The Airport Lounge Crisis

UPDATE: February 12, 2023

MAYBE MY EXPECTATIONS are out of whack, but I’ve always thought the airport lounge was supposed to be an exclusive sort of place. A place of luxury and comfort, where premium class passengers could escape the noise and bustle of the terminal. In my younger days, before I could afford to travel in the forward cabins, I’d walk past those smoked-glass doorways and think, wow, it must be pretty luxe in there. I mean, isn’t that the point?

Well, as anyone who travels regularly and visits these lounges will attest, this is increasingly not the case.

The main issue is overcrowding. Lounges are often so jam-packed that customers are turned away or asked come back later on. I’ve seen lines going halfway down the concourse. If you do get in, there’s nowhere to sit and noise levels are off the charts.

One night I’m at the airport in Bangkok, at the Thai Airways’ Royal Orchid Lounge, which is shared by the various Star Alliance members. For me access to the lounge is part of the whole premium class experience, and so I left the hotel early to enjoy it. In the entryway vestibule, everything is peaceful, elegant and quiet. The hostess scans my boarding card and welcomes me. But when I turn the corner into the main hallway, everything changes. There must be five-hundred people inside. Literally every seat is taken. There’s trash all over the floor and it’s louder than a football stadium.

After standing around for ten minutes I finally score a seat. I’m wedged between four other visitors. My table is cluttered with the last person’s cups and plates, but if I wait for it to be cleaned, someone else will grab it. There are kids everywhere, and they will not shut up: yelling and crying and running around like it’s recess on the school playground.

The centerpiece of this chaos is an obnoxious guy in a Russian soccer shirt and his belligerent offspring. He’s something of a Vladimir Putin lookalike, sprawled sockless on a sofa with his naked feet hanging over the rail, playing a game on his phone. Around him is a spray of plastic toys deposited by his five — count ’em, five — preschool-age children, shrieking and throwing chips at each other. Every so often Vlad claps his hands and scolds them in lazily indignant Russian. They ignore him and carry on.

And here come the waitstaff with their carts. They’re flinging dishes into the bin, rapid-fire, and it’s BANG, CLANG, SMASH, BANG, SMASH, CLANG.

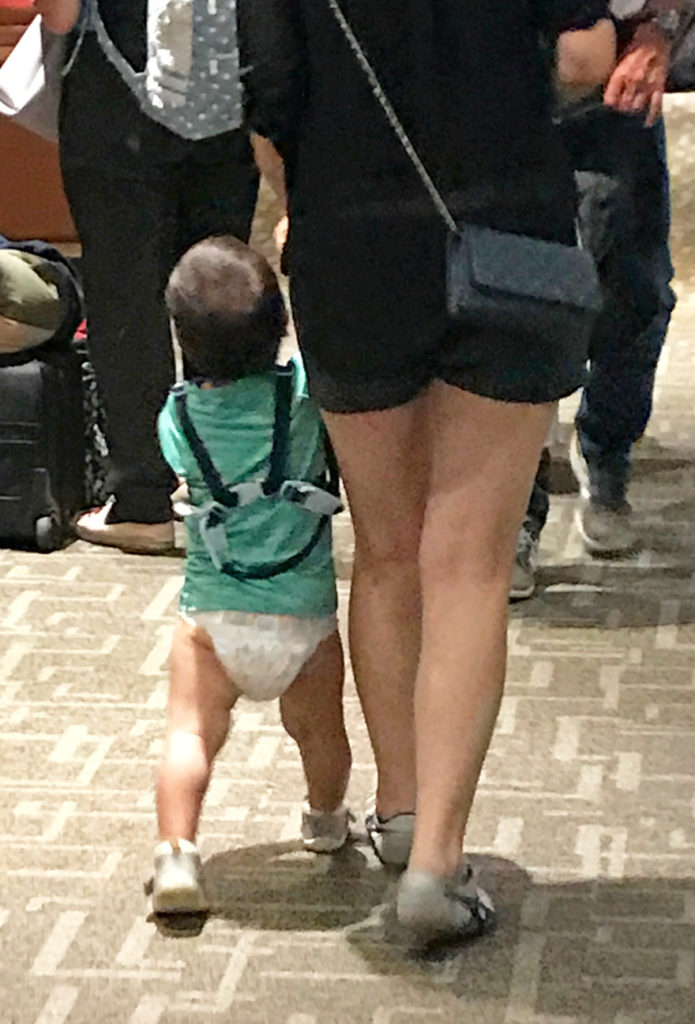

I try not to let it get to me. I distract myself with the buffet, helping myself to a gin and tonic, a miniature pastry-pillow labeled “chicken roll,” and some finger sandwiches made with institutional-looking white bread. But it’s so noisy and crowded that it’s impossible to relax. At one point I look up and can hardly believe my eyes. Walking past me is a mom and her two year-old toddler… in a diaper.

The photo at the top of this post was taken at the Aspire lounge (shared by multiple carriers) at Amsterdam-Schiphol. Every seat was occupied and the morning sun was blasting through the unshaded windows, heating the room like a sauna. At least a dozen babies could be counted, half of whom were shrieking at any given time, while a group of rambunctious, slightly older kids ran amok, throwing themselves over the furniture. Aside from the free food — which kept running out — what exactly was the advantage of being here versus any random spot in the terminal?

Silly me. I remember the first time I stepped into the Cathay Pacific business lounge in Hong Kong, and how, not knowing better, I was literally nervous. I had this idea that I was stepping into some rarefied chamber of privilege where everyone inside would look like like James Bond. I’d be seen as an interloper and asked to leave. Instead, here was a room overflowing with the same people you’d see in any shopping mall, most of them younger than me, in cargo shorts and ballcaps, jostling with baby strollers and wolfing down beer and noodles.

I was in the Avianca lounge at Miami International not long ago. There was a guy, early thirties, sitting across from me, with his headphones cranked so high that everybody within fifty feat could sing along. The music was obnoxious enough, but then I noticed his t-shirt. It was black and emblazoned with two simple words in large block letters. It said… well, here’s a picture of it:

If that’s not an indicator of just how far air travel — even premium class air travel — has fallen, I don’t know what is.

This is by no means across the board, of course. It’s hit or miss, depending on the airport, the airline, and the time of day. The trend, though, isn’t a good one. There are a lot more loud, dirty, and overcrowded ones these days than pleasant or luxurious ones. What was intended to be a place of comfort and relaxation has become a cross between a day-care center and a cafeteria.

The cause is twofold. For one, more people are flying than ever before, in all classes, and/or with whatever mileage or frequent flyer status gets you in. The bigger factor, though, is the rapidly growing number of folks using third-party perks to gain entry. Credit cards, mainly. There’s American Express platinum, for example, and a host of others granting entry through the Priority Pass program.

I don’t know how it happened, exactly, but the number of people accessing lounges via credit card has exploded since the end of COVID. Four years ago the crowds and noise were bad enough. Now the problem is significantly worse. Somehow, in the middle of a pandemic, millions of people went out and acquired high-end cards with huge annual fees.

(In the interest of full disclosure, I’m as guilty of this as anybody, my Priority Pass benefits getting me into the same lounges I’m apt to then complain about.)

I should point out, too, that the same thing is happening in hotels. Have you been to the executive lounge in a Marriott or a Hilton or a Hyatt lately? A topic for another time, maybe, but the mechanics of the issue are no different.

This won’t be an easy one to fix. There aren’t many options aside from tightening up entry qualifications or building bigger lounges. The latter is difficult, if often impossible. The former risks alienating a large number of customers who’ve gotten used to easy entry.

Airline lounges restricted only to premium class passengers do exist, but carriers make a lot of money from those credit card deals, so I don’t see the Priority Pass situation getting better. One idea would be for the card-issuers to increase their yearly fees, seeking out that sweet spot where the number of customers who drop out would be offset by the higher premiums.

I’m not optimistic. Look at airport security as an example, whereby a tediously inconvenient, jury-rigged system became the new normal. Sure there’s PreCheck, but the basic structure of the system is irrational and frankly chaotic. If you could time-travel back twenty years and describe our security protocols to a passenger, he or she wouldn’t believe you. The whole thing would be seen as ridiculous and unacceptable. Yet here we are.

It’s amazing what we grow accustomed to and eventually accept with a shrug. The lounge, as a place of luxury and quiet, may be yet another relic of the past.

Ask the Pilot lounge awards…

BEST: The Emirates first class lounge in Dubai, concourse A. The private boarding bridges, the gourmet food, sumptuous surroundings and complimentary massage. Where to start? And no, your AmEx ain’t getting you in here.

Dubai Decadence.

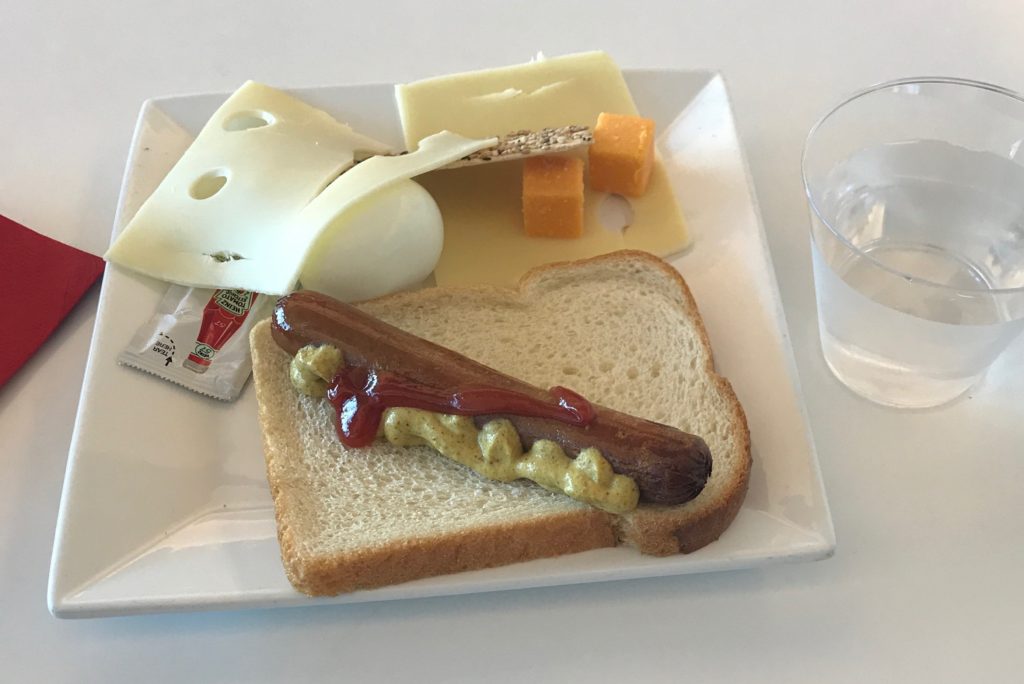

MOST DISAPPOINTING: The Wingtips lounge at JFK’s terminal 4. Another of those shared lounges, which tend to be worse than the airline-specific ones, this is a singularly awful space. Cramped seating, noisy kids, rickety unwashed tables, and it’s always a hundred degrees inside. As for the food…

Bon appétit !

All photos by the author.

Related Stories:

FIRST CLASS, LOW CLASS, NO CLASS. THE PASSENGER HALL OF SHAME

THE SCOURGE OF INFLIGHT GARBAGE

WHAT’S THE MATTER WITH AIRPORTS?