Checked, Set, Roger

September 29, 2015

EVERYBODY has heard the word “checklist.” Most folks know that checklists are a staple in airline cockpits, and they get the gist of it. The term is self-descriptive; you can think of it as a grocery list of sorts — a line-by-line register of specific items, used to make sure that important tasks have been completed, and none skipped. Still, a lot of people don’t understand exactly what a cockpit checklist looks like and how the reading of one is carried out. Pardon the geekiness of what follows, but here’s how it works:

Pilots use checklists for both normal and non-normal operations: for routine situations, for malfunctions, and for emergencies. (You’ll notice I said “non-normal.” That’s a classic aviation-ism, devised in place of “abnormal” for reasons I can’t possibly fathom or explain. It’s a goofy word, but for the sake of realism we’ll stick with it.)

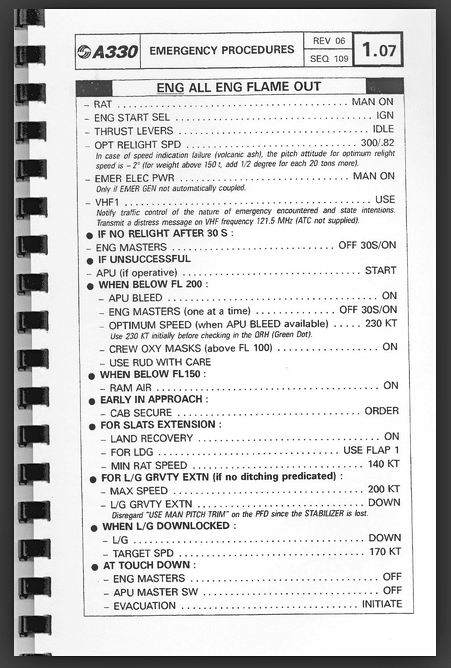

The non-normal checklists are bound together in an overstuffed book called the QRH, or Quick Reference Handbook. This volume contains step-by-step procedures for hundreds of potential situations or malfunctions, from minor component failures to how to prepare for an ocean ditching. The QRH is divided into chapters: electrical, hydraulic, pneumatic, etc. There are at least two in the cockpit: identical copies for the captain and first officer, always within easy reach.

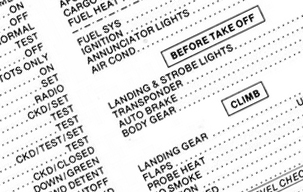

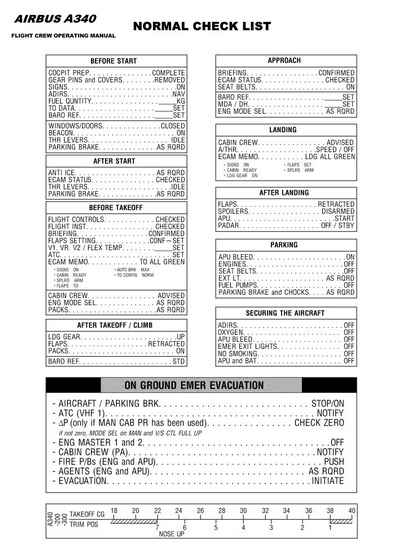

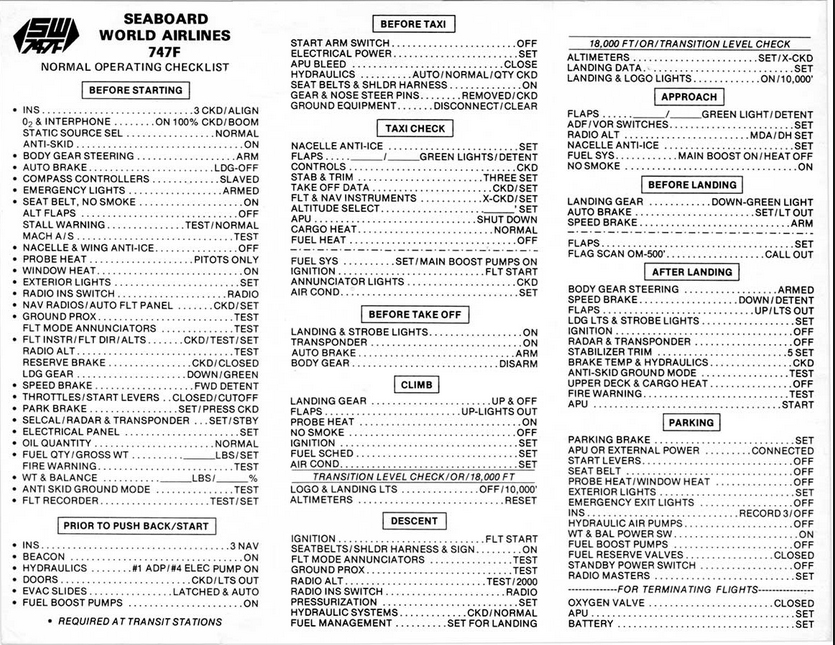

The normal checklists are usually printed on an a card — paper or cardboard — sometimes laminated and often folded vertically and/or lengthwise. A single card will be divided into as many as a dozen separate checklists, each of which will be read aloud depending on the phase of flight. Wording varies airline to airline, but the individual lists will be titled something like this:

PREFLIGHT

PUSHBACK and ENGINE START

AFTER ENGINE START

TAXI

BEFORE TAKEOFF

AFTER TAKEOFF

CLIMB

DESCENT

APPROACH

BEFORE LANDING

AFTER LANDING

SHUTDOWN

Most of these are only five or ten items long and take only a few seconds to perform. The PREFLIGHT checklist is normally the longest, and can have thirty or more steps, depending on the airline and aircraft type. On the newest jets, checklists are presented electronically on a screen — though there’s always a hard copy as well.

Boeing, Airbus, and the other manufacturers devise an initial, standard checklists for every airplane type, and carriers then tweak them. As a result, a 737 checklist at American Airlines will read differently than a 737 checklist at Delta. The basics are always the same, but airlines tailor them in accordance with their training and SOP.

Most of the normal checklists are read aloud in a challenge/response format. One pilot reads the item, and the other pilot calls out the verification. On the ground it’s usually the first officer who reads. In the air, it’s whichever pilot is not physically flying. For instance, using C and R for challenge and response, a LANDING checklist would go roughly as follows (this is a generic example):

C: “Landing gear?”

R: “Down, three green lights”

C: “Flaps and slats?”

R: “Thirty-Five, Thirty-five, Set”

C: “Spoilers?”

R: “Armed”

C: “Autobrakes?”

R: “Three”

The pilot who is reading then says, “Landing checklist is complete.”

Sometimes both pilots are required to call out verification of an especially important item. Challenge/Response becomes Challenge/Response/Response. Trying it again:

C: “Landing gear?”

R: “Down, three green”

R: “Down, three green”

C: “Flaps and slats?”

R: “Thirty-Five, Thirty-five, Set”

R: “Thirty-Five, Thirty-five, Set”

C: “Spoilers?”

R: “Armed”

C: “Autobrakes?”

R: “Three”

At other times, the pilot reading the checklist calls out both the item and the verification. It depends.

The verbal reply to a challenge/response might be a numerical value, an “on” or “off,” or a simple “checked” or “set.” Or, it might be something specific like “down, three green,” like you see above. In that case, the pilots are verifying that the landing gear lever has been selected down, and that the warning lights agree that the gear is down and locked for touchdown. When they say “thirty-five, thirty-five,” that’s a verification that the wing flap handle is set to 35 degrees, and that the associated gauge shows the flaps having in fact reached that position.

When one pilot verifies the task of the other pilot, that’s “crosschecked.”

We also say “roger” a lot. (Or “Rogah.” For fun, I am prone to reading the PREFLIGHT checklist in an exaggerated Boston accent: rogah, radah, transpondah, etc.)

To the outside listener, the smooth, uninterrupted reading of a checklist can be an interesting and curious ballet.

Occasionally, though, a checklist is performed silently, by one pilot. The AFTER LANDING checklist, for instance, is ordinarily silent, the only call being when the first officer says “After landing checklist is complete.” He’s meanwhile made sure the flaps, slats, and speedbrakes are retracted, the trim is reset, the radar is off, and so on.

There also are supplementary checklists, such as those used during oceanic crossings and other not-always-routine operations.

Checklist discipline is important. You always reach for the card, even if you’re 99.99 percent certain that everything is safe and complete. In the airline environment this discipline is taken for granted. In my entire major airline career, I have never once seen a checklist intentionally skipped.

Normal checklists are just that: check lists. You are verifying that tasks have already been accomplished. All the switches, buttons and levers should be in the correct position prior to reading. The pilots will already have run through their so-called “flow patterns,” a choreographed set of steps during which the physical button and switch-pushing is actually accomplished. For example, on the plane I fly, immediately after the engines are started, the first officer’s flow pattern includes, in a right-to-left sweep beginning at the overhead instrument panel, reconfiguring the plane’s pneumatics, turning on the engine anti-ice (if needed), turning on the center tank fuel pumps, shutting off the APU, checking the “recall” function of the main annunciator panel, and one or two other things. The AFTER START checklist then verifies that everything was done.

The non-normal QRH procedures, on the other hand, can more accurately be described as “do lists.” You don’t do anything until you’re instructed to.

That is, except for those times when so-called “memory items” come into play. These are a brief series of steps performed from memory in urgent circumstances, when time doesn’t permit the luxury of breaking out the QRH. Once the situation is stabilized, you refer to the book to make sure you did everything correctly. It will then guide you through whatever else needs to be done.

The QRH checklists can be complicated and go on for several pages. One or both pilots might be involved in the reading and verification, depending on circumstances. Regardless of which pilot’s turn it is to fly, it’s not unusual for the captain to delegate flying duties to the first officer while he or she breaks out the QRH and troubleshoots. During this process, the most crucial tasks — for instance, shutting down an engine — will require dual verification, and both pilots must become part of the conversation. Newer planes sometimes have electronic, on-screen checklists that pop into view when needed, used in lieu or in addition to those in the QRH.

All of this, meanwhile, is separate from the execution of what we call “profiles.” All normal or non-normal flight maneuvers are flown according to a profile: what speeds to fly, what angles of pitch to aim for, when to extend and retract the flaps or landing gear — each of these things, and more, happen at a prescribed place and time. It isn’t about switches, levers or dials. Rather, it’s how you fly the plane. Takeoffs, instrument approaches, go-arounds, and all of the maneuvers in between, follow a specific profile. Thus, at any given airline, all crews are trained to perform the same maneuvers the same way. This ensures commonality and, in turn, safety.

Pilots have been using checklists for decades, and it’s a little surprising that other industries haven’t adopted the concept more widely. Finally their use is beginning to spread into other realms, most notably medicine and nuclear power.

If you enjoyed this discussion, check out the author’s book.