Letter From Chernobyl

February 25, 2022

THE SITUATION in Ukraine brings me back to my visits to the capital city, Kiev, some years ago, when my airline was still flying there.

Kiev really surprised me. It was green, hilly, with parks and museums and onion-dome churches. Nothing of the bleak, Soviet-looking city I expected. Our layover hotel was the Premier Palace, an expensive place done up in chandeliers and marble. It was the kind of hotel in which you always felt underdressed. But it had an edge to it — that unmistakable vibe of post-Soviet decadence. There was a strip club on the sixth floor.

Of the various day trips available in and around Kiev, none was more extraordinary than the chance to tour Chernobyl, only two hours away by car.

In April of 1986, reactor four at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant exploded, sending plumes of radiation across Europe in what is still, by far, history’s worst nuclear accident. Prevailing winds saved Kiev from disaster, carrying the fallout in the opposite direction, north into Belarus. From there it diffused across northern Europe.

To this day, a 30-kilometer “Exclusion Zone” surrounds the site, accessible only to researchers, temporary workers, and a small number of villagers — most of them senior citizens — that the Ukrainian government allows to live there. And, believe it or not, to tourists.

I took one of those tours in October of 2007. At the time of my visit, a full-day Chernobyl excursion cost about $250. It included transportation to and from the site, plus all the admission formalities — and a radiation scan on your way out. The photographs below are from that day.

A guide accompanied us the entire time, but we were more or less free to wander as we pleased. We had the site almost entirely to ourselves, walking through apartment blocks, kindergarten classrooms, a high school, a hotel.

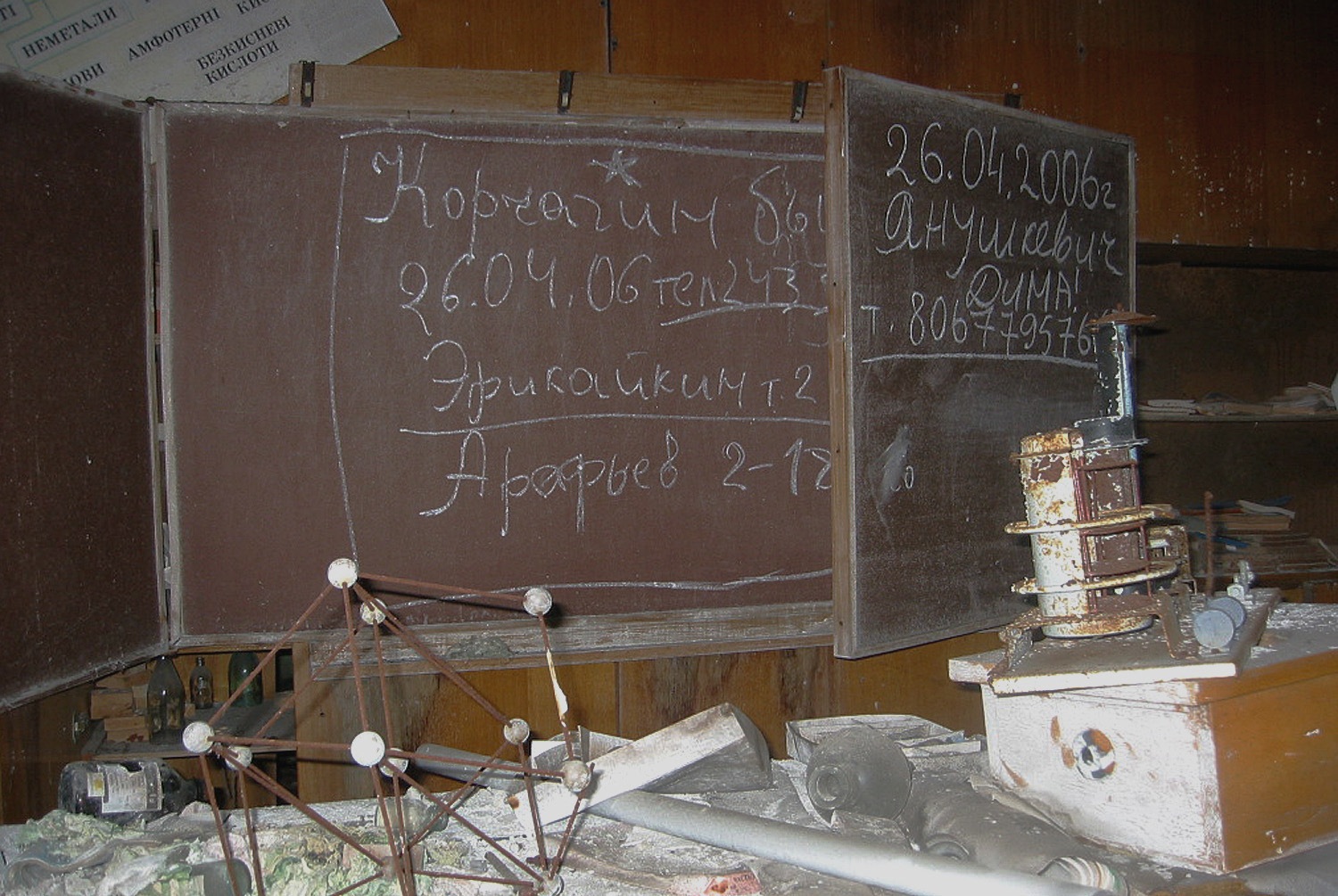

I have not captioned the pictures. They more or less speak for themselves. Most of them were taken in Pripyat, the abandoned city inside the Exclusion Zone that was once home to 50,000 people. The entire population of Pripyat was forced to flee, leaving everything behind. It exists as a sort of Soviet time capsule, a bustling city left in suspended animation, complete with hammers, sickles, and no shortage of radioactive detritus that was once the stuff of regular, everyday lives: kids’ toys, a ferris wheel, a classroom chalkboard. It’s these everyday items that leave the most lasting impression — a perversion of normalcy that drives home the magnitude of the tragedy.

When the reactor blew, Soviet helicopters dumped sand and clay over the exposed core, and later the building was encased in thousands of tons of concrete — a structure that become known as “the sarcophagus.” In the photo above, our guide aims his dosimeter at the sarcophagus. The reading you see on the machine is about sixty times normal background radiation. We were allowed to remain here only for about ten minutes.

I should note that reactor four no longer looks like this. In 2016, authorities completed the installation of a mammoth protective dome, concealing the remains within a 25,000-ton shell, made of steel, that looks like a cross between a football stadium and an airship hangar. What you see today is a much more sterile, less jarring aesthetic.

ALL PHOTOGRAPHS BY PATRICK SMITH

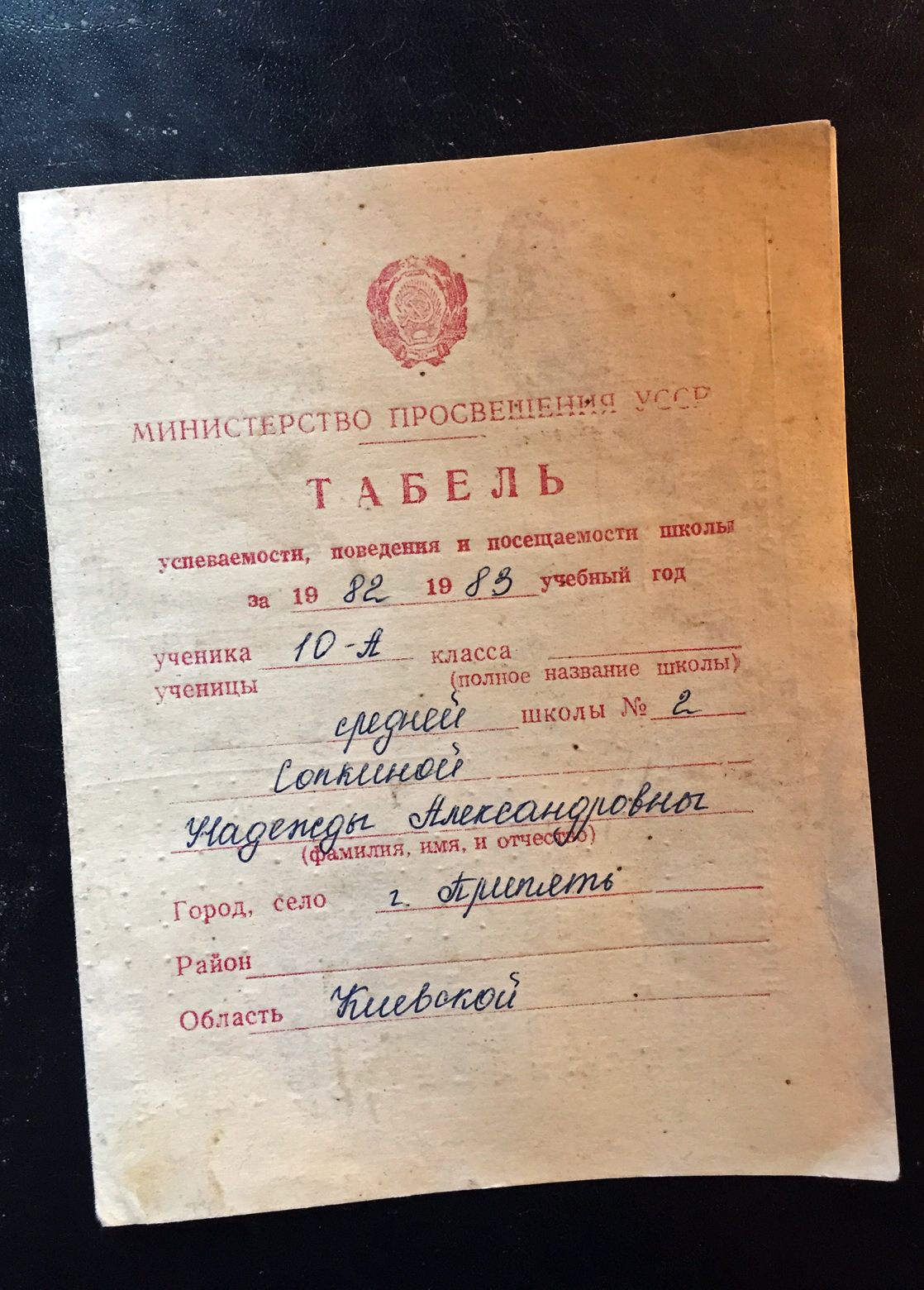

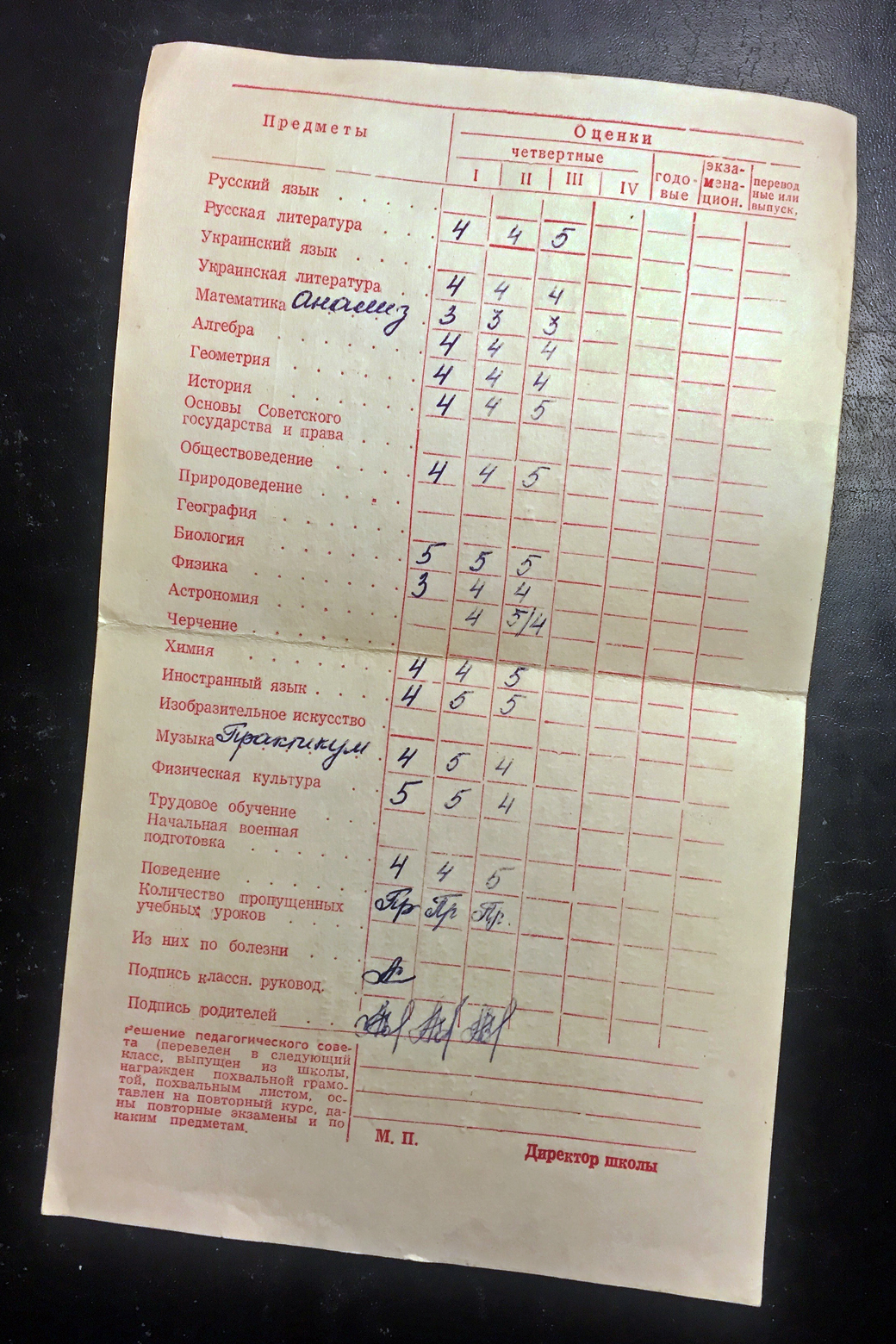

The items below are souvenirs, I guess you’d have to call them, scavenged from Pripyat. Among them are a 1984 copy of Pravda, the Soviet state newspaper; some vintage postage stamps, and what appears to be a school report card, found inside the Pripyat high school. Perhaps some Ukrainian speakers out there can help translate some of this. I’d love to know more about the report card — names, dates, anything.

The bottom shot is from a roll of exposed film, found on the floor near the high school gymnasium.

Hopefully these items haven’t turned my apartment radioactive.

Two decades before my trip to Chernobyl, I’d been to the Soviet Union, visiting both Moscow and Leningrad (as St. Petersburg was known at the time). This was March of 1986, about a month before the reactor accident. Among the highlights of that trip were my flights aboard Aeroflot. I got to ride a Tupolev Tu-154 from Moscow to Leningrad, and then a Tu-134 from Leningrad to Helsinki.

Apple juice. I remember the Aeroflot flight attendants serving plastic cups of apple juice.

It dawns on me, too, that my travel habits are at times decidedly macabre. In addition to my trip to Chernobyl, I’ve been to the Auschwitz-Birkenau complex in Poland, and to the various Killing Fields sites around Phnom Penh, in Cambodia. Some people make a hobby of such trips. They call it “disaster tourism,” or some such. Everyone has their own motives, but I like to believe there can be a deeper purpose to these visits than morbid thrill-seeking.