The Media’s Airplane Problem

January 5, 2014

FEW THINGS mix more poorly than commercial flying and the mainstream media. Seldom is an aviation article free from some measure of distortion, exaggeration, or at times outright nonsense. If you caught my post on the AirAsia crash, you’re already aware of the pair of recent New York Times op-eds that couldn’t get it right. But that’s just for starters.

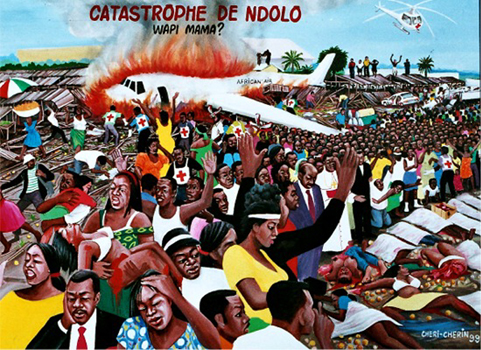

There are hardworking reporters out there who take the extra step to ensure their work is accurate, but they’re the exception. I’m not saying it’s an easy beat — aviation is a field brimming with jargon, stubborn mythology and recalcitrant sources (i.e. airline spokespeople), but sometimes it’s as if they’re not even trying. Especially when it comes to pictures. If only I had a dollar for every time an article or news segment was accompanied by incorrect or inappropriate photography. For instance a TV spot about a particular airplane type, or a particular airline, is accompanied by footage showing a totally different plane or a totally different carrier. Or newspaper article about Airbus shows a picture of a Boeing; an article about Boeing shows an Airbus. And so on.

Here’s one blooper that gets both the aircraft and the airline wrong. The story, carried last month by the Agence France-Presse (AFP), was about a US Airways Airbus A330 that diverted into Rome after several passengers became ill. Notice the caption. The problem is, that’s not an Airbus A330 and it’s not US Airways. It’s a much larger A380 in the colors of Qatar Airways. Not even close on either count.

Have you ever noticed, too, how any and every time a flight diverts somewhere or returns to its airport of origin, be it for a mechanical problem, medical issue, or anything else, the event is described as “an emergency landing”?

In fact the vast majority of what are described as emergency landings are precautionary diversions or returns. Actual emergency landings are rare, and pilots do not employ the term nearly as loosely. The captain must specifically declare an emergency to air traffic control. Situations vary, but generally it pertains to a situation in which expedited air traffic control handling is requested, and/or aircraft status is uncertain. Even then, most emergencies aren’t anything close to the life-or-death scenarios many passengers (or reporters) are prone to imagining.

Another bad habit of reporters is describing virtually any portion of airport tarmac as a “runway.” Taxiways, terminal ramps, etc., are commonly called “runways,” when in fact they are not. I should hardly have to point this out, but a runway is a very specific thing with a very specific purpose: it’s that long and clearly defined strip of pavement that a plane takes off from and lands on.

And while I hate to pile on, allow me to pile on…

I also have a problem with the media’s reliance on aviation academics. It’s customary for reporters to cite aviation professors, aerospace researchers, etc., in their stories. I understand the temptation here, and with certain topics these individuals offer valuable insights. But what reporters don’t realize is that professors and researchers can be highly unfamiliar with the day-to-day operational aspects of commercial flying. This is not their expertise. If the topic is aerodynamics, meteorology, or something statistical, that’s one thing. But for anything that touches the nitty-gritty of airline operations and the SOPs of flying jetliners, academics are often terrible sources.

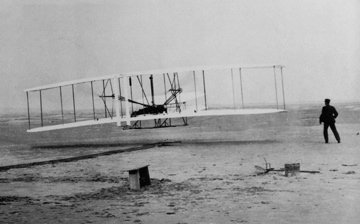

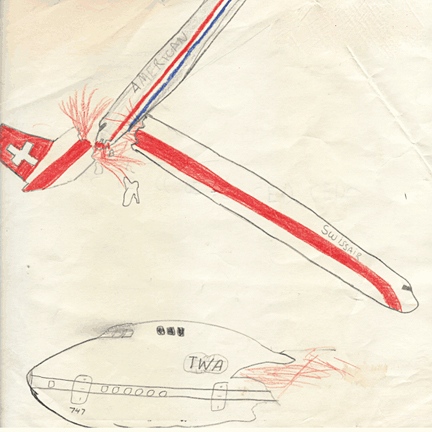

And we haven’t even gotten to Hollywood yet. Movies are the worst. Never mind the more complicated plots involving pilots; half the time filmmakers can’t even get the basics right. I love it when they show a regional jet when they mean to show a long-haul widebody plane. Or when two different models are pictured at different times, intended to be the same plane. For example a 737 is shown taking off. Minutes later we see footage of the same flight landing… except now it’s a 747. It’s just airplanes, nobody will notice, right? Except many of us do. It’s baffling the way Hollywood will go to such extreme efforts and cost to get certain period details correct — automobiles, consumer products, clothing and haircuts — but it all goes out the window as soon as they get to the airport.

Movies we can forgive. The press, though, we hold to a higher standard.

Strange as it might sound, one of the better Hollywood takes was the old film “Airport ’75.” A 747 is struck near the flight deck in midair by a small propeller plane, and all three pilots are taken out (older 747s carried a third hand, the flight engineer). I almost hate to say it, but dangling Charlton Heston from a helicopter and dropping him through the hole in the fuselage wasn’t as far-fetched a solution as it might sound. It was about the only way that jumbo jet was getting onto the ground in fewer than a billion pieces. The scene where Karen Black, playing a flight attendant, coaxes the crippled jumbo over a mountain range was, if not entirely accurate from a technical standpoint, very realistic in demonstrating the difficulty any civilian would have pulling off even a simple maneuver.

I’ve always thought the best and most evocative Hollywood moments are those in which airplanes appear incidentally — as background characters, so to speak, rather than central to the story. In my book I cite the example of the Polish Tupolevs idling on the apron in Krzysztof Kieślowski’s “Dekalog IV.” Best, though, is the old Convair jet that appears with Al Pacino in 1975’s “Dog Day Afternoon.” One of my all-time favorite movies, its final scene unfolds at Kennedy Airport, where bankrobber Pacino is captured and handcuffed against a cop car, his accomplice shot through the head. In the background is a noisily idling jetliner, which Pacino thought would be his getaway plane. The plane is a Convair CV-990, a now-extinct, four-engine jet that was an uncommon sight even in the mid-70s. This peculiar rara avis is shown in the colors of Modern Air, a real life charter carrier at the time. (What a great name that was: Modern Air.)

Dog Day Afternoon was one of few major motion pictures to feature no music whatsoever. There’s no soundtrack, no backing score. Yet that closing scene is all about sound. Airplane sound. The earsplitting whine of the Convair’s early-generation engines, and the roar of unseen planes taking off.

RELATED STORIES:

NOAH GALLAGHER SHANNON’S FLIGHT OF FANCY

“ARGO” GETS IT WRONG