Me and My Sharpie

October 24, 2022

LOTS GOING ON in the aviation world, beginning with the fact that I’ve retired my yellow highlighter. That’s right, I no longer carry a yellow highlighter as part of my pocket-flap ensemble of necessary cockpit gear.

Some months ago, you might recall, I talked about how, in the pocket of my (wrinkled) polyester pilot shirt, you’ll always find three things: a ballpoint pen, a highlighter, and a red Sharpie. The highlighter I’d use for marking up the flight plan. I’d go through it page by page, striking the important parts in yellow: the flight time, the alternates, the dispatcher’s desk number, the airport elevations, deferred maintenance items, ETP coordinates, etc.

Well, now that our flight plans have gone digital, there’s not much call for this. We still carry a hard copy version of the flight plan, it’s true, but at this point it’s just a backup, rolled and stuffed into a cubby hole near the center pedestal. And you can’t use a highlighter, really, on an iPad.

What I’m not letting go of, on the other hand, is my beloved red Sharpie.

The Sharpie is my tool for what we’ll call high-emphasis tasks, the most critical of which is putting my initials on the cap of my water bottle, to keep other pilots from drinking from it (there are sometimes four of us up there). I also use it for my scratch-pad notes. When I’m in the first officer’s seat on the 767, there’s a clipboard along the bottom ledge of the window, just to my right. I keep a folded piece of paper there on which I jot down various quick-reference info — a distillation of bullet points from the flight plan.

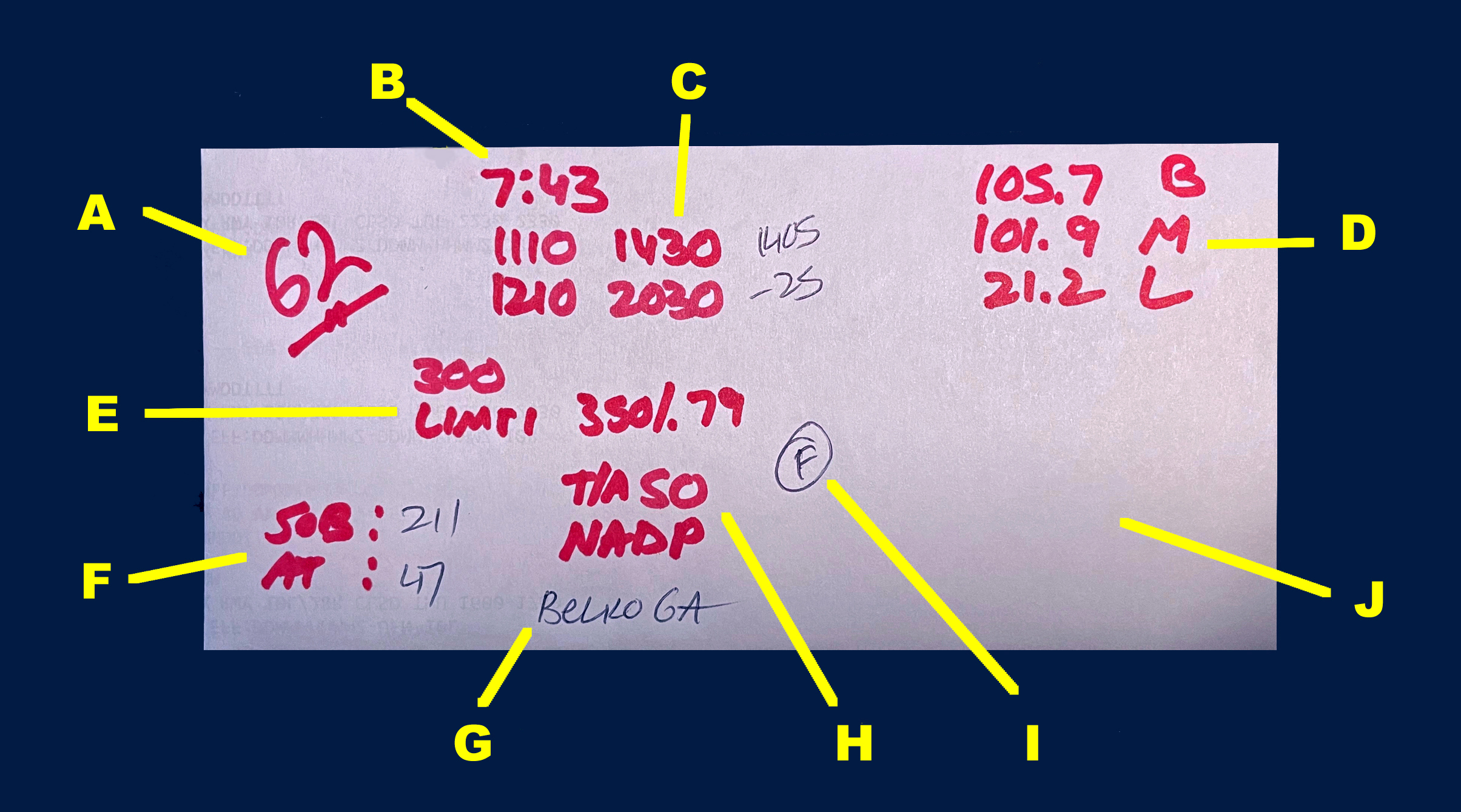

I prepare the sheet prior to departure, while still at the gate, as part of my preflight prep. The photo below is an example of a sheet used on a flight from Europe to the U.S. Here’s what it all means…

A. This is the flight number.

B. Planned flying time, wheels up to wheels down.

C. Arrival and departure times. Scheduled times are in red, in both local and UTC (Greenwich time). In this case, we’re scheduled to depart at 1110 local, and arrive at 1430 local. Or 1210 and 2030 respectively, in UTC. The addendum in pen, added after departure, is our arrival time based on when we actually took off. Today we’ll be 25 minutes early.

D. Fuel figures, in thousands of pounds. Block (B), minimum (M), and landing (L). Block fuel is our amount at pushback, which today will be 105,700 pounds. Minimum fuel is the lowest amount with which we’re permitted to commence the takeoff roll, in accordance with a slew of rules that we’ll save for another time. Landing fuel is our anticipated total at touchdown.

E. “300” is our initial expected flight level (altitude). That is, 30,000 feet, or “flight level three-hundred.” Below it I’ve written the name of the entry fix of our anticipated oceanic track, as well as our intended crossing altitude and speed. “LIMRI” is the fix name, and we hope to cross the Atlantic at 35,000 feet and Mach .79. This info will be added into the template of our oceanic clearance request.

F. We have 211 souls on board. That’s everyone: passengers, crew, and all the whiny kids riding in laps. The number below is the “assumed temperature” engine de-rate value used for takeoff (another topic for later). I’ll enter this into a datalink template later on; maintenance uses it to track engine performance.

G. This is the title of our assigned departure procedure (a series of initial routings, speeds and altitudes). We are cleared to depart via the “BELKO 6A.” I write it down because European departure controllers, on check-in after takeoff, often ask you to verbally verify which procedure you’re flying. Although you’ve got it loaded and have verified all the fixes and restrictions, the names can be confusing and easy to forget.

H. “T/A 50” means a transition altitude of 5,000 feet. This is the point at which our altimeters must be set to the standard pressure value of 29.92. This altitude varies country to country. “NADP” is a reminder that this airport requires us to fly a special noise-abatement departure procedure, with slightly different parameters for flap retraction and the setting of climb thrust.

I. Phonetic letter code (Foxtrot) for the most recent departure ATIS (Google it if you must), which I’ll pass along to ATC when necessary.

J. This empty section is where the arrival notes will go, later on. Items here might be the transition level for the destination airport, our gate number, and any anything else I might need to remember in a pinch. You might see radio frequencies here. For example, when flying into Los Angeles, controllers will often shift you from the north complex to the south complex, or vice-versa, on short notice, causing a flurry of arrival, approach, and taxi revisions. To stay a step ahead, I’ll write down all of the communications frequencies for tower, ground control and apron, in sequence, for both north and south sides. This info is on our charts, obviously, but it’s easier to have it on my cheat-sheet, ready to go, and not have to hunt around on my tablet while ATC is yelling at us.

Full disclosure: none of this is typical. Most pilots don’t bother writing much down aside from the flight number and maybe the departure fuel. But I’m a touch OCD, and, I don’t know, I’m just more comfortable this way. And it saves me from having to scroll through my iPad.

I suppose a regular pen would work just as well, but I like it all in red.

Related Story: