HüSKER Dü WERE A TRIO from Minneapolis. Guitarist Bob Mould and drummer Grant Hart sang and wrote the songs. Greg Norton played bass guitar and chipped in on vocals.

A punk band, you would have to call them, as throughout the early and mid-1980s they toured and recorded primarily within that realm. At heart, though, they were always something else. “Hüsker Dü seemingly defined the punk ethos,” wrote Terry Katzmann, one of the band’s longtime friends once put it, “without necessarily embracing or endorsing it.” Perfectly put.

The band could play louder and faster than anyone alive. When this got constraining, they’d bring in 60s-style pop hooks, psychedelia, heavy metal. Often at once, which to me is the kernel of what made them great. They were never powerful or something else. They were both, everything, all at the same time.

This blending of styles alienated many of the more orthodox fans within the punk scene. It also won the acclaim of many more, and it’s by no means a stretch to consider Hüsker Dü one of the most influential acts ever to emerge from the American underground.

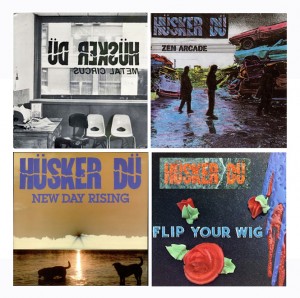

Before its stormy demise in late 1987, the band would release six full-length albums, two EPs, and a catalog of singles and extras. But the pinnacle of all that output was Zen Arcade, first delivered to stores in July, 1984, by California-based SST records.

I remember the day I bought it. Newbury Comics — the one on Newbury Street — on a midweek afternoon, sunny and hot. I was eighteen years-old.

We knew there was an album coming coming out, but weren’t sure when, exactly, it would hit the racks. In these pre-Internet times, news of such things was always unclear and came sporadically, delivered by college radio or gleaned through your network of friends. Sometimes it was a paper flyer glued to a mailbox or tacked to a record shop bulletin board. Nobody was a bigger Hüsker Dü fan than I was, but this latest album, due in the stores at any moment — I didn’t even know the title.

Suddenly there it was, on a rack up front. It was called Zen Arcade, whatever the heck that meant. I picked it up and, hey, what’s this, it’s a double album! As a teenage punk rocker weaned on Black Flag and Minor Threat, with a rather one-dimensional appreciation for music, the very weight of the thing, together with the heady title and the washed-over, almost Impressionist cover art was intimidating. It seemed so arty and grown-up. It also made me curious. What was this strange record?

What it was, and what it remains almost forty years later, is the greatest indie-rock album of all time — if not, in my extraordinarily biased opinion, the greatest rock album, period.

“The most important and relevant double album to be released since the Beatles’ White Album,” bragged SST’s own press release. There was some confidence for you, to say the least, when you consider the world of underground music in 1984. This was not only an obscure band, but an entire musical domain that existed far below the mainstream waterline. Then as now, the idea of comparing a little-known indie band to the Beatles seemed at best pretentious and at worst totally absurd.

Was it?

Twenty-three songs is a lot of music, but this is one the rare two-record sets that isn’t bogged down by its own overreaching or conceit. The scourge of most double LPs, back when there was such a thing, is they went on for too long — padded with live cuts, covers, and extras (heck even London Calling has its throw-aways). There’s no filler in Zen Arcade. Each and every song, from the shortest (44 seconds) to the longest (14 minutes), belongs exactly in its place.

Yes, that includes “The Tooth Fairy and the Princess.” The longest-named song on the record is probably the most easily dismissed. But it’s a clever little tempest of a song, littered with switchbacks and melodic explosions.

The album is best savored not as a CD — and for heaven’s sake not as a download — but in the old, cardboard-and-vinyl package. That’s a quintessentially record-snobbish thing to say, but unavoidable in this case, where each of the four sides is a distinct chapter with its own temperature and architecture.

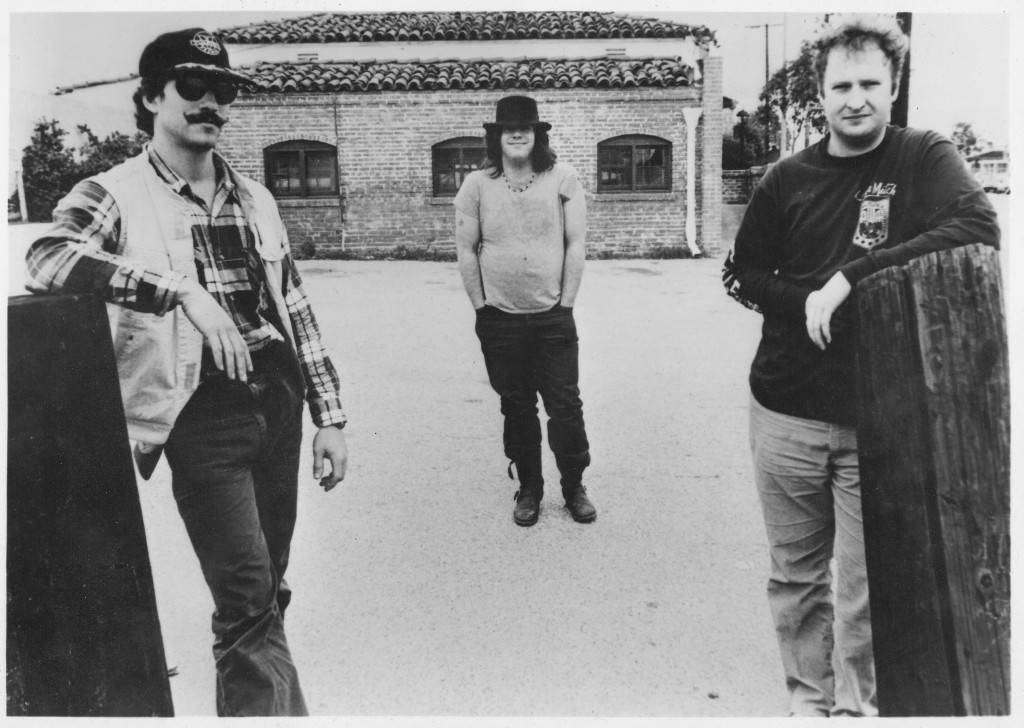

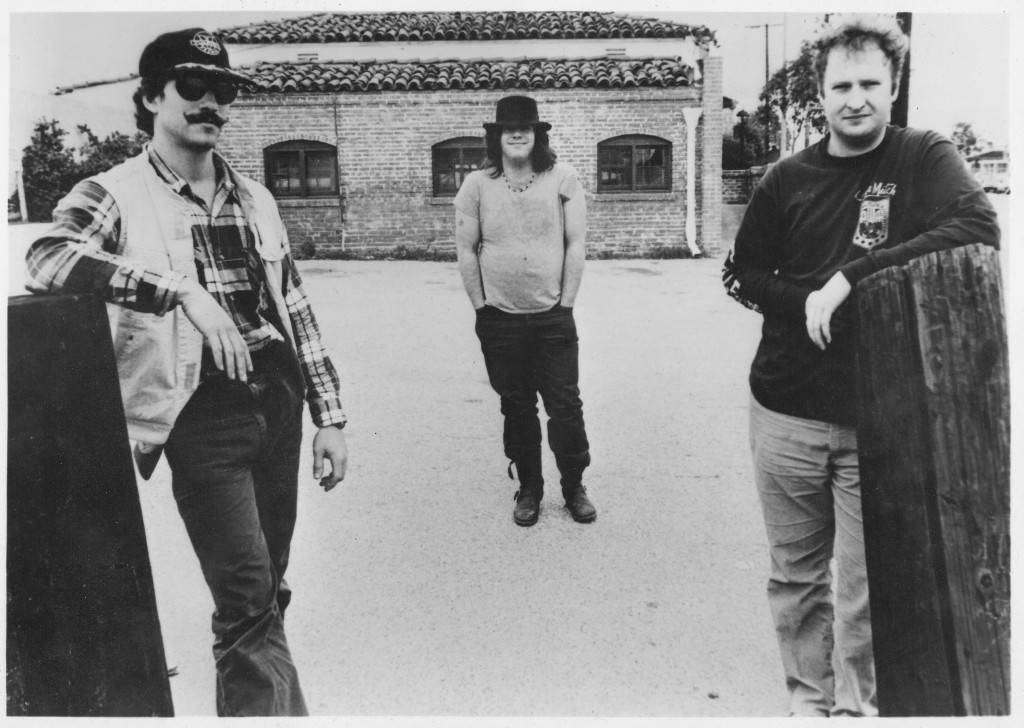

Greg Norton, Grant Hart, and Bob Mould, circa 1984.

Photo by Naomi Petersen.

Side one gets going without the slightest fuss, with the snap and kick of Bob Mould’s “Something I Learned Today,” eventually winding down with “Hare Krsna,” a booming, tambourine-backed instrumental (mostly).

The first time I heard “Hare Krsna,” sizzling over the stereo in a Boston area record shop not long after the album’s release, I remember the young clerk furrowing his brow, looking up toward the speakers and saying, “Somebody needs to write a dissertation about this song.” I couldn’t care less if they were plagiarizing a Bo Diddley riff; “Hare Krsna” is a mesmerizing, three-and-a-half minute cyclone of melodic chaos that still gives me the chills. Listen to Mould hitting the strings at time 0:44.

Side one alone is unforgettable. And there are three more to go. This is the ultimate workhorse album from the ultimate workhorse band, one so rich with sonic nooks and crannies that an in-depth listen leaves you not only battling tinnitus, but tired. So many changes from fast to slow, hard to soft, love to hate, all in perfect working sequence. And each side-break is a perfectly placed respite. I can’t think of a more brilliantly arranged opus than Zen Arcade. “The closest hardcore punk will ever get to an opera,” wrote David Fricke of Rolling Stone.

Indeed, this is a proverbial concept album — a musical story, in the spirit of the Who’s Tommy, allegedly describing the journey and tribulations of a young man. He leaves home, maybe joins a cult, maybe joins the Army…whatever. Alt-rock historians love reminding us about this, but you’re free to ignore it. Any lyrical backstory is incidental to the record’s impressiveness.

You’ll find a gamut of effects: acoustic guitar, chairs being thrown, waves breaking, whispers and chants. There’s even the breezy piano of “Monday Will Never be the Same.” (If Ken Burns ever directs a documentary about the history of alt-rock, the tinkling of “Monday” needs to be its backing theme.) Such eclectics are brave, maybe, for what was supposedly a punk album, but they never become maudlin or melodramatic. If you think today’s co-opted rockers are clever with the tempo card, shifting from tough to tender, check out Grant Hart’s “Never Talking to You Again,” a sing-along from side one done entirely in 12-string acoustic. “Heartfelt” is the word that jumps to mind, but it’s not the syrupy strum you’d hear nowadays. The song is biting and sharp — an attack. Ditto for “Standing By the Sea,” with Hart’s cathartic bellows set against bassist Greg Norton’s eerie thrum and the soothe of a crashing surf.

Back in ’84, the rock critic Robert Christgau chose Hart’s “Turn On the News,” from side four, as his “song of the year.” Christgau said many flattering things about Hüsker Dü, but that one was the gimmie pick, like saying the Concorde is your favorite airplane. It’s an easy song to like, but an even easier one to outgrow. If the album has a best song, it’s probably Bob Mould’s neo-pscychedelic “Chartered Trips,” the fourth cut off side one. (“Trips” is almost Mould’s single greatest work, topped only by his spectacular rendition of the Byrds’ “Eight Miles High,” released as a single just prior to Zen Arcade.)

Runner-up would be Hart’s “Pink Turns to Blue,” from side three. Officially the credits for this one list both Mould and Hart, but really this is Grant’s piece. He took all the hook and melody of his earlier masterpiece, “It’s Not Funny Anymore,” and sandblasted it into a haunting anthem of love, drugs, and death. The song is simply gorgeous — and a little bit terrifying. Score it ahead of “Chartered Trips” if you want. I’m not going to argue.

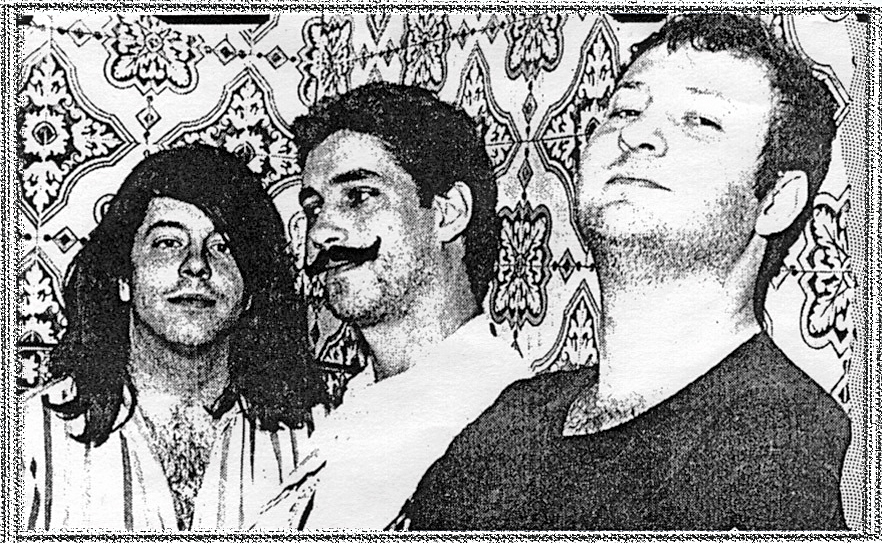

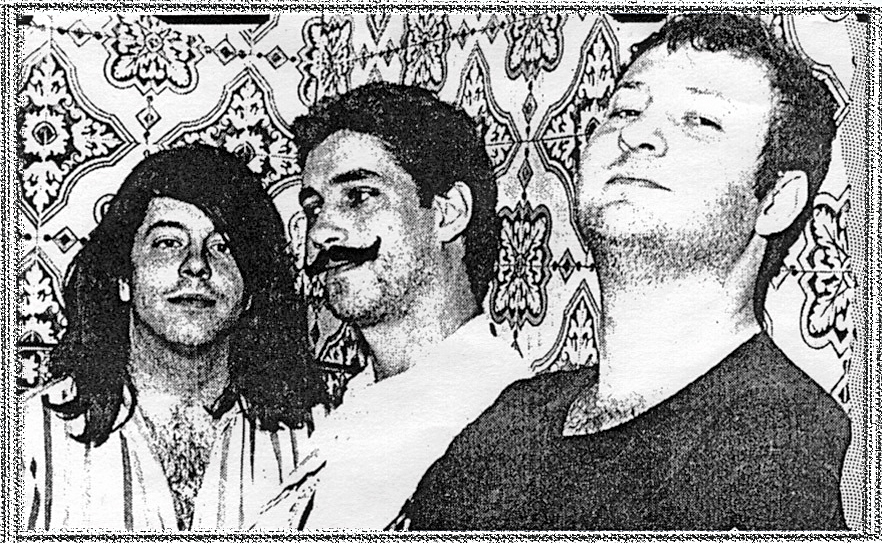

September, 1984, in the dressing room at the Channel.

Boston Rock magazine.

“Pink Turns to Blue” follows “One Step at a Time,” a brief piano time-out that, as much as anything else, allows the listener to catch his or her breath. The pregnant pause between the last note of “One Step” and the opening chord of “Pink” is like those one or two seconds between a lightning bolt and a thunderclap, and is one of the record’s strongest moments. It reminds me of the similarly unforgettable transition into “Sweet Jane” on the Velvet Underground’s Loaded album.

Before going further, I’m aware how this favorite songs thing can turn tedious pretty quickly. Grant Hart himself once offered a disclaimer: “People will always embrace different songs for different reasons,” he told me. “A song that might seem terrible filler, serving only to move the story along, will be someone’s favorite on the album. Bob and I were both responsible for those kind of songs.” Of my beloved “Hare Krsna” Grant claims that he was merely “furthering the story without adding much musically.” Hart felt similarly about some of Mould’s thrashier and more “hardcore” material.

To his point, not all of the album is easy to like and, depending on your ear and level of patience, the value of certain songs might not reveal itself for some time. For me it was twenty years before the first four songs from side two (Mould at his most furious) finally clicked. They’d always been so noisy and formless. Suddenly they weren’t. This was partly a context thing, maybe: the album, like wine, getting better not despite its age, but because of it. It took the overall shittiness of music in the 21st century to underscore the greatness of cuts like “Pride” and “The Biggest Lie” — mere footnotes in 1984. They’re awesome songs, at once explosive and subtle, but buried amidst so many other and perhaps better choices, that even the band’s most devoted fans tend to skip them over.

Similarly it was decades before I learned to appreciate “Broken Home, Broken Heart,” the second song on the album, for the gem that it is, tucked anonymously between “Something I Learned Today” and Hart’s “Never Talking to You Again,” with Norton’s bass stealing the show. And that a supposed punk rock album could jump from the fury of “Broken Home” to the acoustic beauty of “Never Talking”, without so much as a flinch, was a watershed in American music.

Though not entirely a surprise. Even at breakneck velocity there always was something ineffably refined and just, well, different about Hüsker Dü. If pressed to explain, one might break out 1982’s Everything Falls Apart EP. Amidst side one’s hypsersonic avalanche is Hart’s cover of Donovan’s 1966 hit, “Sunshine Superman.” Playful, perhaps, on the face of it, until you hear how un-ironic the remake is, without a note’s worth of smirk or parody. This wasn’t a joke.

Later, on his solo tours, Bob Mould would often play acoustic versions of some of the hardest and fastest Hüsker Dü songs — cuts like “In a Free Land” or “Celebrated Summer” — and the results were startlingly pretty. That’s just not going to work if you’re Black Flag, the Dead Kennedys or Bad Brains. Or Nirvana. Run even the noisiest Hüsker song through a centrifuge and something elegant reveals itself.

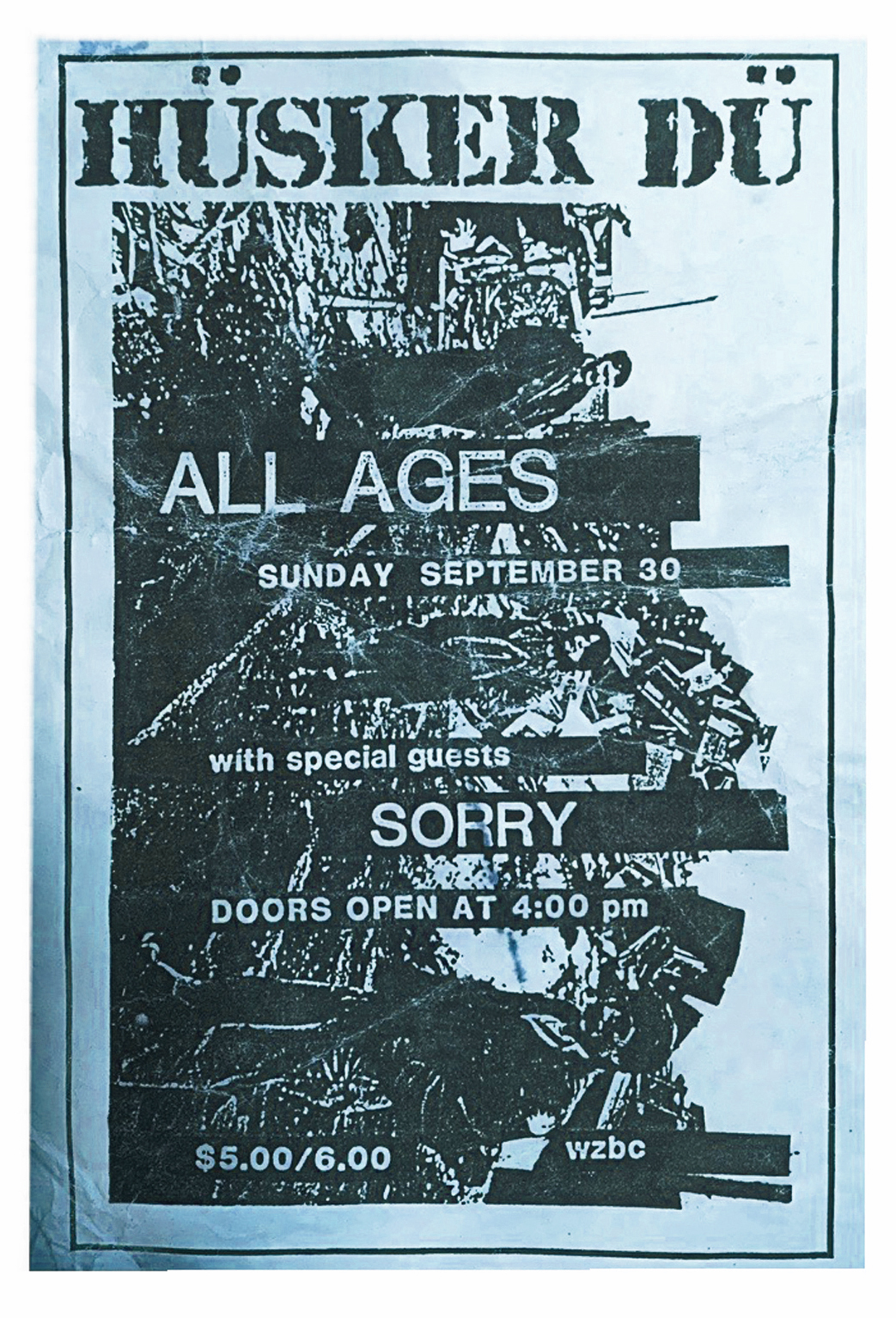

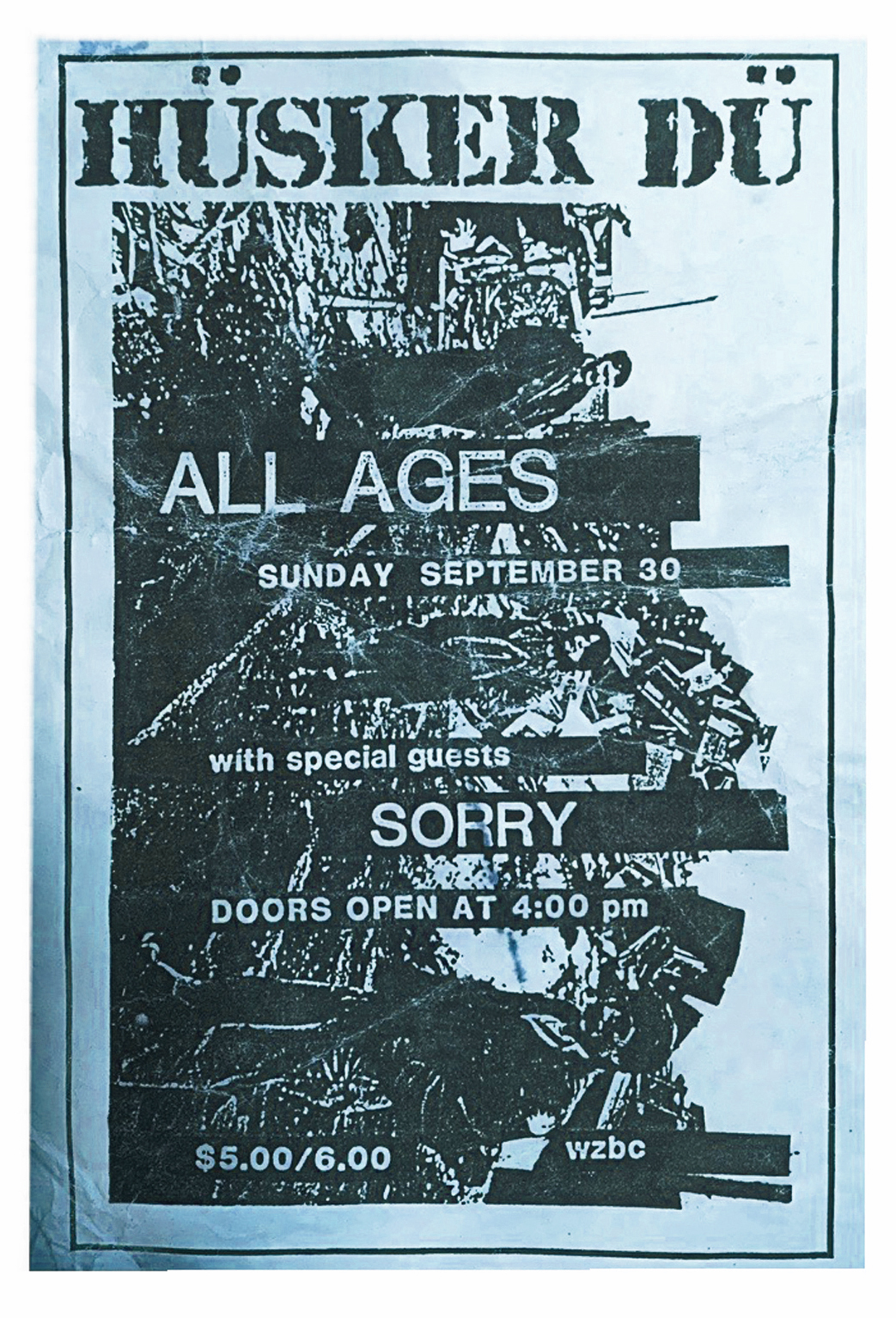

Concert flyer, Boston, 1984. Author’s Collection.

With its blend of hippie love and hard rock thunder, Zen Arcade would, in a way, finish the job that the Velvet Underground and even the Beatles had tinkered with earlier. But while the blending of power/pop extremes was nothing new, the Hüskers pulled it off in a way that was never gimmicky (not until their lazy cover of “Love is All Around,” the Mary Tyler Moore Show theme, in 1986), and, most remarkably, did so on such terrain –- the American hardcore punk scene –- where nobody expected it or even believed it possible.

“A strenuous refutation of hardcore orthodoxy,” as Michael Azerrad puts it in his book, Our Band Could Be Your Life: Scenes from the American Indie Underground, 1981-1991. “Zen Arcade was the final word on the [punk rock] genre, a scorching of musical earth. The album wasn’t only about Hüsker Dü coming of age — it was about an entire musical movement coming of age.”

Zen Arcade is the album Nirvana and its contemporaries only wish they could have made: intelligent, clamorous, and hashing out more torment and passion in four sides than all the grungers and headbangers since. All without a hint of heavy metal pretension: to think anyone could concoct a fourteen-minute bombast of guitar leads and layered distortion — “Reoccurring Dreams,” side four — and have it not come out self-indulgently.

All right, maybe it’s a little self-indulgent. But listen carefully enough and you’ll learn that “Dreams” can be parsed into six or seven subsections, each of them breaking through to the next, right in the nick of time. The song is long, but never wears out its welcome. It belongs there, in its entirety. An epic album deserves an epic close.

And when the 40-second whine at the end of “Dreams” is at last pinched off, the album burning to a close in a congealed, numbing squeal, the silence that follows is palpable, as dramatic as any of record’s loudest moments. Only then, as your senses regain their composure, is it apparent that your notions of punk rock are changed forever.

But not everybody, however — not even Grant Hart — has openly accepted such lavish praise. Hart once described Zen as the album that fans “tend to wear on their sleeves.” Did he mean people like me? Have I been too sentimentally fond of it for some reason?

“The impact of Zen Arcade on the Zeitgeist is hilarious to me,” said Grant. “Hilarious in the almost alchemical-mechanical way it has been embraced by true music fans and hipster-flipsters alike. When somebody states that Zen is their favorite LP, I get the notion to ask why. As we move further from the time it was released, it seems I get more honest answers.”

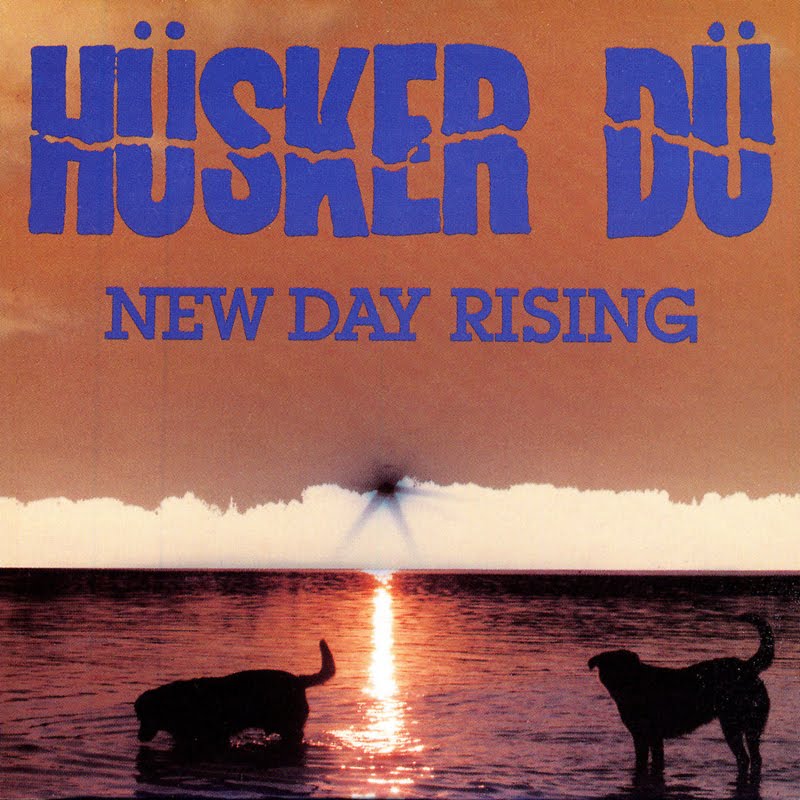

My honest answer is that I like it the best because it sounds the best, and by the sum of its parts it is the best. And for the record, Zen Arcade is not my “favorite” Husker Dü LP. New Day Rising is my “favorite” Husker Dü LP. But that’s getting personal. When you look at it objectively, Zen is the better and more profound of the two.

Norton, Hart, Mould, circa 1983.

Photo by Daniel Corrigan.

Hüsker Dü were nothing if not prolific. A mere six months after Zen Arcade came New Day Rising, which woke the country from its winter freeze in January, 1985. These are two best albums of the 1980s, and they appeared within six months of each other!

Eight month’s after that came “Flip Your Wig,” the band’s last album before signing with a major label. Flip suffers from terrible production but is nonetheless memorable, highlighted by Hart’s pièce de résistance, “Keep Hanging On.” Prior to Zen, meanwhile, was Metal Circus, a brilliant seven-song EP from 1983. Together, these four records represent, easily, the most potent 1-2-3-4 punch in the annals of indie music. All released in the astonishing space of less than two years. That’s simply incredible.

In 1986 and 1987, having moved from SST to Warner Brothers, Hüsker Dü released two disappointing and anticlimactic albums,”Candy Apple Gray” and “Warehouse: Songs and Stories.” I’m unsure which of these two records annoys me more, but neither, really, has much place in this conversation. “Candy Apple Grey” does well at the start and finish — I’ve always loved the gothic guitar squall of the opener, “Crystal,” as well as the closer, “All This I’ve Done For You” — but the rest is flyover country, including Bob Mould’s abominable “Too Far Down,” which has to be the ugliest song he ever recorded.

With Warehouse, it’s as if they took Zen Arcade placed it on a table in front of them and said, “Okay how can we ruin this?” Like Zen Arcade, it’s a double LP. Unlike Zen Arcade, it’s bloated with filler. I’ll always love “Back From Somewhere” and “She’s a Woman (and Now He Is a Man),” but the plodding, uninspired likes of “Ice Cold Ice,” “You’re a Soldier,” and too many others, anchor this one at the bottom of the Hüsker canon.

Bob and Grant had their power struggles, but as a songwriting tandem their talents were wonderfully complementary — think Strummer and Jones, or McCartney and Lennon. This was much of what made the band so great. By the time “Warehouse” warbles to a close, clearly this synchronicity is unraveling. Hart, at least, holds his own on this record, while Mould’s songs are overextended and lazy. Depressing as it was, you could say that Hüsker Dü broke up exactly when it needed to.

Meanwhile, unless I’ve missed something, none of the big music magazines or websites gave Zen Arcade so much as a mention on its 20th, 15th, or 30th birthdays. Some years ago Spin awarded it the number four spot on its ranking of the hundred best-ever “alternative” records, and Rolling Stone, in a manic best-of-the-80s list, once gave it lip service at number 33. But what since then? Instead we have bands like Green Day winning Grammys.

For that matter, do younger music fans have any sense of what the 1980s truly were like? This was the richest and most innovative period in the whole history of independent music, but rarely is it acknowledged as such. As popular culture has it, serious rock music skipped the 80s entirely. When pundits do take the decade seriously, we tend to see the same names over and over. It’s both frustrating and unjustified that Hüsker Dü never developed the same posthumous cachet that others of their era did. Like the Replacements, for example, or Sonic Youth. Hüsker Dü could run circles around either of those two, but never became “cool” in quite the same way.

I suppose it’s due to an absence of what you might call sex appeal. To say that Hüsker Dü never cultivated any sort of image, in the usual manner of rock bands, is putting it mildly. For one, they never looked the part. These were big, sweaty, chain-smoking guys who, it often seemed, hadn’t shaved or showered in a while. Norton, trimmest and most dapper of the threesome, wore a handlebar mustache many years before such things were trendy among hipsters. It wasn’t cool; it was odd. And not until their eighth and final album did the band included a photo of itself on an album cover (the scratched-out images on Zen Arcade notwithstanding). It was a small, back-cover pic that almost feels like an afterthought, or something the record company made them do.

This modesty, for lack of a better description, was for some of us a part of what made Hüsker Dü so special. But it has hurt them, I think, in the long run. (As has the fact that only the band’s final two albums are available on iTunes. But that’s another story.)

The idea that the Replacements (much as I loved their debut album, which I consider the best garage-rock record of all time, and which includes a shout-out called “Somethin’to Dü”) were in any way a better or more influential band than Hüsker Dü is too absurd to entertain. Meanwhile the beatification of Sonic Youth, maybe the most overrated outfit of the last forty years, goes on and on. Not long ago Kim Gordon got a profile in the New Yorker. I’m still waiting for one of the writers there to devote a story to Bob Mould.

Or better yet, to Grant Hart. Twenty-five years, more or less, that’s how long it took me, to realize that it was Grant, not Bob, who was the more indispensable songwriter and who leaves the richer legacy. In the old days it was trendy to claim that Grant was the real genius behind Hüsker Dü. You’d be at a party and some asshole would say, “Those guys would be nothing without that drummer.” I’d always scoff that off. The mechanics of the band, for one, made it difficult to accept: Grant was the drummer, after all, and drummers are never the stars. Meanwhile there was Bob, right at the front of the stage with that iconic Flying-V. But those assholes were on to something.

That shouldn’t be an insult to Mould. Not any more than saying John Lennon was a better songwriter than Paul McCartney. Both were brilliant. But when I flip through the Hüsker canon, I can’t help giving Hart the edge. On New Day Rising, for instance, Mould gave us “I Apologize” and “Celebrated Summer.” But Hart gave us “Terms of Psychic Warfare” and “Books About UFOs,” two of the most electrifying songs of the 80s. “It’s Not Funny Anymore,” “Diane,” “Pink Turns to Blue,” the list goes on. Hart’s “She’s a Woman (And Now He is a Man”) from the often intolerable Warehouse album is, to me, a classic sleeper and the most under-appreciated Hüsker song of them all.

His solo work, too, was at least as robust as that of Mould. Songs like “The Main” and “The Last Days of Pompeii” are as good or better than anything Mould has given us post-Hüsker. But while Mould went on to some notoriety and commercial success, Hart labored in comparative obscurity. This was always irritating and unfair.

But Grant, maybe, was all right with this. “I have always based my movements on those of fugitives or criminals,” he once said to me. “The less attention you attract, the freer you remain! I wish to be an artist, not a celebrity.”

Hüsker Dü in 1986. Photo by Daniel Corrigan.

Related Story:

HAPPY BIRTHDAY TO THE (SECOND) GREATEST ALBUM OF ALL TIME

POSTSCRIPT, ASTERISKS AND MISCELLANY…

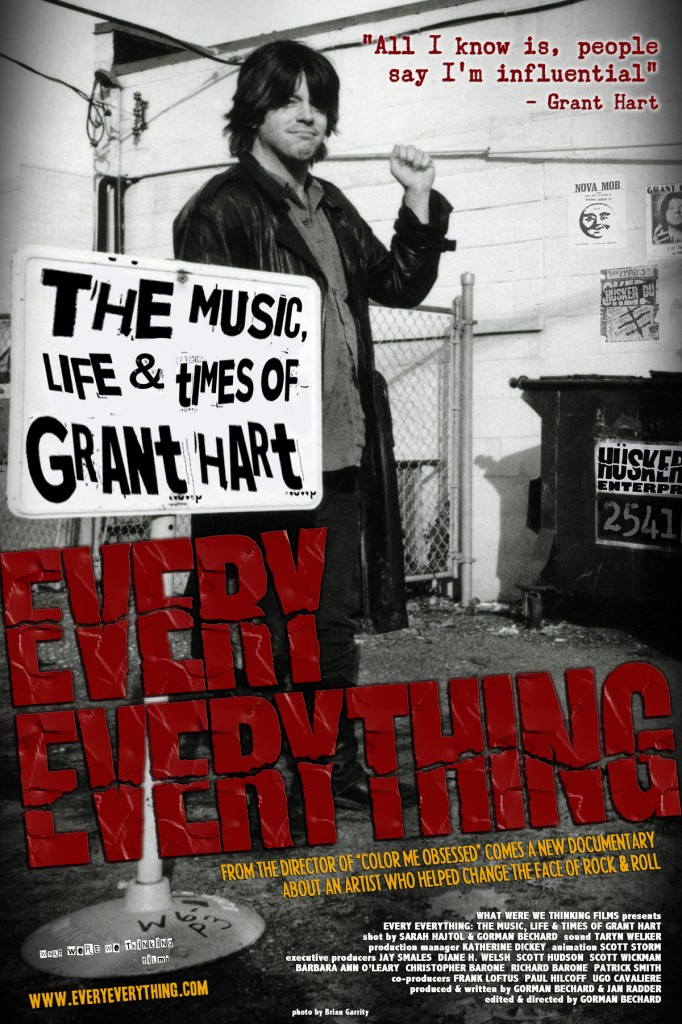

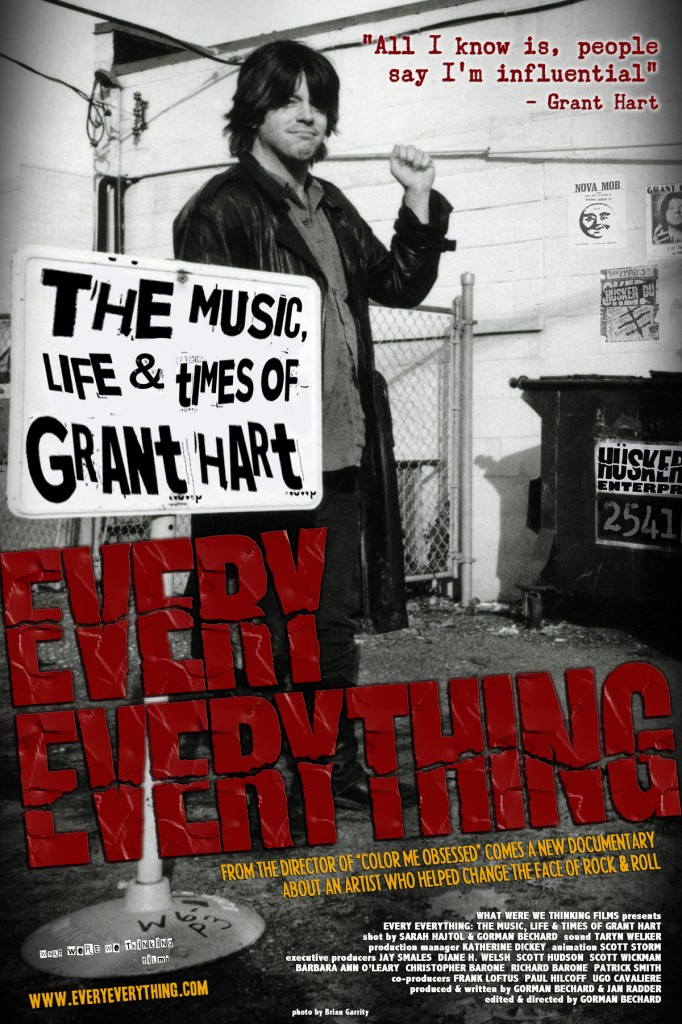

Grant Hart died in September, 2017. A few years ago, filmmaker Gorman Bechard released a movie about him. “Every Everything” is 93 minutes of Grant — and only Grant — proving himself to be one of the more oddly captivating storytellers you’ll ever have the pleasure of listening to.

Bechard had previously interviewed Grant for “Color Me Obsessed,” his film about The Replacements, and was taken with him. “Grant is one of the most influential musicians ever,” said Bechard at the time. “Beyond that, he’s as smart and funny as anyone on the planet.”

You may not be familiar with Hart, but he was among the most important songwriters of our time, and “Every Everything” is a brave and absolutely necessary tribute to one of the unsung heroes of modern music. Click the picture for more info…

— The one song I would probably have pruned from Zen Arcade is “Dreams Reoccurring,” the noisy little instrumental from side one. You’ve got the fourteen-minute version later on; do we really need this miniature version too? And the fact that “Indecision Time” isn’t so great either… it creates kind of a dead spot on the first side. In its place I’d have put “Some Kind of Fun,” one of the outtakes.

— The greatest concert I ever attended was an impromptu Husker show at a place called Harvey Wheeler Hall, in Concord, Massachusetts, on December 30th, 1984. It was a last-minute gig arranged by David Savoy, a Concord native who also was the band’s manager at the time (and whose suicide a few years later was partly responsible for its breakup). There was no stage; the band set up on the floor of what, in my memory, was a simple classroom. There were fewer than a hundred people there, and we stood or sat cross-legged. The set ended when Grant cut his finger on a cracked drumstick during a cover of the Beatles’ “Ticket to Ride.” My best friend at the time, Mark McKay (who later became the drummer for the post-hardcore band Slapshot), gave him a band-aid. When it was over we went backstage, as it were, and chatted a while with the band.

— A few years ago, Paul Hilcoff, the curator of the painfully exhaustive Hüsker Dü fan site, mailed me a compact disc recording of that entire concert. I had no idea there was one. What a startling feeling it is to discover, many years on, that a recording exists of one of your most cherished memories. Except, the CD still sits on my bookshelf, as yet unlistened-to. One of these days I’ll summon up the courage to actually play it. Listening to that recording, provided I’ve got the emotional muster, will be the closest I ever get to time travel.

— I once played Frisbee with Bob Mould. June 21, 1984, it was, prior to a show in Easthampton Massachusetts. There were four of us playing: me, Bob, a local Boston fanzine writer named Al Quint, and the aforementioned McKay.

— I once got to meet and shake hands with Bob Mould’s parents. It was that same summer of ’84, in Rhode Island. Mom and dad were touring the country, stopping in on the band’s performances. Bob himself introduced me to them.

— Greg Norton once sat patiently backstage while I peppered him with inane questions for a fanzine article I was writing.

— It was Grant, though, who was always the friendliest and most approachable of the three. I remember a night, between sets down at The Living Room in Providence, chatting with him in the parking lot. He was snacking on slices of cheese, when a stray dog came ambling over. Grant shared his cheese with the dog, holding up small bits of it, ever higher, making the dog jump for them.

— That was the same show in which Mould, rushing toward the stage for an encore, smashed his head against a ceiling rafter so hard that you could hear it from the parking lot. I have a feeling he remembers that.

GREATEST HITS, MOULD:

1. Eight Miles High (single)

2. Chartered Trips (Zen Arcade)

3. I Apologize (New Day Rising)

4. Gravity (Everything Falls Apart)

5. Crystal (Candy Apple Grey)

6. Real World (Metal Circus)

7. Makes No Sense at All (Flip Your Wig)

8. Celebrated Summer (New Day Rising)

9. Perfect Example (New Day Rising)

10. All This I’ve Done For You (Candy Apple Grey)

GREATEST HITS, HART:

1. Keep Hanging On (Flip Your Wig)

2. Terms of Psychic Warfare (New Day Rising)

3. Pink Turns to Blue (Zen Arcade)

4. Books About UFOs (New Day Rising)

5. It’s Not Funny Anymore (Metal Circus)

6. She’s a Woman [And Now he is a Man] (Warehouse: Songs and Stories)

7. Standing by the Sea (Zen Arcade)

8. Diane (Metal Circus)

9. The Girl Who Lives on Heaven Hill (New Day Rising)

10. Sunshine Superman (Everything Falls Apart)

Now if you’ve stayed with me this far, chances are you’re a pretty big Hüsker fan who won’t mind if I push things an obsessive step further. For you I present the following addendum. You’ve been warned:

I was looking at some photos of Hüsker Dü in their heyday, circa ’84 or ’85. These guys were, to put it one way, well-fed. Greg always kept himself trim and dapper, but Bob and Grant weren’t going hungry, that’s for sure.

It’s only fair, then, that we should revisit the Hüsker discography, making note of various song titles as they should have appeared. That is, with a gastronomical theme…

There’s little on Land Speed Record or Everything Falls Apart to cook with, so let’s start with Metal Circus. Here, Bob sets the table with “MEAL WORLD,” then takes his place in the “LUNCHLINE.” Grant tells us “I’M NOT HUNGRY ANYMORE,” but later opts for some delicious “STEAK DIANE.”

Zen Arcade is a veritable buffet line of fatty faves: Bob cooks up some “CHARRED TIPS.” Later he orders some “PRIME” down at the “NEWEST EATERY.” He’s got a sweet tooth for “THE BIGGEST PIE.” Alas, it’s a “BROKEN COOKIE, BROKEN HEART.” Grant warns that he’s “NEVER COOKING FOR YOU AGAIN,” yet later we find him “STANDING BY THE STOVE,” dreaming of that moment when “BEEF TURNS TO STEW” (“…waiters placing, gently placing, napkins round her plate.”) This is a very long album, and indigestion sets in by the end of side four, closing with the epic, flatulent jam, “REOCCURRING BEANS.”

Prior to Zen Arcade, you might remember, came the Huskers’ famous 7-inch single — its cover of the Byrds’ — or is it Birds’ — classic, “EGGS PILED HIGH.”

On New Day Rising, Grant tells us about “THE GIRL WHO WORKS AT THE BAR & GRILL,” followed on side two by the sugary “BOOKS ABOUT OREOS.” Bob serves up a “CELEBRATED SUPPER.”

Flip Your Wig is, let’s just say, a little thin, though Grant gives us a cooking lesson with “FLEXIBLE FRYER.”

On Candy Apple Pie… er, Gray … again its Grant with the big appetite. His two meaty singles are, “DON’T WANT TO KNOW IF YOU’RE HUNGRY,” and “HUNGRY SOMEHOW.”

The band’s final course is the delectable double LP: Steakhouse: Songs and Stories. Bob sings of “THESE IMPORTED BEERS,” before going gourmet on the plaintive “BED OF SNAILS.” Alas, he has “NO (DINNER) RESERVATIONS.” Grant snacks on some “CHARITY, CHASTITY, PEANUTS AND COKE,” and reminds us that “YOU CAN COOK AT HOME.”