particular variant are of an unusual, hollow construction, broke apart. The resulting imbalance destroyed the engine and tore the entire cowling off, leaving the powerplant’s innards scarily exposed to the full view of passengers (and, later, the rest of us).

This was at least the third similar incident, and the FAA quickly issued a so-called Airworthiness Directive, mandating inspections on all existing models of this engine. More than 120 Boeing 777s were grounded worldwide.

Although debris did penetrate the lower wing of flight 328, which was headed from Denver to Honolulu with 241 people aboard, there was no cabin breach or serious damage beyond the ripped-up engine itself. Nobody was hurt. The exciting visuals aside, getting the plane safely back to Denver would have been relatively easy for the crew. Planes maneuver quite well on one engine. While this was no ordinary day at the office, it was nothing they wouldn’t be expected to handle.

It could have been worse. In 2018, a passenger was killed after engine shrapnel took out a cabin window on a Southwest Airlines 737. In 1989, the center engine of United Airlines flight 232 disintegrated and knocked out all of the DC-10’s hydraulic systems, resulting in a crash at Sioux City, Iowa, that killed 112 people. The uncontained failure that struck a Qantas flight in 2010 nearly caused a worse disaster.

Such is the inherent danger when dealing with jet engines, which are essentially an interconnected series of fans and turbines rotating at tremendous speeds and tremendous temperatures. Fortunately, these same engines are astonishingly reliable and seldom do things like this happen.

* One day in 1999 I was the second officer on an old DC-8 freighter going from Cincinnati to Brussels. Just as we were “coasting out,” as it’s called — entering the oceanic portion of the flight — a light flickered on indicating a fire in engine number three (the DC-8 had four engines). When I say “flickered” I mean it literally. The light blinked on, blinked off, blinked on, blinked off. Nothing else was abnormal, and none of us believed there was actually a fire. Knowing this antique barge of a plane all too well, we suspected either the sensor was faulty or the bulb itself was on the fritz. We were later proved correct, but we had no choice but to shut down the engine and divert. You can’t simply ignore and engine fire warning and head out over the Atlantic. So we followed the checklist and secured the motor. Then we went to Bangor and had lobster rolls.

PASSENGER KILLED ABOARD SOUTHWEST FLIGHT

January 13, 2021. Airport News.

I knew there was a nugget of goodness buried somewhere in the destruction wrought by COVID-19.

Praise heaven, after thirty long and noisy years, CNN Airport News is going off the air. That’s right, effective March 31st, those infernal gateside monitors are shutting down. In a year with almost no positive news whatsoever, this one gets a gold star.

Few things are more offensive than those yammering hellboxes, hung from the ceiling in every nook and cranny of the concourse, blaring twenty-four hours a day. There is no volume control, no power cord, no escape. Not even employees know how to shut them up (I’ve asked). This isn’t a knock against the content of CNN or any other channel (I’ve been a guest on the network many times). It’s simply a plea to be left alone. Maybe if the damn things weren’t so pervasive I’d feel differently. But they are. You can’t get away from them. They took a somewhat useful idea and vastly overdid it, aggravating untold millions of people in the process.

At one point, some well-intended folks came up with a device called TV-B-Gone, a kind of universal remote that hooked onto your keychain and would silence the “chattering cyclops”* with the push of a button. They mailed me one, and lo and behold it worked… until CNN caught on and installed a blocking device. All hope seemed lost.

And the intent was what? Three decades of noise pollution masquerading as “news” has not kept passengers entertained or better informed. What it’s done is make an already stressful and nerve-wracking experience that much worse. So, good riddance. If it were up to me, the day those TVs fall silent would be declared a national travel holiday. Let us gather ’round the podium and savor the quiet.

Maybe. I hate saying it, but this feels a touch too good to be true. Those monitors and their wiring comprise an awful lot hardware, and, much as I’d love to watch it happen, I just can’t envision it all being torn out and thrown away. Will another network swoop in and take over? Fox? MSNBC? The Trump Travel Channel? I sincerely hope not. I know these things help pay the bills, but there has to be a better, more civilized way. Fingers crossed.

Related Story:

TERMINAL RACKET

November 16, 2020. Around and Around.

Go-arounds, missed approaches, aborted landings. Call them what you will; on Sunday, for the third time in my life, I was on board a plane that made two of them consecutively.

The first two times I was at the controls. In 1991 I was flying a 15-seater into Hyannis, Massachusetts, when twice the plane in front of us failed to clear the runway in time. Then, in 2008, I was flying a 757 landing into La Guardia when ATC twice misjudged our spacing on approaches to runway 22.

This time I was a passenger. I was in row 12, on a regional jet landing in Detroit. The winds were gusting to fifty knots, and the approach had been unusually turbulent the whole way down. I could see the treetops doing pirouettes. At about 500 feet the engines revved, the gear came clunking into the wells, and up, up, up we went. Whether it was crosswind issues or shears from the gusts — or both — I never found out, but something made the approach unstable enough to discontinue. The pilots did what they were supposed to do: break it off and go-around.

The second try was a carbon copy of the first one, and I was a little surprised when the captain let us know we’d be circling around for attempt number three. I assumed, after two good efforts, we were headed for Chicago or Cleveland. This time, he explained, we’d be switching to a different runway where the crosswind component wasn’t as strong. Still, I wasn’t optimist. From the window I watched the branches bending and the water rippling madly across the lakes and ponds, waiting for that tell-tale upward pitch and surge from the engines. Except this time it didn’t happen. We settled gently over the threshold and, plunk, we had arrived. The passengers broke out in applause.

Go-arounds can be abrupt and noisy, scaring the daylights out of customers. For airplanes, however, the transition from descent to ascent is perfectly natural, and a maneuver that pilots practice all the time. For more, see here.

November 11, 2020. With Sam in Dubai

Three friends and I were vacationing in Dubai last week. In the lounge of the J.W. Marriott we ran into Sam Chui, aviation gadabout and airplane photographer extraordinaire. Sam was kind enough to join us for drinks and hors d’oeuvres.

If you’re an air travel nerd, chances are you know exactly who Sam Chui is. The rest of you can familiarize yourselves with his work here. I’ve been an admirer of his photography — and sorely jealous of his luxury travel experiences — for the past twenty years.

The crazy thing is, we’d been talking about Sam Chui earlier that day, with Itamar and Karim both doing hilarious impersonations. Suddenly, that evening, he’s sitting there in the lounge.

June 3, 2020. Back At You.

Air China 747 at Kennedy Airport. Author’s photo.