A Trip to Bhutan

All text and photos by Patrick Smith.

April 30, 2018

“Bhutan? Never heard of it.” This I heard over and over again during the weeks leading up to the trip. So, presuming you need an introduction, Bhutan is a small Himalayan kingdom nestled between Tibet and India. “It’s near Nepal,” is how I explained it most of the time. This is true, though it doesn’t actually border that country, a small sliver of India rising up to separate the two.

Our route to Bhutan, encompassing just over 29 hours of flying, went like this: Boston-San Francisco-Dubai-Bangkok-Paro. It was Emirates to Bangkok, and then the little-known Drukair onward to Bhutan. (If you’re traveling to this part of the world, Bangkok, Southeast Asia’s megahub, is the best jumping off point.)

Boston to Bangkok:

You’ll notice some backtracking in that itinerary on the front end, between Boston and San Francisco. This was done for no other reason than to maximize the flight time with Emirates. I had a bucket full of miles to cash in, and the Emirates flight from SFO to Dubai was the longest flight from the U.S. with upgrade seats available. If flying six hours in the wrong direction, with an overnight stay at the SFO Marriott, sounds insane, you’ve probably never flown first class on the Emirates A380: the onboard showers, the fully enclosed suites with your own private closet, the two onboard bars, the caviar and Dom Perignon. And so on.

I’m not claiming that Emirates competes on a level playing field with other carriers. We’ll save that controversy for later. In the meantime, if like me your favorite guilty pleasure in life is sampling the world’s luxury airline cabins, the experience is tough to beat.

An unusually quiet moment in the aft lounge.

Bangkok to Paro:

We airline geeks have lists; airlines that we hope to someday fly on. Drukair, the government-run carrier of Bhutan, was on my list for years, so it was especially exciting to finally be walking up the airstairs and onto a Drukair A319 at Bangkok’s Suvarnabhumi Airport. The carrier also goes by the name Royal Bhutan Airlines, but the local name has more character. The “Druk” (dragon) prefix is a popular trade name in Bhutan, and you’ll see it on banks, hotels, restaurants — and the national airline.

Drukair’s network, centered at Paro airport in the western part of Bhutan, extends to Bangkok, Singapore, Delhi and Mumbai. For years the company was operating the four-engine British Aerospace 146, but has since upgraded to the more modern Airbus A319. The Airbus has good high-altitude, short-runway performance, which is important when your hub airport sits at 7,300 feet with a stubby, 6,400-foot runway. It’s pretty unusual when an airport’s elevation exceeds the length of its longest runway!

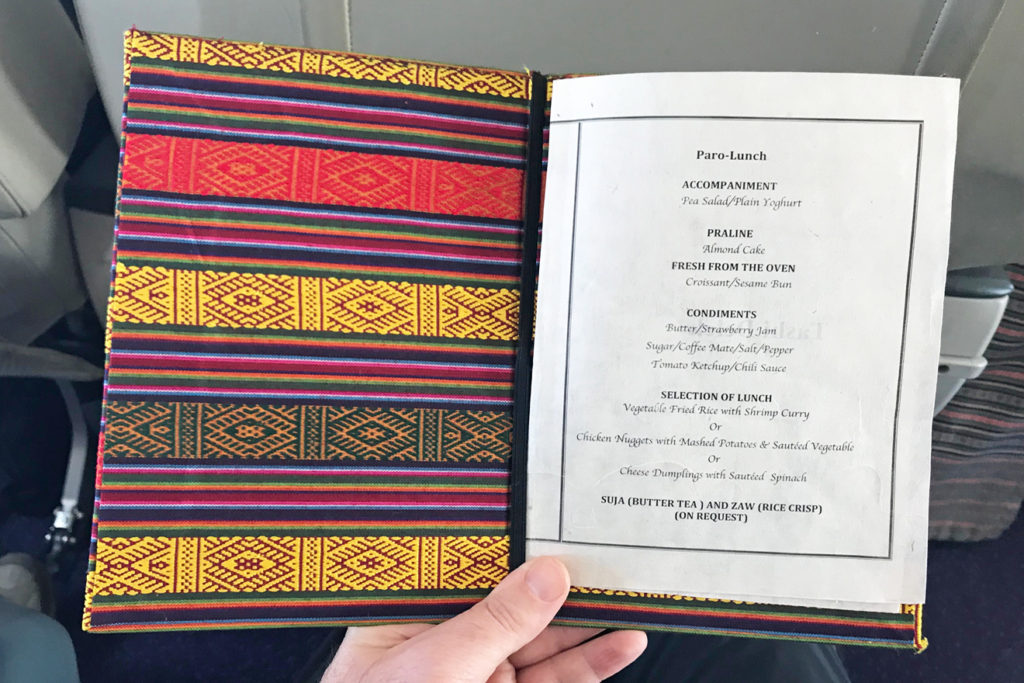

I’d splurged for business class, which on Drukair is a four-abreast, four-row cabin. The seats are the old-fashioned, semi-recliner types; a bit blandly upholstered and perhaps not cleaned as often as they should be. I was appalled when I lifted the center armrest console and discovered a verifiable dune of peanut crumbs and dust. That aside, the experience was perfectly pleasant. The food was tasty and the cabin crew attentive. The menus, stitched with a Bhutanese cloth design, were simple but very pretty.

This was a one-stop flight, with a half-hour layover in Gauhati (Guwahati), India. This was the first time in my life that I boarded an international flight headed to a city that, prior to showing up at the airport, I had never heard of before. I’m very good at geography, which made it all the more mystifying. I stared up at the check-in monitor for a few seconds — Gauhati? — wondering vaguely where I was and where I might be going. I’d later discover that Gauhati has a population of almost a million people. I guess that’s India for you.

Drukair business class menu.

Drukair business class breakfast, fruit course.

Sometimes it’s the little things. Like this lavatory display.

Not your typical airport topography.

During the descent into Paro they played traditional Bhutanese music over the PA. This was an evocative touch, adding a certain exotic-ness to the arrival, especially once the mountains came into view. The initial descent had been through a heavy overcast, occluding that view of Everest I’d been dying to catch, but suddenly the rainclouds gave way to an almost fairy tale panorama of jutting emerald peaks. The lower we got, the more exhilarating it got. The landing gear clunked down at what felt like 15,000 feet, and suddenly we were doing hairpin turns in sheer mountain valleys, with 17,000-foot summits on three sides.

Yeah, I’d read about the arrival into Paro and watched a couple of videos, but that doesn’t prepare you for the visceral thrill of it. Especially that last, very low-altitude turn toward the numbers of runway 33. The expressway visual at LaGuardia has nothing on the landing at Paro. This was the closest I’ve ever come to being truly white-knuckled on a commercial airplane.

Himalayan High. Arrival into Paro.

The expressway visual this ain’t.

Drukair has four A319s in its fleet.

Only two scheduled carriers operate into Paro — Drukair’s privately owned competitor, the unexcitedly (and confusingly) named Bhutan Airlines is the other — and only a few dozen pilots are qualified to fly there. Frankly, this is how it should be. I’d be quite uncomfortable flying into Paro with any crew that wasn’t intimately familiar with the local terrain and its complex arrival and departure patterns.

(So, to be clear, there’s Drukair, a.k.a Royal Bhutan Airlines, and the privately held Bhutan Airlines. If the names aren’t confusing enough, they both fly A319s, in similar paint schemes, on overlapping routes.)

Only two airlines have scheduled service to Paro. Bhutan Airlines is Drukair’s competitor.

Part airport at dusk. Nearby peaks approach 17,000 feet, and Mt. Everest is only a short hop away.

In addition to the dirty seat consoles, two more gripes against Drukair: First, the carrier’s business class lounge in Paro is located outside security and immigration. I imagine this is due to space constraints; the airport is very small. Just the same, nobody wants to relax in a lounge, then have to get their passport stamped and stand in a security line.

And speaking of lines, during check-in, the queue for business class was extraordinarily slow, to the point where virtually all of the economy passengers were able to check in ahead of us. When I attempted to use the economy line, which by that point was empty, I was rudely sent back to the business line and forced to wait another fifteen minutes. Several agents on the economy side now sat behind their podiums with nothing to do, yet refused to check us in.

Paro’s arrival and departure halls are crowded and noisy (departure in particular), but they’re charming in that way of certain small airports. The architecture is in the style of a traditional Bhutanese home, and the decor riffs heavily on the artwork and ornate craftsmanship seen in the country’s many temples, monasteries and dzongs (fortresses).

The terminal at Paro, with mural of the beloved royal family.

Arrivals hall, Bhutan style.

In country:

“Life is suffering.” That’s the first of the Four Pillars of Buddhism, which is somewhat ironic when you discover that Bhutan, in addition to being perhaps the most intensely Buddhist country on earth (prayer flags cover the Bhutan landscape from end to end, like a sort of heavenly confetti), is also one of the most content. This is the country that invented the Gross National Happiness index, and which frequently tops those “world’s happiest countries” lists.

And for a poor nation in an isolated area, little Bhutan seems to have its act together in ways that few developing nations ever do. As Lonely Planet puts it: “Bhutan is one of the few places on earth where compassion is favored over capitalism. Issues of sustainable development, education and health care, and environmental and cultural preservation…are at the forefront of policy making.” The people of Bhutan are happy and comparatively well educated; healthcare is decent and universal. The roads are in good condition, mobile phone service is everywhere, and 98 percent of citizens, even in remote locations, have clean drinking water — an astonishing statistic, as anyone who has traveled in the developing world will acknowledge.

Granted, these things are comparatively easy for a country with fewer than a million people. An honest, uncorrupt government and a Buddhism-based sense of civic responsibility doesn’t hurt.

The Bhutanese government is also acutely concerned about the effects of climate change. The swelling and potential bursting of glacial lakes, for one, threatens to destroy some of the country’s most historic sites. Doing its part, Bhutan currently the only carbon-negative country in the world. It has banned the of chemical fertilizers and no longer imports food that was grown with them. Thus almost all of the country’s produce is organic.

In nearly a week in the country, I never saw a person smoking. Turns out the import or public use of tobacco products is against the law. As are western-style commercial billboards and advertising. There are, for now, no global consumer chains anywhere in Bhutan. No Starbucks, no KFC, no Ikea.

And bring your Tums, or your Prilosec. Pretty much all Bhutanese food, even breakfast, is centered on the chili pepper.

It was all the more surprising, meanwhile, once in the country, after so many friends and acquaintances of mine seemed to have no idea what or where Bhutan was, to encounter so many Americans. Only India, which shares the country’s southern and western borders, sends more tourists. Americans accents were everywhere: in the temples, dzongs, hotels and restaurants. In an age when many Americans seem aggressively incurious, this was encouraging.

Short of turning this into a full-on travelogue, here are a few of the better pictures from the trip. Sightseeing highlights were the beautiful Punakha Valley, and, it hardly needs saying, the thousand-foot climb to the breathtaking Taktshang Goemba — the famous Tiger’s Nest Monastery.

Prayer wheels at the 7th-century Kyichu Lhakhang temple.

Taktshang Goemga: the Tiger’s Nest.

Pagodas at the Duchu La mountain pass.

Monks climbing the stairs at the Punakha Dzong.

Sunset over Punakha Valley

At the temple in Thimpu.

Prayer flags mark the countryside like a heavenly confetti.

At the Punakha Dzong.

Book your tour with Bhutan Swallowtail