When is a Country Not a Country?

Border Crossing Conundrums for Travelers

October 23, 2024

Port au Prince, Haiti, 1999

“Sorry, it’s too dangerous,” says the driver.

To the best of my knowledge and experience, Port-au-Prince is the only place in the world this side of eastern Ukraine where a cabbie will refuse a twenty-dollar bill to take an American into town for a quick drive-through tour.

With nothing else to do I wander the apron. Behind our dormant jet a row of scarred, treeless hills bakes in the noon heat, raped of their wood and foliage by a million hungry Haitians. The island of Hispaniola is shared in an east-west split between Haiti and the Dominican Republic, and the border between these countries is one of the few national demarcations clearly visible from 35,000 feet — the Dominican’s green tropical carpet abutting a Haitian deathscape of denuded hillsides the color of sawdust.

In front of the terminal, men ride by on donkeys and women balance baskets atop their heads. Somebody has started a cooking fire on the sidewalk. Haiti is the poorest country in the western hemisphere, and there’s more squalor along the airport perimeter than you’d see in the most run-down parts of Africa.

I notice a pair of large white drums being unloaded from our airplane. I ask a loader if he knows what the barrels contain, wondering what sort of nasty hazmat we’d just brought in. A forklift carries them to a corner of a ramshackle warehouse, and three skinny helpers pry off the heavy plastic lids. What’s revealed is a tangled white mass of what appears to be string cheese floating in water. A vague, quiveringly rotten smell rises from the liquid.

The forklift driver sticks in his hand and gives the ugly congealment a churn. “For sausage,” he answers. What we’re looking at, it turns out, is a barrel full of intestines — casings bound for some horrible Haitian factory to be stuffed with meat. Why the casings need to be imported while the meat itself is apparently on hand, I can’t say, but somebody found it necessary to pay the shipping costs and customs duties to fly a hundred gallons of intestines from Miami to Port-au-Prince.

THE SEGMENT ABOVE is from a book I’ve been pretending to write. It describes an afternoon several years ago, when I was a cargo pilot for DHL. The setting is the Port au Prince airport in Haiti — a country I’ve never been to.

Oh sure, I’ve flown into to the Port au Prince airport once or twice. But just the same, so far as I’m concerned, seeing that I never set foot outside the terminal, I have not been to Haiti.

The issue here is what, exactly, constitutes a visit to another country. Making that determination can be tricky, and those who travel a lot will sometimes wrestle with this quandary. When your plane stops for refueling or you spend the evening at an airport hotel… does that count?

Where to draw the line is ultimately up to the traveler; it’s more about “feel” than any technical definition of a border crossing. But there should be a certain, if ineffable standard — something along the lines of that you-know-it-when-you-see-it definition of pornography.

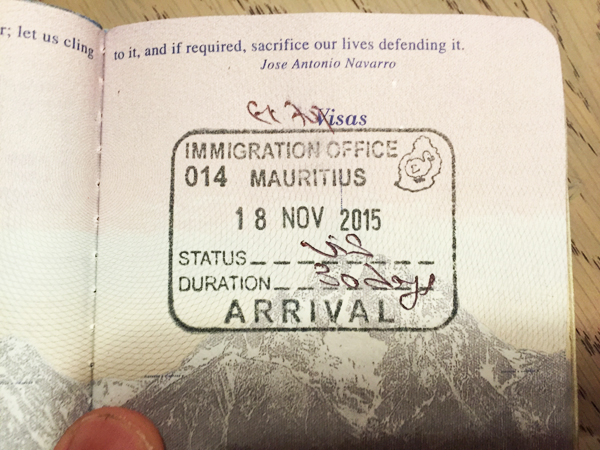

According to my own criteria, a passport stamp alone doesn’t cut it. At the very least, a person must spend a token amount of time — though not necessarily an overnight — beyond the airport and its environs. On the pin-studded map that hangs in the dining room of my apartment, there is no pin for Haiti.

Other cases, though, are more subjective. For instance, traveling once between Germany and Hungary, I spent several hours riding a train through Austria. We pulled into Vienna in the middle of the night and sat for six hours. At sunrise we headed out again, trundling across the Austrian countryside toward Budapest. Certain people might consider that enough, but as with Haiti there’s no Austria pin on my map. I saw towns, cars, people… but all through the window of a train, never touching soil. Doesn’t count.

On the other hand, I have been to Liberia. I used to fly a regular route there from Accra, Ghana, and our flights would lay over for a few hours at Liberia’s international airport, known as Roberts Field. One time I hired a driver to take us out for a mini-tour of the nearby area. We never spent the night, but I walked through villages, saw people, took pictures. Liberia gets a pin.

As does Qatar, though I spent a mere three hours in Doha, driving around at night, between flights, on a tour provided by Qatar Airways.

Sometimes the country itself is what muddles things up. Consider the world’s various territories, protectorates, self-governing autonomous regions, occupied lands and quasi-independent nations. Yeah, I know, Vatican City is a sovereign state, politically speaking. But in practical terms, is it really? When I tally up the countries I’ve visited, I can’t bring myself to include it.

And let’s not begin to assess the countless atolls, archipelagos, and assorted tiny islands scattered throughout the oceans. If a citizen of Japan visits Guam, has he been to the United States? In one sense, sure. In another, perhaps more accurate sense, he’s simply been to Guam — neither genuine U.S. turf nor a country unto itself. You can make a similar argument with Bermuda, Tahiti, and elsewhere. And let’s not get started with Tibet, or Palestine. Sometimes, maybe, there is no country.

Together these things can make it impossible to provide a wholly accurate answer when asked how many countries you’ve traveled to. It depends. For me the number is ninety-eight. Or thereabouts.

Of course, that’s only important if you’re the sort who keeps track of such things. Travelers are known to hold “passport parties” upon reaching certain milestones – a 50th, 75th, or 100th country. In the eyes of some, country-counting cheapens the act of travel by emphasizing quantity over quality, but maybe that’s sour grapes.

PHOTOS BY THE AUTHOR

A version of this post originally appeared in the magazine Salon.