Full Circle

April 18, 2023

SO MUCH OF a piloting career is leaving things behind. Change is a constant — new airlines, new planes, new routes — and you’re always saying goodbye. Goodbye to companies, goodbye to colleagues, goodbye to places you loved (or hated) to fly.

And goodbye to airplanes. Seems we’re always jumping from one model to another. Maybe your company finally retired those aging 757s. Maybe you upgraded to captain on a different type, or switched to something bigger and better.

And those airplane farewells aren’t always fond. So it was in 1992 when I completed my final flight in the Beech 99, a twin-engined fifteen-seater from the 60s that was my first assignment as an airline pilot. When I stepped off the stairs of that sad contraption for the last time, I couldn’t run away fast enough. To borrow from an earlier story…

Unpressurized and slow, the Beech 99 was a ridiculous anachronism kept in service by a bottom-feeder airline and its tightfisted owner. The rectangular cabin windows gave it a vintage look, like the windows in a 19th-Century railroad car.

Passengers at Logan would show up planeside in a red bus about twice the size of the plane. Expecting a modern Boeing or Airbus, they were dumped at the foot of a fifteen-passenger wagon built during the Age of Aquarius. I’d be stuffing paper towels into the cockpit window frames to keep out the rainwater while businessmen came up the stairs cursing their travel agents.

A Northeast Express Beech 99, circa 1992.

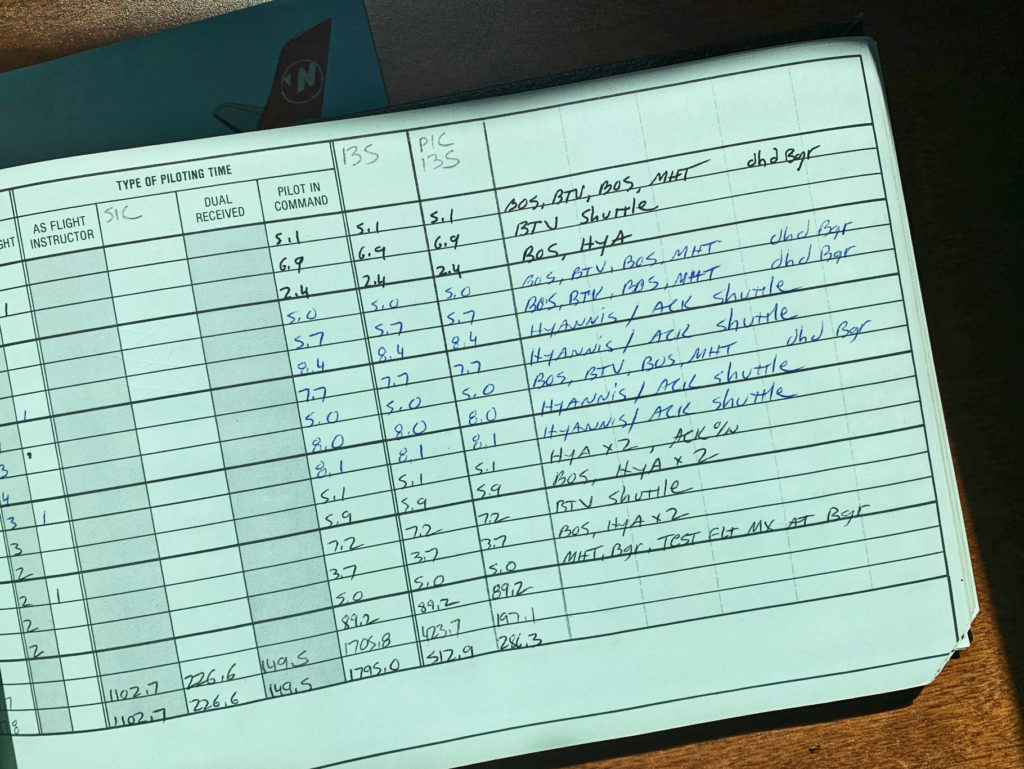

The noise, the cramped cockpit, the shame. Good riddance. My logbook lists my valedictory flight as a run from Augusta, Maine, to Boston, on August 13th, 1992. I don’t remember it, specifically, but my sentiments at the time remain indelible: I never wanted to set foot in a Beech 99 again. And because the plane was an obsolete antique that no respectable airline would operate, never in my dreams did I expect to.

Fast forward to 2023, and I’m sitting with my girlfriend at the airport in Nassau, Bahamas, about to catch a flight to the tiny island of Staniel Cay. We’re booked with something called Flamingo Air, which until three days ago I’d never heard of. Sitting in the departure lounge, I’m idly wondering what kind of plane will be making the half-hour hop to Staniel. A Twin Otter? A Caravan? A Cessna 402?

And then I see it. Or I hear it, actually — that vaguely familiar buzz-rumble of PT-6 engines. I turn and there it is, taxiing towards the building. The awkward, tail-low silhouette and the square windows. The long tapered nose. You can’t be serious. Well fuck me if it isn’t a Beech 99.

“You can’t be serious.”

“What?” says Liz.

“That’s our plane.”

“It’s so cute!”

Nostalgia, you’re thinking, would be the way to approach this. But the only sensation I can muster up is wary combination of disappointment and fear. The Beech 99 was already a tottering piece of junk 32 years ago. To discover one still airworthy is equally hilarious and startling.

And now I have to get in the thing. Being a superstitious sort who can’t help seeking out those nooks of fate where irony and tragedy intersect, I’m convinced I’m going to die.

An agent walks us across the apron towards the plane, which is mostly tombstone-colored. Coming around the wing, I notice the red tail-stand. The 99 is aft-heavy, and boarding has to be staggered to keep it from plopping onto its tail. At Northeast we’d hold the thing up with our shoulders until the forward rows were full. Then after landing we’d run back and do it again.

Going up stairs I catch a view of the tail, decked out in a colorful design of the famous swimming pigs of Big Major Cay. The charm of the image is a little hard to savor because the decal is webbed and cracked and peeling, giving the fin the look of a shattered window.

“All the way forward,” the agent tells me. I climb inside and go to the first row, just behind the pilots. I have to turn sideways because there isn’t enough legroom between my seat and the copilot’s. There’s no cockpit door, of course. At Northeast Express, some of our 99s had curtains. Not this one. The copilot’s shoulder is inches from my face.

It all comes back to me, the details suddenly familiar, even after three decades. The comically small seats and the dearth of headroom, the wing spar cutting across the middle of the cabin floor. The grime and the chipped paint and broken-off moulding. The sun-baked upholstery and the scratched-up plastic windows. The shambles of it all.

Elizabeth eyes me cheerfully, asks me to take her picture. To her this is all great fun. She has no idea of this rattletrap’s significance in my life, or the fact that I’m terrified of it.

I look at the instrument panel. More memories, none of them especially welcome. The toy-sized artificial horizon, the torque gauges, the radio panel straight from a 1970s Piper Cherokee. Theres a primitive GPS, at least, which is something we didn’t have in the early 90s. Several of the annunciatior panel lenses are cracked or missing. The whole thing has the look and feel of a military surplus plane reassembled in someone’s garage.

I recall my first-ever time at the controls of this thing. “It seems like yesterday,” I might say. But it doesn’t. It seems like when it was: October of 1990. On the glamorous route between Manchester, New Hampshire, and Boston — a flight even shorter than this one. I remember cutting my knuckles on the cabin door latch the first time I closed it, flying with bloody fingers.

Off we go. The copilot’s sun visor is broken in six places. It’s turned to the side, and as we accelerate for takeoff it slips from its mount and lands in my lap. I place it on the floor.

The plane is louder than I remembered, and with every seat taken our takeoff roll seems to go on forever. Once airborne, it shimmies and wobbles as it climbs, as if aggravated by its own lack of strength.

At last we reach 5,500 feet and the pilots level off. Takeoff is the most inherently dangerous part of any flight, and I feel better now with the ground a mile below. I relax a little — at least until I glance at the engine gauges and notice the RPM indicator for the left engine sitting at zero. The propeller is still happily turning, thank goodness, so clearly the instrument is kaput. I don’t think that would’ve been “deferrable,” as we put it, back at Northeast Express. Not a big deal, but the little things are adding up.

Elizabeth is looking out the window. The scenery as we near the Exumas chain is unworldly, a psychedelic swirl of blue and cream, sandbar and sea. At least someone is enjoying it.

I already know that I’m going to write about this. Assuming I survive, of course. The question is how. What will the angle be? Should I interview the pilots? The captain is an older guy who looks like a lifer, not some kid building experience with his eyes on a better job elsewhere. He’s not saying goodbye. He must have some stories, flying around the Bahamas all these years, dodging storms, landing on tiny runways. This is the kind of flying highly dependent on seat-of-the-pants skills and local knowledge.

Maybe that should be my article. I jot a few things in my notebook, my handwriting vibrating in time with the engines. But ultimately I decide that I don’t care. I don’t care about the nuances of flying in the Bahamas. I don’t care about local knowledge or the captain’s derring-do. I just want off this thing before the coast guard is fishing my half-eaten body out of some barracuda-infested reef.

And that — this — is my article.

There’s a warbling as we start down, the propellers out of synch as the power comes back. I see an island in the distance, a candy-bar landing airstrip at the center of it. A few minutes later the gear drops. If either pilot says so much as a word over the radio, I don’t notice it.

We whistle over the rocky edge of Staniel and settle onto the pavement. The touchdown is feather-smooth, but when the props go into reverse, it sounds like a table saw chewing through plywood.

The runway is three-thousand feet, the captain tells me after shutting down the engines. We chat for a couple of minutes. “I have eleven hundred hours in one of these,” I tell him. I do some quick and depressing math in my head, calculating how many days of my life that works out to.

He seems impressed, or something. And maybe he’s annoyed. There I was in the first row, watching so intently. Back-seat flying, as it were.

“What’s up with that RPM gauge?”

And though we’re safe and sound, for now, I can’t really savor the moment, because the scarier part is yet to come. Landing on a 3,000 foot runway is one thing, taking off is another. Something to worry about for the next five days.

None of this, if you can’t tell, is especially rational. It’s all me. Was that airplane actually unsafe? It was old and cosmetically beat-up, sure, but aside from a malfunctioning non-critical instrument, everything seemed normal. The ones I flew thirty years ago were no different. The pilots are experienced and know what they were doing. Is it safe to fly this airline to Staniel Cay? No doubt.

The danger exists entirely in my head. It’s not about the airplane; it’s about my past. I’ve been taken hostage, it feels, by the neurotic and the annoying games I play with memories and fate, self-conspiring to wreck my vacation. I can’t help myself.

At the airport we rent a golf cart. That’s how you get around on Staniel, switching from one silly mode of transportation to another. Liz steers us towards the villa while I ruminate. Is there a ferry back to Nassau, I wonder? A fishing boat? Anything but a Beech 99?

Related Story:

THE RIGHT SEAT. PROPELLERS, POLYESTER, AND OTHER MEMORIES.

For more pictures from Staniel Cay, see the author’s Instagram sets.