Q&A With the Pilot, Volume 6

AN OLD-TIMEY QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS SESSION.

Eons ago, in 2002, a column called Ask the Pilot, hosted by yours truly, started running in the online magazine Salon, in which I fielded reader-submitted questions about air travel. It’s a good idea, I think, to touch back now and then on the format that got this venerable enterprise started. It’s Ask the Pilot classic, if you will.

Q: I appreciated your rant about excessive public address announcements at airports and during flight. However, announcements from the cockpit can’t escape attention. Seriously, can some of your fellow pilots please stay quiet? We get what we need from the cabin crew; we don’t need the pilots piling on.

I’m okay with pilot PAs so long as they are professional-sounding, informational, jargon-free and brief.

I make one prior to departure. I say our names, then I give the flight time (I always round the minutes to zero or five), the approximate arrival time, and maybe a short description of the arrival weather. The whole thing takes fifteen seconds.

The names part is just to remind people that actual human beings are driving their plane. There’s such a disconnect between the cabin and cockpit; most passengers never even lay eyes on the individuals taking them across the country or across the ocean.

I do not start in with, “It’s a great day for flyin,’ and we’ve got eight of our best flight attendants back there for your safety and comfort,” blah blah blah. That style of folky-hokey chatter is embarrassing.

Q: When I fly, I always love the ka-thunk sound of landing gear coming down, as it signals we’re almost to our destination. Sometimes I notice it comes down much closer to touchdown than other times. Why?

Planes normally drop their landing gear at around 2,000 feet above the ground, or when passing what we call the “final approach fix.” That’s maybe three minutes from touchdown, give or take. But it varies, depending on airspeed, spacing with other traffic, and so on. Lowering the gear has a significant aerodynamic impact, mainly in the adding of wind resistance (that is, drag). Sometimes we drop it early to help slow down.

I remember going into JFK early one morning. The controllers initially kept us high and fast, then suddenly gave us a “slam dunk” clearance straight to the runway. We put the gear out at like 5,000 feet to slow down and increase our descent to the maximum possible rate. No pilot likes doing this, as it’s noisy and maybe a little disconcerting for passengers. But under the circumstances, it worked great.

At most carriers the policy is to have the gear down and the plane fully configured for landing no later than a thousand feet above the ground. The idea is to minimize power and pitch adjustments and maintain what pilots call a “stabilized approach.”

Q: And please cure this stupid irrational fear once and for all: could pilots ever forget to deploy the landing gear? What are the safeguards to ensure this doesn’t happen?

Verifying that the gear is down and locked is one of the checklist items prior to landing. There are also configuration warnings that will sound if the plane passes a certain altitude without the gear (or wing flaps) in the correct position.

On top of all that, if you still somehow managed to forget, the whole picture would look and feel wrong. The plane’s attitude would be off, the power settings would be strange, the sounds would be different.

Pilots of small private planes are known to land with their gear up from time to time, but I can’t imagine this happening in a commercial jet.

Q: I recently flew on a 737-900, in row 13. I was surprised to find that there was no window in this row, although there was ample space for one. Why?

You see this on a lot of planes. Usually it’s because there’s some sort of internal component — ducting, framing, or some other structural assembly — that doesn’t allow space for a window. Some turboprops are missing a window directly adjacent to the propeller blades, and you’ll find a strip of reinforced plating there instead. This is to prevent damage if, during icing conditions, the blades shed chunks of ice.

Q: I often listen in to air traffic control on the internet. On the approach control frequencies, pilots will call in and identify themselves “with” a character from the phonetic alphabet. For example, “Approach this is United 515 at ten thousand with Alpha or “Approach United 827, five thousand feet with Uniform.” What does this mean?

Every airport puts out a broadcast that gives the current weather, approaches and runways in use, and assorted other info particular to the airport at that moment (some of it, to be honest, unnecessary). This broadcast, called ATIS (automatic terminal information service), is identified phonetically between A and Z.

On initial contact with approach control (or with ground or clearance control when departing), pilots are asked to report in with the most current letter, verifying they’ve listened to the broadcast and have an idea of what’s going on. Each time something is updated, the broadcast advances to the next letter. I will call in “with Sierra,” and the annoyed controller will snap back, “Information Tango is now up.”

I use the words “broadcast,” and “listened to,” because traditionally crews would tune to a radio frequency for ATIS, and transcribe its highlights onto a slip of paper. Nowadays, at most larger airports, it’s delivered through a cockpit datalink printout or is pulled up on our iPads.

For no useful reason, much of the typical ATIS report is abbreviated and coded using all kinds of nonstandard shorthand, and takes some deciphering. Aviation is frustratingly averse to the use of actual words, preferring instead a soup of acronyms and gibberish. I mean, it’s not the 1950s anymore and we aren’t using teletype machines to communicate.

Q: Tell us something weird?

What’s weird is that I haven’t been to a rock concert in thirteen years.

That’s super weird, really, considering how deeply into music I once was, and how many hundreds of concerts I attended. I can’t explain why, exactly, but I developed a later-in-life disdain for live performances. They suddenly felt goofy and weird to me: Am I watching or listening? Where do I stand? And none of the songs sound right.

You’ll tell me I’m just getting old Whatever the reason, I stopped going, even when the musicians are ones I love.

My last time at a show was in 2010, when I went to see Grant Hart in Cambridge. Prior to that we go all the way back to 2004, when I saw the Mountain Goats, also in Cambridge. Both times I was on the guest list, which made the idea of a night out more appealing. I’m not sure I would’ve gone otherwise. (Somewhere in there was Curtis Eller the banjo guy, and some symphonies, but those don’t count.)

That said, I’m told by a reader that the Bob Mould show in New Hampshire a couple of weeks ago was great, and at least half of the songs he played were classics from the Hüsker Dü canon. I wanna say that I wished I’d gone (the last time I watched Mould play live was in 1995). I was in Tanzania on vacation, so my excuse is solid, but even if I’d been home I may not have done it.

Concerts are one thing, but worst of the worst is any kind of live music in a bar or restaurant. There’s almost nothing I hate more. At least at a concert you’re there because, presumably, you enjoy the music of the artist you’re seeing. The music in a bar may or may not be anything you like. It’s intrusive, and conversation becomes difficult.

Here I’ll make this airline-related: On layovers in Accra, Ghana, I used to love hanging out at the poolside bar at the Novotel. It was such a chill place, with the most relaxing vibe. Then they brought in a piano player. Now the racket made talking almost impossible. He’d sing, too, and the beer mugs would crack when he hit the high notes. I had to find a new place.

EMAIL YOUR QUESTIONS TO patricksmith@askthepilot.com

Related Stories:

Q&A WITH THE PILOT, Volume 1

Q&A WITH THE PILOT, Volume 2

Q&A WITH THE PILOT, Volume 3

Q&A WITH THE PILOT, Volume 4

Q&A WITH THE PILOT, Volume 5

Q&A WITH THE PILOT, Volume 6

Q&A WITH THE PILOT, COVID EDITION

Portions of this post appeared previously in the magazine Salon.

PHOTOS BY THE AUTHOR

The Death of Grant Hart, Five Years Later

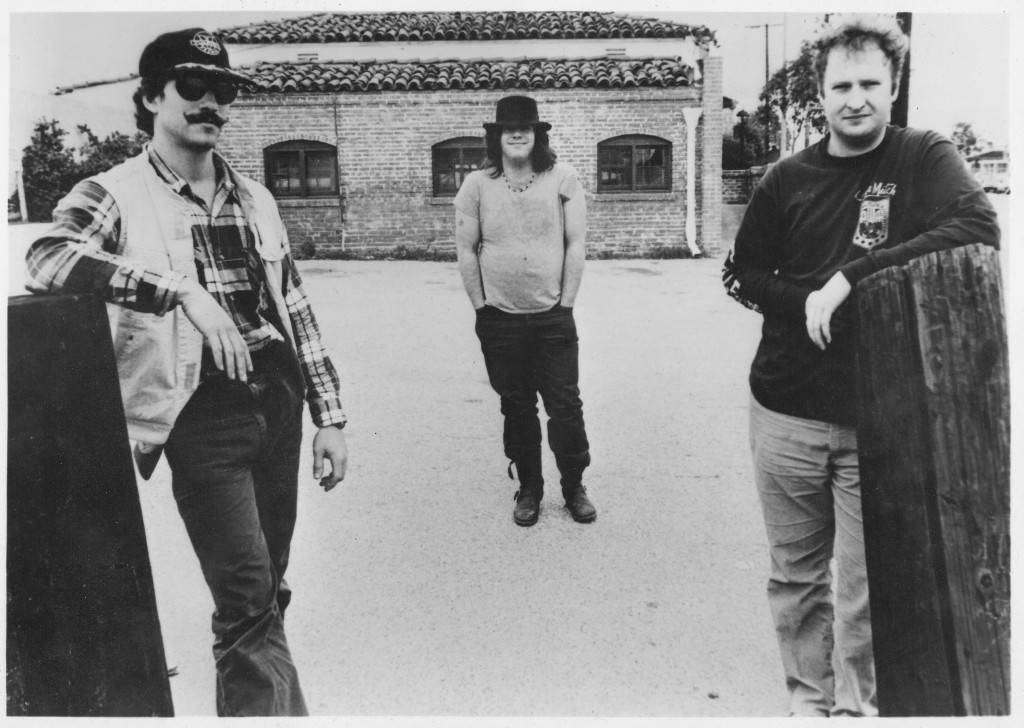

Greg Norton, Grant Hart, and Bob Mould in 1984.

September 14, 2022

TODAY MARKS the fifth anniversary of the death of Grant Hart, drummer and co-vocalist of the Minneapolis trio Hüsker Dü. He passed away on September 14th, 2017, from liver cancer. He was 56.

I’ve been known, in my obsessive, not-at-all objective fan-boy opinion, to describe Grant as the greatest songwriter of the 1980s. While such statements are presumed to contain a measure of hyperbole, how much so is the question. The pantheon of 1980s songwriters is a formidable one. There’s Pat Fish and Billy Bragg. There’s the long-forgotten Roddy Frame. And Strummer and Jones, of course (most of whose brilliance had petered away by 1982 or so). Thinking as unbiasedly as I’m able to, I suppose I’d put Grant in third place, just behind Pat Fish (a.k.a the Jazz Butcher, another of my heroes who died recently) and Bragg.

Grant’s old band-mate, Bob Mould, is somewhere on that list as well. Although Mould ended up more famous, and continues making music to this day, it’s hard to argue that Grant wasn’t the more talented songwriter, if not the more prolific one. Perhaps ironically, among Grant’s finest moments are his backing vocals at the end of one of Mould’s best songs, “Divide and Conquer,” from the Flip Your Wig album in 1985. He almost steals it away.

Grant Hart’s greatest hits…

“Terms of Psychic Warfare”

“Pink Turns to Blue”

“It’s Not Funny Anymore”

“Books About UFOs”

“Keep Hanging On”

“Diane”

“The Girl Who Lives on Heaven Hill”

“Standing by the Sea”

“Turn on the News”

“She’s a Woman (And Now He is a Man)”

Subject to change, depending on my mood. If you’re unfamiliar and curious, you can do the YouTube thing and have a listen.

That final one on the list, I’ve always felt, rests as Grant’s most under-appreciated song. It’s also the last song I ever saw Hüsker Dü perform live, at a club called Toad’s, in New Haven, Connecticut, in 1987. He later sang a delicate acoustic version (a recording of which is one of my most treasured possessions), the last time I saw him play, in Boston around twelve years ago.

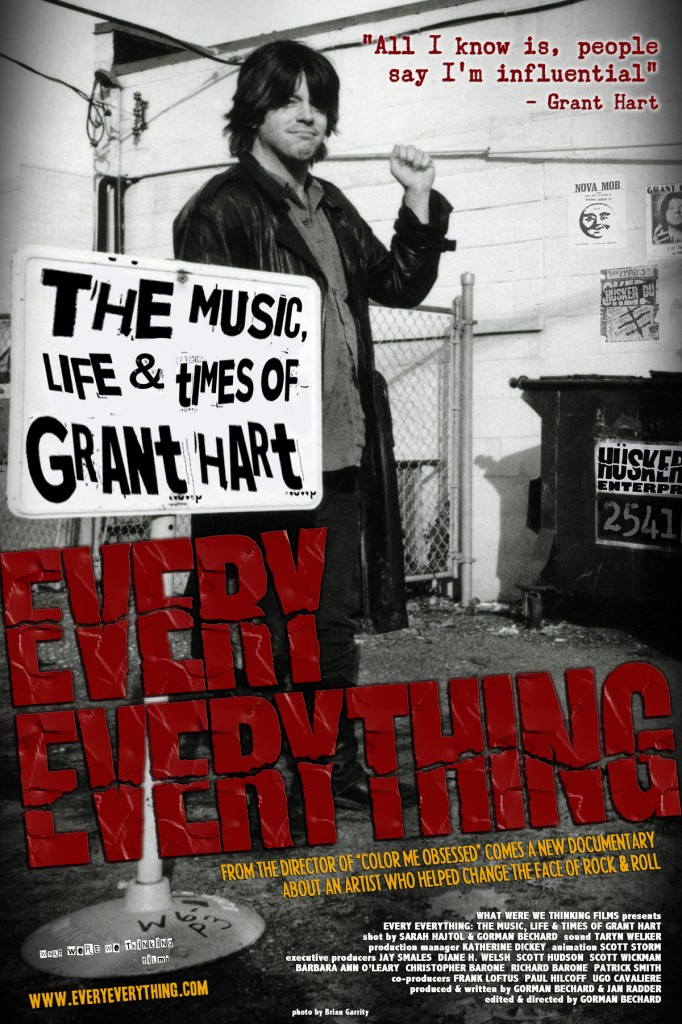

I was fortunate to meet Grant on several occasions, the first time in 1983, and I corresponded with him occasionally over the last couple of years of his life. Always gregarious, kind and accommodating, he even lent quotes to a few of my posts. I was a co-executive producer of “Every Everything,” the Gorman Bechard documentary about Grant’s life and work.

I could go on. I’ll finish with a small memory from a night in 1984. I was with some friends at a nightclub called The Living Room, in Providence, Rhode Island, standing in the parking lot just outside. Grant was there, feeding pieces of cheese to a stray dog. He’d hold out the pieces, one by one, raising his arm a little bit each time. And the dog would keep jumping, higher and higher, as everyone watched and laughed.

Related Stories:

THE GREATEST ALBUM OF ALL TIME

THE (SECOND) GREATEST ALBUM OF ALL TIME

Hüsker Dü photo by Daniel Corrigan.

Grant Hart thumbnail photo by Naomi Petersen.

Happy Birthday to the (Second) Greatest Album of All Time

IT WAS DECEMBER 30th, 1984, and Hüsker Dü were in from Minnesota again. They’d just wrapped up a show at a small auditorium in Concord, Massachusetts, and a small group of us were backstage talking to guitarist Bob Mould and drummer Grant Hart — the band’s co-vocalists and songwriters. A brand new album was due to hit the stores in only a week or two, and we all wanted to know: what was it going to sound like?

Zen Arcade had come out that past summer, and the indie rock world was still trying to absorb it. “Experimental” isn’t quite the right word, but Zen had played fast and loose with the boundaries of what punk rock, for lack of a better term, was supposed to sound like, bringing in acoustic guitar, piano, and a range of psychedelic effects. The upcoming project, it stood to reason, would take things ever further, would it not? Somebody — maybe it was me — brought this up.

“No way!” laughed Hart.

“Not at all,” added Mould. “This album is more like Land Speed Record than Zen Arcade!”

Land Speed, from way back in 1981, was a thrashy collection of quasi-hardcore songs played at nearly supersonic speed. Mould was being tongue-in-cheek — the album wouldn’t sound anything like Land Speed — but just the same he was dropping a hint: this wouldn’t be a record for the squeamish.

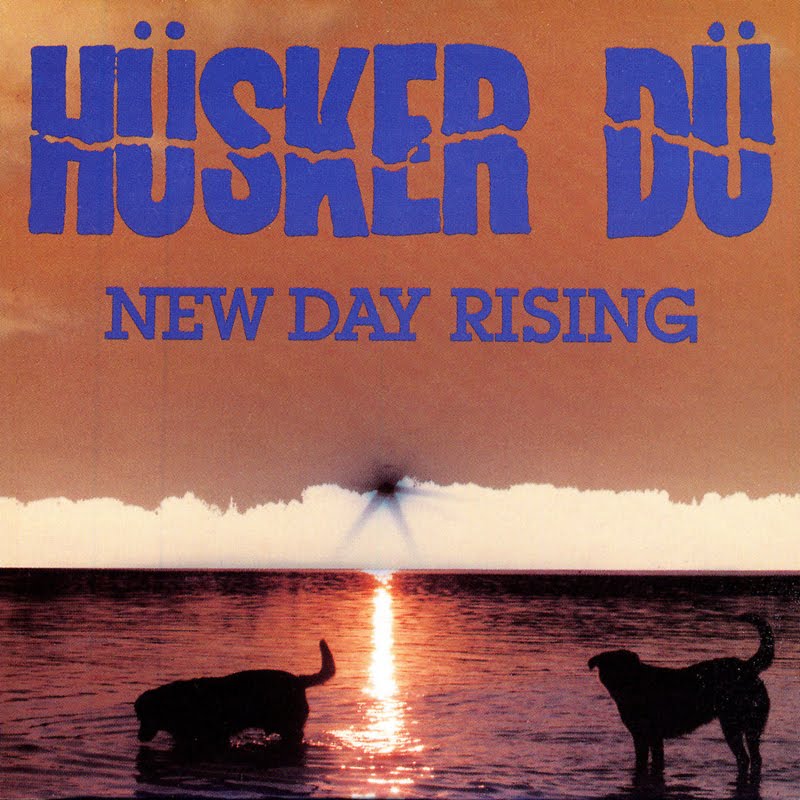

It was called New Day Rising — a remarkable fifteen-song LP that would wake the country from its winter freeze in January of ’85. There is nothing subtle or subdued about this album. There are no touchy-feely instrumentals, no acoustic time-outs — enjoyable as those things were on Zen. Sure, the melodies and catchy choruses are there beneath it all, in typical Hüsker fashion, but New Day Rising is power from start to finish; forty fearless minutes of ferocious exuberance.

I’m not going to argue that Zen Arcade isn’t the better or more important album. It’s all the things the pundits have called it from the start: monumental, groundbreaking, a reevaluation of everything we thought punk rock could or should be. It’s a masterpiece. But almost too much of one, moody and broody at times, and a little too — what’s the way to put it? — serious. New Day is the brasher and looser album, with Mould and Hart clearing out the pipes, with nothing left to prove and absolutely hitting their strides. It is, if nothing else, the most supremely confident-sounding album of all time.

And it’s made all the more so through a daring, some might say controversial sound mix. There’s a very particular sound to this album — a treble-heavy mix that is like nothing before or since, in which every song is enveloped in a fuzzy, fizzing, needles-pegged curtain of sound. Many people — including the band members themselves, reportedly — have always rued this peculiar mix, but to me it’s the ideal vehicle for the group’s sound. Here is the “Hüsker buzz,” as I call it, naked and cranked to eleven. (What I wouldn’t give to hear some of the cuts from Zen Arcade or Flip Your Wig** remixed like this.) The style is “hot” in soundboard lingo, but to me it has a crystalline, sub-zero quality: it sounds like ice. The songs are as melodically solid as any top-40 hits of the time, but all whipped up in a great Minnesota blizzard.

Greg Norton, Grant Hart, and Bob Mould, in 1984.

Photo by Naomi Petersen.

First time listeners will know exactly what I mean within the first ten seconds of the title cut. “New Day Rising,” the song, begins with a lead-in of anxious drumming — Hart pounding away, as if to say “Let’s this this fucking thing started!” — and then comes the crescendo, a guitar-blast crashing over you in a huge squalling wave: equally furious and melodic; chaotic yet strangely orchestral. It’s a breathtaking opening and the perfect pace-setter for the rest of the record. (Robert “Addicted to Love” Palmer once found it a compelling enough song to cover.)Next up Hart’s “Girl Who Lives on Heaven Hill.” There’s something sour and vaguely out of tune about this song that for years I could never get past. Until one day it hit me: it’s supposed to be like that. Hart takes the all the nicety and sing-songy pleasures of “It’s Not Funny Anymore” or “Pink Turns to Blue” — songs that are almost too easy to like — and twists and bends and sets fire to it. Then, between the second and third stanzas, Mould comes in with a guitar solo that tears the rest of it — along with your eardrums — to pieces. It’s a haunting, mesmerizing, and a little bit frightening three minutes.

The third cut is Mould’s “I Apologize.” This is arguably the best song he ever wrote, perhaps outclassed only by the “Eight Miles High” cover, or by “Chartered Trips” from side one of Zen Arcade. Here is the song Green Day and its ilk only wish they could have made: poppy and powerful, but without the slightest hint of heavy metal pretension. And is it just me, or you can you almost hear Michael Stipe singing this one? The chorus is uncannily infectious in the style of old REM songs of the same era. It’s as if you took a song like “South Central Rain” and split every atom of it: all that sweet Georgia lilac exploded into a sort of nuclear ice storm. (Putting Hüsker Dü and REM in the same sentence might seem incongruous, but it’s not by accident that they once toured together.) Listen to “I Apologize” here. Don’t skip the final fifteen seconds, and play it loud.

Further along is one of the great sleepers in the Hüsker Dü canon: Mould’s “Perfect Example.” This is the record’s only true “slow” moment — the band’s idea of a tearjerker. It closes out side one, sung by Mould in a kind of passive-aggressive whisper, with Hart (barefoot no doubt, as he always played) double-thumping the bass drum in perfect synchronicity to a human heartbeat. The song clashes to a close on the word “perfect.” Had the album ended right there, already it’d be a classic. Except that’s only the first side.

Although only two of the cuts are his, Grant Hart effectively owns side two. This is by virtue of “Terms of Psychic Warfare” and “Books About UFOs,” both of which are unforgettable. Listen to “Terms of Psychic Warfare” here, with its signature bass riff and beautifully cascading vocals.

The better one, though, is “Books About UFO.” Equal parts deafening, frenetic, melodic and catchy, the track is backed with piano. From any other band, in any other context, this effect would probably sound gimmicky. Not so here. Indeed, it’s almost as if this song were written for piano from the start. “For all the speed and clamor of their music,” the music journalist Michael Azerrad once wrote, “Hüsker Dü was perhaps the first post-hardcore band of its generation to write songs that could withstand the classic acid test of being played on acoustic guitar.” That’s an excellent point, but the heck with that, I want to hear Grant playing an all piano version of “Books About UFOs.”

“I’d also recorded a slide guitar on ‘Girl Who lives on Heaven Hill,'” Grant Hart remembers. “But when I showed up after that session, Spot [the album’s co-engineer] and Bob issued an ultimatum: either the piano goes from ‘UFOs’ or the guitar goes from ‘Heaven Hill.’ After stating my case, which was ‘what does one have to do with the other?’ I relented and said if one had to go, let it be the slide guitar.

Probably the right decision. “UFOs” is one of the most furiously pretty, and downright interesting songs you’ll ever hear.

Norton, Hart, and Mould.

Photo by Daniel Corrigan.

To the end, Hart, who passed away in 2016, held some strong resentment against the way Spot, who’d been sent to Minneapolis from Los Angeles by SST Records to oversee the project, handled his duties. Spot shared the engineering tasks with the band members and their longtime collaborator Steve Fjelstad, but as Hart once explained it, “SST decided that we were not to be the masters of our own destiny, and sent Spot to babysit/spy/sabotage our record. He did not give Steve Fjelstad the respect he deserved, treating him as an assistant.””Another thing I remember,” said Hart, “was not being allowed to make my own choices as far as re-doing vocals that I thought I could better. On ‘Heaven Hill’ you could hear the sound of some lumber, that had in been in the booth during remodeling, falling to the floor!”

Well, all of that aside, it’s tough to have too much issue with the finished product.

The album comes to an end with the charging, spiraling, sonic immolation of Bob Mould’s “Plans I Make.” Fasten your seatbelts for this one. It’s not the jammy, psychedelic marathon of “Reoccurring Dreams,” the 14-minute instrumental that closes Zen Arcade, but it’s a wringer, an earsplitter that, when it finally crunches to its conclusion, leaves the listener with no choice but to sit spellbound for a time.

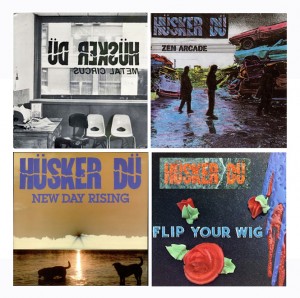

If it seems like only yesterday that I was writing about the 30th anniversary of Zen Arcade, which had been released in June of 1984. It’s fascinating testament to Hüsker Dü’s talent and tireless work ethic that two such brilliant albums could have been released within a mere seven months of each other. And these were bookended, I should add, by two other highly impressive records — Metal Circus and Flip Your Wig, from October of ’83 and September of ’85 respectively. A spectacular four-record punch in a span of under two years.

And if forced to choose, I’d say New Day Rising sits the pinnacle of that run. This is Hüsker Dü at the very apex of its career, and one of the finest moments in the whole history of what used to be called underground rock.

Meanwhile, unless I’ve missed something, none of the big music magazines or websites gave New Day so much as a mention on its 20th, 15th, or 30th birthdays. For that matter, do younger music fans have any sense of what the 1980s truly were like? This was the richest and most innovative period in the whole history of independent music, but rarely is it acknowledged as such. As popular culture has it, serious rock music skipped the 80s entirely. When pundits do take the decade seriously, we tend to see the same names over and over. It’s both frustrating and unjustified that Hüsker Dü never developed the same posthumous cachet that others of their era did. Like the Replacements, for example, or Sonic Youth. Hüsker Dü could run circles around either of those two, but never became “cool” in quite the same way.

I suppose it’s due to a total absence of what you might call sex appeal? To say that Hüsker Dü never cultivated any sort of image, in the usual manner of rock bands, is putting it mildly. For one, they never looked the part. These were big, sweaty, chain-smoking guys who, it often seemed, hadn’t shaved or showered in a while. Norton, trimmest and most dapper of the threesome, wore a handlebar mustache many years before such things were trendy among hipsters. It wasn’t cool; it was odd. And not until their eighth and final album that the band include a photo of itself on an album cover (the scratched-out images on Zen Arcade notwithstanding).

This modesty, for lack of a better description, was for some of us a part of what made Hüsker Dü so special. But it has hurt them, I think, in the long run.

The idea that the Replacements (much as I loved their debut album, which I consider the best garage-rock record of all time, and which includes a shout-out called “Somethin’to Dü”) were in any way a better or more influential band than Hüsker Dü is too absurd to entertain. Meanwhile the beatification of Sonic Youth, maybe the most overrated outfit of the last forty years, goes on and on. Not long ago Kim Gordon got a profile in the New Yorker. I’m still waiting for one of the writers there to devote a story to Bob Mould.

Or better yet, to Grant Hart. Twenty-five years, more or less, that’s how long it took me, to realize that it was Grant, not Bob, who was the more indispensable songwriter and who leaves the richer legacy. In the old days it was trendy to claim that Grant was the real genius behind Hüsker Dü. You’d be at a party and some asshole would say, “Those guys would be nothing without that drummer.” I’d always scoff that off. The mechanics of the band, for one, made it difficult to accept: Grant was the drummer, after all, and drummers are never the stars. And there was Bob, right at the front of the stage with that iconic Flying-V. But those assholes were on to something.

That shouldn’t be an insult to Mould. Not any more than saying Lennon was a better songwriter than McCartney. Both were brilliant. But when I flip through the Hüsker canon, I can’t help giving Hart the edge. There’s a soulfulness to his songs sets them apart. They’re not necessarily “better” so much as they resonate in a different and deeper way. On New Day Rising, Mould gave us “I Apologize” and “Celebrated Summer.” But Hart gave us “Terms of Psychic Warfare” and “Books About UFOs.” On earlier records it was “It’s Not Funny Anymore,” “Diane,” “Pink Turns to Blue,” the list goes on. Hart’s “She’s a Woman (And Now He is a Man”) from the often intolerable Warehouse album is, to me, a classic sleeper and the most under-appreciated Hüsker song of them all.

His solo work, too, was at least as robust as that of Mould. Songs like “The Main” and “The Last Days of Pompeii” are as good or better than anything Mould has given us post-Hüsker. But while Mould went on to some notoriety and commercial success, Hart labored in comparative obscurity. This was always irritating and unfair.

But Grant, maybe, was all right with this. “I have always based my movements on those of fugitives or criminals,” he once said to me. “The less attention you attract, the freer you remain! I wish to be an artist, not a celebrity.”

Related Story:

Now and Zen. The Greatest Album of All Time Turns 30

Zen Arcade at 40

HüSKER Dü WERE A TRIO from Minneapolis. Guitarist Bob Mould and drummer Grant Hart sang and wrote the songs. Greg Norton played bass guitar and chipped in on vocals.

A punk band, you would have to call them, as throughout the early and mid-1980s they toured and recorded primarily within that realm. At heart, though, they were always something else. “Hüsker Dü seemingly defined the punk ethos,” wrote Terry Katzmann, one of the band’s longtime friends once put it, “without necessarily embracing or endorsing it.” Perfectly put.

The band could play louder and faster than anyone alive. When this got constraining, they’d bring in 60s-style pop hooks, psychedelia, heavy metal. Often at once, which to me is the kernel of what made them great. They were never powerful or something else. They were both, everything, all at the same time.

This blending of styles alienated many of the more orthodox fans within the punk scene. It also won the acclaim of many more, and it’s by no means a stretch to consider Hüsker Dü one of the most influential acts ever to emerge from the American underground.

Before its stormy demise in late 1987, the band would release six full-length albums, two EPs, and a catalog of singles and extras. But the pinnacle of all that output was Zen Arcade, first delivered to stores in July, 1984, by California-based SST records.

I remember the day I bought it. Newbury Comics — the one on Newbury Street — on a midweek afternoon, sunny and hot. I was eighteen years-old.

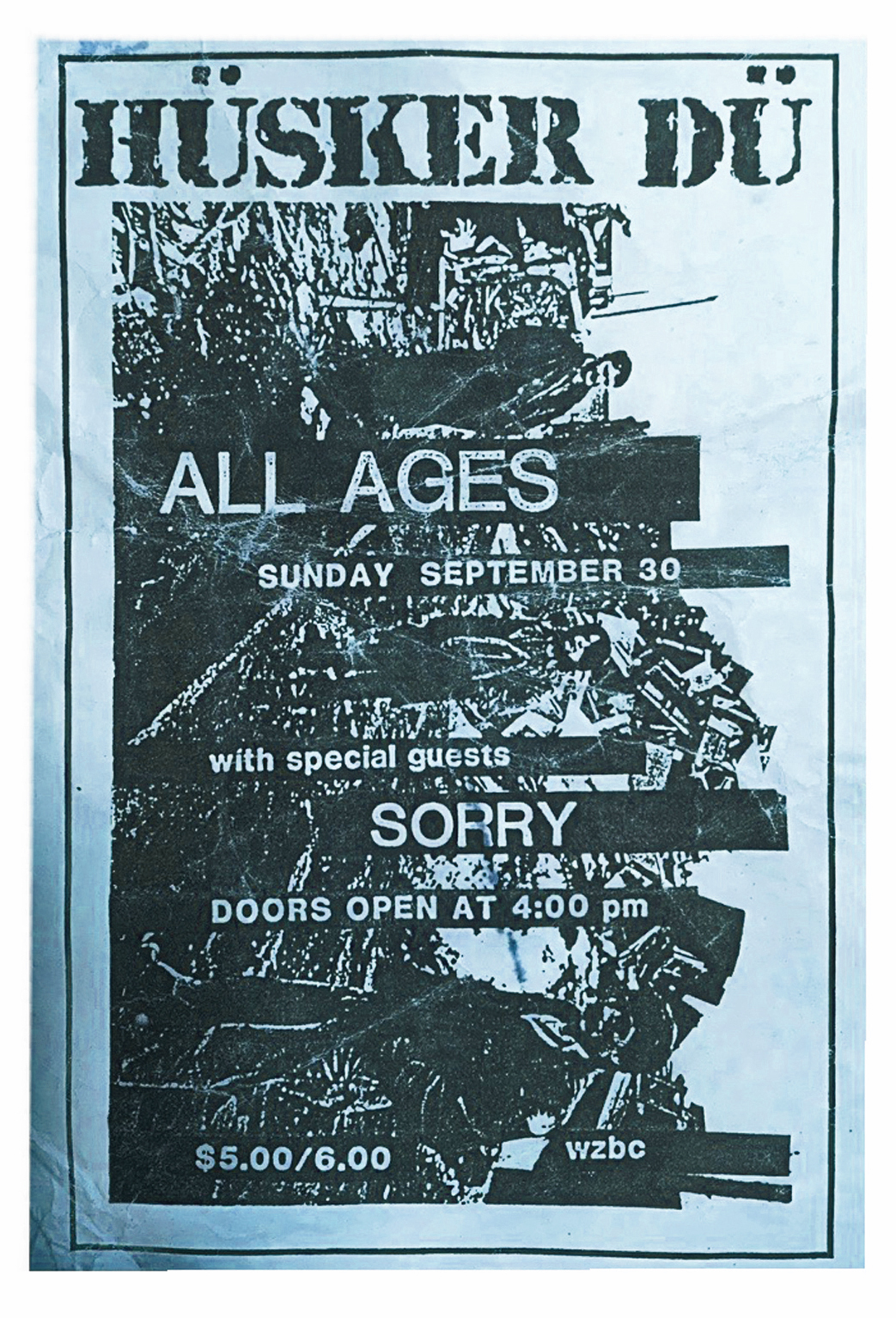

We knew there was an album coming coming out, but weren’t sure when, exactly, it would hit the racks. In these pre-Internet times, news of such things was always unclear and came sporadically, delivered by college radio or gleaned through your network of friends. Sometimes it was a paper flyer glued to a mailbox or tacked to a record shop bulletin board. Nobody was a bigger Hüsker Dü fan than I was, but this latest album, due in the stores at any moment — I didn’t even know the title.

Suddenly there it was, on a rack up front. It was called Zen Arcade, whatever the heck that meant. I picked it up and, hey, what’s this, it’s a double album! As a teenage punk rocker weaned on Black Flag and Minor Threat, with a rather one-dimensional appreciation for music, the very weight of the thing, together with the heady title and the washed-over, almost Impressionist cover art was intimidating. It seemed so arty and grown-up. It also made me curious. What was this strange record?

What it was, and what it remains almost forty years later, is the greatest indie-rock album of all time — if not, in my extraordinarily biased opinion, the greatest rock album, period.

“The most important and relevant double album to be released since the Beatles’ White Album,” bragged SST’s own press release. There was some confidence for you, to say the least, when you consider the world of underground music in 1984. This was not only an obscure band, but an entire musical domain that existed far below the mainstream waterline. Then as now, the idea of comparing a little-known indie band to the Beatles seemed at best pretentious and at worst totally absurd.

Was it?

Twenty-three songs is a lot of music, but this is one the rare two-record sets that isn’t bogged down by its own overreaching or conceit. The scourge of most double LPs, back when there was such a thing, is they went on for too long — padded with live cuts, covers, and extras (heck even London Calling has its throw-aways). There’s no filler in Zen Arcade. Each and every song, from the shortest (44 seconds) to the longest (14 minutes), belongs exactly in its place.

Yes, that includes “The Tooth Fairy and the Princess.” The longest-named song on the record is probably the most easily dismissed. But it’s a clever little tempest of a song, littered with switchbacks and melodic explosions.

The album is best savored not as a CD — and for heaven’s sake not as a download — but in the old, cardboard-and-vinyl package. That’s a quintessentially record-snobbish thing to say, but unavoidable in this case, where each of the four sides is a distinct chapter with its own temperature and architecture.

Greg Norton, Grant Hart, and Bob Mould, circa 1984.

Photo by Naomi Petersen.

Side one gets going without the slightest fuss, with the snap and kick of Bob Mould’s “Something I Learned Today,” eventually winding down with “Hare Krsna,” a booming, tambourine-backed instrumental (mostly).

The first time I heard “Hare Krsna,” sizzling over the stereo in a Boston area record shop not long after the album’s release, I remember the young clerk furrowing his brow, looking up toward the speakers and saying, “Somebody needs to write a dissertation about this song.” I couldn’t care less if they were plagiarizing a Bo Diddley riff; “Hare Krsna” is a mesmerizing, three-and-a-half minute cyclone of melodic chaos that still gives me the chills. Listen to Mould hitting the strings at time 0:44.

Side one alone is unforgettable. And there are three more to go. This is the ultimate workhorse album from the ultimate workhorse band, one so rich with sonic nooks and crannies that an in-depth listen leaves you not only battling tinnitus, but tired. So many changes from fast to slow, hard to soft, love to hate, all in perfect working sequence. And each side-break is a perfectly placed respite. I can’t think of a more brilliantly arranged opus than Zen Arcade. “The closest hardcore punk will ever get to an opera,” wrote David Fricke of Rolling Stone.

Indeed, this is a proverbial concept album — a musical story, in the spirit of the Who’s Tommy, allegedly describing the journey and tribulations of a young man. He leaves home, maybe joins a cult, maybe joins the Army…whatever. Alt-rock historians love reminding us about this, but you’re free to ignore it. Any lyrical backstory is incidental to the record’s impressiveness.

You’ll find a gamut of effects: acoustic guitar, chairs being thrown, waves breaking, whispers and chants. There’s even the breezy piano of “Monday Will Never be the Same.” (If Ken Burns ever directs a documentary about the history of alt-rock, the tinkling of “Monday” needs to be its backing theme.) Such eclectics are brave, maybe, for what was supposedly a punk album, but they never become maudlin or melodramatic. If you think today’s co-opted rockers are clever with the tempo card, shifting from tough to tender, check out Grant Hart’s “Never Talking to You Again,” a sing-along from side one done entirely in 12-string acoustic. “Heartfelt” is the word that jumps to mind, but it’s not the syrupy strum you’d hear nowadays. The song is biting and sharp — an attack. Ditto for “Standing By the Sea,” with Hart’s cathartic bellows set against bassist Greg Norton’s eerie thrum and the soothe of a crashing surf.

Back in ’84, the rock critic Robert Christgau chose Hart’s “Turn On the News,” from side four, as his “song of the year.” Christgau said many flattering things about Hüsker Dü, but that one was the gimmie pick, like saying the Concorde is your favorite airplane. It’s an easy song to like, but an even easier one to outgrow. If the album has a best song, it’s probably Bob Mould’s neo-pscychedelic “Chartered Trips,” the fourth cut off side one. (“Trips” is almost Mould’s single greatest work, topped only by his spectacular rendition of the Byrds’ “Eight Miles High,” released as a single just prior to Zen Arcade.)

Runner-up would be Hart’s “Pink Turns to Blue,” from side three. Officially the credits for this one list both Mould and Hart, but really this is Grant’s piece. He took all the hook and melody of his earlier masterpiece, “It’s Not Funny Anymore,” and sandblasted it into a haunting anthem of love, drugs, and death. The song is simply gorgeous — and a little bit terrifying. Score it ahead of “Chartered Trips” if you want. I’m not going to argue.

September, 1984, in the dressing room at the Channel.

Boston Rock magazine.

“Pink Turns to Blue” follows “One Step at a Time,” a brief piano time-out that, as much as anything else, allows the listener to catch his or her breath. The pregnant pause between the last note of “One Step” and the opening chord of “Pink” is like those one or two seconds between a lightning bolt and a thunderclap, and is one of the record’s strongest moments. It reminds me of the similarly unforgettable transition into “Sweet Jane” on the Velvet Underground’s Loaded album.

Before going further, I’m aware how this favorite songs thing can turn tedious pretty quickly. Grant Hart himself once offered a disclaimer: “People will always embrace different songs for different reasons,” he told me. “A song that might seem terrible filler, serving only to move the story along, will be someone’s favorite on the album. Bob and I were both responsible for those kind of songs.” Of my beloved “Hare Krsna” Grant claims that he was merely “furthering the story without adding much musically.” Hart felt similarly about some of Mould’s thrashier and more “hardcore” material.

To his point, not all of the album is easy to like and, depending on your ear and level of patience, the value of certain songs might not reveal itself for some time. For me it was twenty years before the first four songs from side two (Mould at his most furious) finally clicked. They’d always been so noisy and formless. Suddenly they weren’t. This was partly a context thing, maybe: the album, like wine, getting better not despite its age, but because of it. It took the overall shittiness of music in the 21st century to underscore the greatness of cuts like “Pride” and “The Biggest Lie” — mere footnotes in 1984. They’re awesome songs, at once explosive and subtle, but buried amidst so many other and perhaps better choices, that even the band’s most devoted fans tend to skip them over.

Similarly it was decades before I learned to appreciate “Broken Home, Broken Heart,” the second song on the album, for the gem that it is, tucked anonymously between “Something I Learned Today” and Hart’s “Never Talking to You Again,” with Norton’s bass stealing the show. And that a supposed punk rock album could jump from the fury of “Broken Home” to the acoustic beauty of “Never Talking”, without so much as a flinch, was a watershed in American music.

Though not entirely a surprise. Even at breakneck velocity there always was something ineffably refined and just, well, different about Hüsker Dü. If pressed to explain, one might break out 1982’s Everything Falls Apart EP. Amidst side one’s hypsersonic avalanche is Hart’s cover of Donovan’s 1966 hit, “Sunshine Superman.” Playful, perhaps, on the face of it, until you hear how un-ironic the remake is, without a note’s worth of smirk or parody. This wasn’t a joke.

Later, on his solo tours, Bob Mould would often play acoustic versions of some of the hardest and fastest Hüsker Dü songs — cuts like “In a Free Land” or “Celebrated Summer” — and the results were startlingly pretty. That’s just not going to work if you’re Black Flag, the Dead Kennedys or Bad Brains. Or Nirvana. Run even the noisiest Hüsker song through a centrifuge and something elegant reveals itself.

Concert flyer, Boston, 1984. Author’s Collection.

With its blend of hippie love and hard rock thunder, Zen Arcade would, in a way, finish the job that the Velvet Underground and even the Beatles had tinkered with earlier. But while the blending of power/pop extremes was nothing new, the Hüskers pulled it off in a way that was never gimmicky (not until their lazy cover of “Love is All Around,” the Mary Tyler Moore Show theme, in 1986), and, most remarkably, did so on such terrain –- the American hardcore punk scene –- where nobody expected it or even believed it possible.

“A strenuous refutation of hardcore orthodoxy,” as Michael Azerrad puts it in his book, Our Band Could Be Your Life: Scenes from the American Indie Underground, 1981-1991. “Zen Arcade was the final word on the [punk rock] genre, a scorching of musical earth. The album wasn’t only about Hüsker Dü coming of age — it was about an entire musical movement coming of age.”

Zen Arcade is the album Nirvana and its contemporaries only wish they could have made: intelligent, clamorous, and hashing out more torment and passion in four sides than all the grungers and headbangers since. All without a hint of heavy metal pretension: to think anyone could concoct a fourteen-minute bombast of guitar leads and layered distortion — “Reoccurring Dreams,” side four — and have it not come out self-indulgently.

All right, maybe it’s a little self-indulgent. But listen carefully enough and you’ll learn that “Dreams” can be parsed into six or seven subsections, each of them breaking through to the next, right in the nick of time. The song is long, but never wears out its welcome. It belongs there, in its entirety. An epic album deserves an epic close.

And when the 40-second whine at the end of “Dreams” is at last pinched off, the album burning to a close in a congealed, numbing squeal, the silence that follows is palpable, as dramatic as any of record’s loudest moments. Only then, as your senses regain their composure, is it apparent that your notions of punk rock are changed forever.

But not everybody, however — not even Grant Hart — has openly accepted such lavish praise. Hart once described Zen as the album that fans “tend to wear on their sleeves.” Did he mean people like me? Have I been too sentimentally fond of it for some reason?

“The impact of Zen Arcade on the Zeitgeist is hilarious to me,” said Grant. “Hilarious in the almost alchemical-mechanical way it has been embraced by true music fans and hipster-flipsters alike. When somebody states that Zen is their favorite LP, I get the notion to ask why. As we move further from the time it was released, it seems I get more honest answers.”

My honest answer is that I like it the best because it sounds the best, and by the sum of its parts it is the best. And for the record, Zen Arcade is not my “favorite” Husker Dü LP. New Day Rising is my “favorite” Husker Dü LP. But that’s getting personal. When you look at it objectively, Zen is the better and more profound of the two.

Hüsker Dü were nothing if not prolific. A mere six months after Zen Arcade came New Day Rising, which woke the country from its winter freeze in January, 1985. These are two best albums of the 1980s, and they appeared within six months of each other!

Eight month’s after that came “Flip Your Wig,” the band’s last album before signing with a major label. Flip suffers from terrible production but is nonetheless memorable, highlighted by Hart’s pièce de résistance, “Keep Hanging On.” Prior to Zen, meanwhile, was Metal Circus, a brilliant seven-song EP from 1983. Together, these four records represent, easily, the most potent 1-2-3-4 punch in the annals of indie music. All released in the astonishing space of less than two years. That’s simply incredible.

In 1986 and 1987, having moved from SST to Warner Brothers, Hüsker Dü released two disappointing and anticlimactic albums,”Candy Apple Gray” and “Warehouse: Songs and Stories.” I’m unsure which of these two records annoys me more, but neither, really, has much place in this conversation. “Candy Apple Grey” does well at the start and finish — I’ve always loved the gothic guitar squall of the opener, “Crystal,” as well as the closer, “All This I’ve Done For You” — but the rest is flyover country, including Bob Mould’s abominable “Too Far Down,” which has to be the ugliest song he ever recorded.

With Warehouse, it’s as if they took Zen Arcade placed it on a table in front of them and said, “Okay how can we ruin this?” Like Zen Arcade, it’s a double LP. Unlike Zen Arcade, it’s bloated with filler. I’ll always love “Back From Somewhere” and “She’s a Woman (and Now He Is a Man),” but the plodding, uninspired likes of “Ice Cold Ice,” “You’re a Soldier,” and too many others, anchor this one at the bottom of the Hüsker canon.

Bob and Grant had their power struggles, but as a songwriting tandem their talents were wonderfully complementary — think Strummer and Jones, or McCartney and Lennon. This was much of what made the band so great. By the time “Warehouse” warbles to a close, clearly this synchronicity is unraveling. Hart, at least, holds his own on this record, while Mould’s songs are overextended and lazy. Depressing as it was, you could say that Hüsker Dü broke up exactly when it needed to.

Meanwhile, unless I’ve missed something, none of the big music magazines or websites gave Zen Arcade so much as a mention on its 20th, 15th, or 30th birthdays. Some years ago Spin awarded it the number four spot on its ranking of the hundred best-ever “alternative” records, and Rolling Stone, in a manic best-of-the-80s list, once gave it lip service at number 33. But what since then? Instead we have bands like Green Day winning Grammys.

For that matter, do younger music fans have any sense of what the 1980s truly were like? This was the richest and most innovative period in the whole history of independent music, but rarely is it acknowledged as such. As popular culture has it, serious rock music skipped the 80s entirely. When pundits do take the decade seriously, we tend to see the same names over and over. It’s both frustrating and unjustified that Hüsker Dü never developed the same posthumous cachet that others of their era did. Like the Replacements, for example, or Sonic Youth. Hüsker Dü could run circles around either of those two, but never became “cool” in quite the same way.

I suppose it’s due to an absence of what you might call sex appeal. To say that Hüsker Dü never cultivated any sort of image, in the usual manner of rock bands, is putting it mildly. For one, they never looked the part. These were big, sweaty, chain-smoking guys who, it often seemed, hadn’t shaved or showered in a while. Norton, trimmest and most dapper of the threesome, wore a handlebar mustache many years before such things were trendy among hipsters. It wasn’t cool; it was odd. And not until their eighth and final album did the band included a photo of itself on an album cover (the scratched-out images on Zen Arcade notwithstanding). It was a small, back-cover pic that almost feels like an afterthought, or something the record company made them do.

This modesty, for lack of a better description, was for some of us a part of what made Hüsker Dü so special. But it has hurt them, I think, in the long run. (As has the fact that only the band’s final two albums are available on iTunes. But that’s another story.)

The idea that the Replacements (much as I loved their debut album, which I consider the best garage-rock record of all time, and which includes a shout-out called “Somethin’to Dü”) were in any way a better or more influential band than Hüsker Dü is too absurd to entertain. Meanwhile the beatification of Sonic Youth, maybe the most overrated outfit of the last forty years, goes on and on. Not long ago Kim Gordon got a profile in the New Yorker. I’m still waiting for one of the writers there to devote a story to Bob Mould.

Or better yet, to Grant Hart. Twenty-five years, more or less, that’s how long it took me, to realize that it was Grant, not Bob, who was the more indispensable songwriter and who leaves the richer legacy. In the old days it was trendy to claim that Grant was the real genius behind Hüsker Dü. You’d be at a party and some asshole would say, “Those guys would be nothing without that drummer.” I’d always scoff that off. The mechanics of the band, for one, made it difficult to accept: Grant was the drummer, after all, and drummers are never the stars. Meanwhile there was Bob, right at the front of the stage with that iconic Flying-V. But those assholes were on to something.

That shouldn’t be an insult to Mould. Not any more than saying John Lennon was a better songwriter than Paul McCartney. Both were brilliant. But when I flip through the Hüsker canon, I can’t help giving Hart the edge. On New Day Rising, for instance, Mould gave us “I Apologize” and “Celebrated Summer.” But Hart gave us “Terms of Psychic Warfare” and “Books About UFOs,” two of the most electrifying songs of the 80s. “It’s Not Funny Anymore,” “Diane,” “Pink Turns to Blue,” the list goes on. Hart’s “She’s a Woman (And Now He is a Man”) from the often intolerable Warehouse album is, to me, a classic sleeper and the most under-appreciated Hüsker song of them all.

His solo work, too, was at least as robust as that of Mould. Songs like “The Main” and “The Last Days of Pompeii” are as good or better than anything Mould has given us post-Hüsker. But while Mould went on to some notoriety and commercial success, Hart labored in comparative obscurity. This was always irritating and unfair.

But Grant, maybe, was all right with this. “I have always based my movements on those of fugitives or criminals,” he once said to me. “The less attention you attract, the freer you remain! I wish to be an artist, not a celebrity.”

Hüsker Dü in 1986. Photo by Daniel Corrigan.

Related Story:

HAPPY BIRTHDAY TO THE (SECOND) GREATEST ALBUM OF ALL TIME

Grant Hart died in September, 2017. A few years ago, filmmaker Gorman Bechard released a movie about him. “Every Everything” is 93 minutes of Grant — and only Grant — proving himself to be one of the more oddly captivating storytellers you’ll ever have the pleasure of listening to.

Bechard had previously interviewed Grant for “Color Me Obsessed,” his film about The Replacements, and was taken with him. “Grant is one of the most influential musicians ever,” said Bechard at the time. “Beyond that, he’s as smart and funny as anyone on the planet.”

You may not be familiar with Hart, but he was among the most important songwriters of our time, and “Every Everything” is a brave and absolutely necessary tribute to one of the unsung heroes of modern music. Click the picture for more info…

— The one song I would probably have pruned from Zen Arcade is “Dreams Reoccurring,” the noisy little instrumental from side one. You’ve got the fourteen-minute version later on; do we really need this miniature version too? And the fact that “Indecision Time” isn’t so great either… it creates kind of a dead spot on the first side. In its place I’d have put “Some Kind of Fun,” one of the outtakes.

— The greatest concert I ever attended was an impromptu Husker show at a place called Harvey Wheeler Hall, in Concord, Massachusetts, on December 30th, 1984. It was a last-minute gig arranged by David Savoy, a Concord native who also was the band’s manager at the time (and whose suicide a few years later was partly responsible for its breakup). There was no stage; the band set up on the floor of what, in my memory, was a simple classroom. There were fewer than a hundred people there, and we stood or sat cross-legged. The set ended when Grant cut his finger on a cracked drumstick during a cover of the Beatles’ “Ticket to Ride.” My best friend at the time, Mark McKay (who later became the drummer for the post-hardcore band Slapshot), gave him a band-aid. When it was over we went backstage, as it were, and chatted a while with the band.

— A few years ago, Paul Hilcoff, the curator of the painfully exhaustive Hüsker Dü fan site, mailed me a compact disc recording of that entire concert. I had no idea there was one. What a startling feeling it is to discover, many years on, that a recording exists of one of your most cherished memories. Except, the CD still sits on my bookshelf, as yet unlistened-to. One of these days I’ll summon up the courage to actually play it. Listening to that recording, provided I’ve got the emotional muster, will be the closest I ever get to time travel.

— I once played Frisbee with Bob Mould. June 21, 1984, it was, prior to a show in Easthampton Massachusetts. There were four of us playing: me, Bob, a local Boston fanzine writer named Al Quint, and the aforementioned McKay.

— I once got to meet and shake hands with Bob Mould’s parents. It was that same summer of ’84, in Rhode Island. Mom and dad were touring the country, stopping in on the band’s performances. Bob himself introduced me to them.

— Greg Norton once sat patiently backstage while I peppered him with inane questions for a fanzine article I was writing.

— It was Grant, though, who was always the friendliest and most approachable of the three. I remember a night, between sets down at The Living Room in Providence, chatting with him in the parking lot. He was snacking on slices of cheese, when a stray dog came ambling over. Grant shared his cheese with the dog, holding up small bits of it, ever higher, making the dog jump for them.

— That was the same show in which Mould, rushing toward the stage for an encore, smashed his head against a ceiling rafter so hard that you could hear it from the parking lot. I have a feeling he remembers that.

GREATEST HITS, MOULD:

1. Eight Miles High (single)

2. Chartered Trips (Zen Arcade)

3. I Apologize (New Day Rising)

4. Gravity (Everything Falls Apart)

5. Crystal (Candy Apple Grey)

6. Real World (Metal Circus)

7. Makes No Sense at All (Flip Your Wig)

8. Celebrated Summer (New Day Rising)

9. Perfect Example (New Day Rising)

10. All This I’ve Done For You (Candy Apple Grey)

GREATEST HITS, HART:

1. Keep Hanging On (Flip Your Wig)

2. Terms of Psychic Warfare (New Day Rising)

3. Pink Turns to Blue (Zen Arcade)

4. Books About UFOs (New Day Rising)

5. It’s Not Funny Anymore (Metal Circus)

6. She’s a Woman [And Now he is a Man] (Warehouse: Songs and Stories)

7. Standing by the Sea (Zen Arcade)

8. Diane (Metal Circus)

9. The Girl Who Lives on Heaven Hill (New Day Rising)

10. Sunshine Superman (Everything Falls Apart)

Now if you’ve stayed with me this far, chances are you’re a pretty big Hüsker fan who won’t mind if I push things an obsessive step further. For you I present the following addendum. You’ve been warned:

I was looking at some photos of Hüsker Dü in their heyday, circa ’84 or ’85. These guys were, to put it one way, well-fed. Greg always kept himself trim and dapper, but Bob and Grant weren’t going hungry, that’s for sure.

It’s only fair, then, that we should revisit the Hüsker discography, making note of various song titles as they should have appeared. That is, with a gastronomical theme…

There’s little on Land Speed Record or Everything Falls Apart to cook with, so let’s start with Metal Circus. Here, Bob sets the table with “MEAL WORLD,” then takes his place in the “LUNCHLINE.” Grant tells us “I’M NOT HUNGRY ANYMORE,” but later opts for some delicious “STEAK DIANE.”

Zen Arcade is a veritable buffet line of fatty faves: Bob cooks up some “CHARRED TIPS.” Later he orders some “PRIME” down at the “NEWEST EATERY.” He’s got a sweet tooth for “THE BIGGEST PIE.” Alas, it’s a “BROKEN COOKIE, BROKEN HEART.” Grant warns that he’s “NEVER COOKING FOR YOU AGAIN,” yet later we find him “STANDING BY THE STOVE,” dreaming of that moment when “BEEF TURNS TO STEW” (“…waiters placing, gently placing, napkins round her plate.”) This is a very long album, and indigestion sets in by the end of side four, closing with the epic, flatulent jam, “REOCCURRING BEANS.”

Prior to Zen Arcade, you might remember, came the Huskers’ famous 7-inch single — its cover of the Byrds’ — or is it Birds’ — classic, “EGGS PILED HIGH.”

On New Day Rising, Grant tells us about “THE GIRL WHO WORKS AT THE BAR & GRILL,” followed on side two by the sugary “BOOKS ABOUT OREOS.” Bob serves up a “CELEBRATED SUPPER.”

Flip Your Wig is, let’s just say, a little thin, though Grant gives us a cooking lesson with “FLEXIBLE FRYER.”

On Candy Apple Pie… er, Gray … again its Grant with the big appetite. His two meaty singles are, “DON’T WANT TO KNOW IF YOU’RE HUNGRY,” and “HUNGRY SOMEHOW.”

The band’s final course is the delectable double LP: Steakhouse: Songs and Stories. Bob sings of “THESE IMPORTED BEERS,” before going gourmet on the plaintive “BED OF SNAILS.” Alas, he has “NO (DINNER) RESERVATIONS.” Grant snacks on some “CHARITY, CHASTITY, PEANUTS AND COKE,” and reminds us that “YOU CAN COOK AT HOME.”