Thirty Years On

The author and the “Spirit of Moncton,” in 1994.

August 28, 2020

HOW LONG have you been a pilot?

I’m never sure how to answer that question. I had my private pilot’s license at nineteen, but is that the proper benchmark? For a number of years after that, building time as an instructor, I flew nothing bigger than a single-engine four-seater. Define “pilot,” I guess.

What most people are getting at, I think, is how long I’ve been an airline pilot. And the answer to that one is easy: thirty years. Thirty years to the day, in fact. There couldn’t be a worse time for the marking of such a milestone, what with the entire industry bleeding at the jugular. But that’s aviation for you. In this weird business, the forces that shape your career are usually those beyond your control.

And here we are.

I vividly remember “the call.” Nowadays it’s more likely to be a letter, or an email, but in those days it was always a call. It was the summer of 1990, and I remember the phone ringing. I remember standing in the kitchen of the house I grew up in, where I still lived at the time, and picking up the receiver, hoping it was the airline at the other end. And I can recall, pretty much verbatim, the entire conversation between me and a secretary named Vanessa Higgins, as she told me I’d been selected for class. I should report for training on Monday, August 28th, Vanessa explained. The adrenaline rush almost knocked me to the floor.

I date my 30th anniversary not to the moment of that phone call, or to the day, a few months later, when I lifted off the runway with passengers for the first time. To me, it’s the day that I showed up for classroom training, in a rented schoolroom in downtown Bangor, Maine. That was the day I became an employee. Our instructor was a young pilot named Ubi Garcez, who today is a captain for Delta Air Lines. He welcomed us, allowed us to dispense with our neckties, and issued our ID badges, which in those days were little more than pieces of laminated cardboard on which Vanessa had hand-typed our names. My employee number was 421. And typed across the bottom was my date of hire: August 28, 1990 — probably the most significant day of my life, save for my birthday.

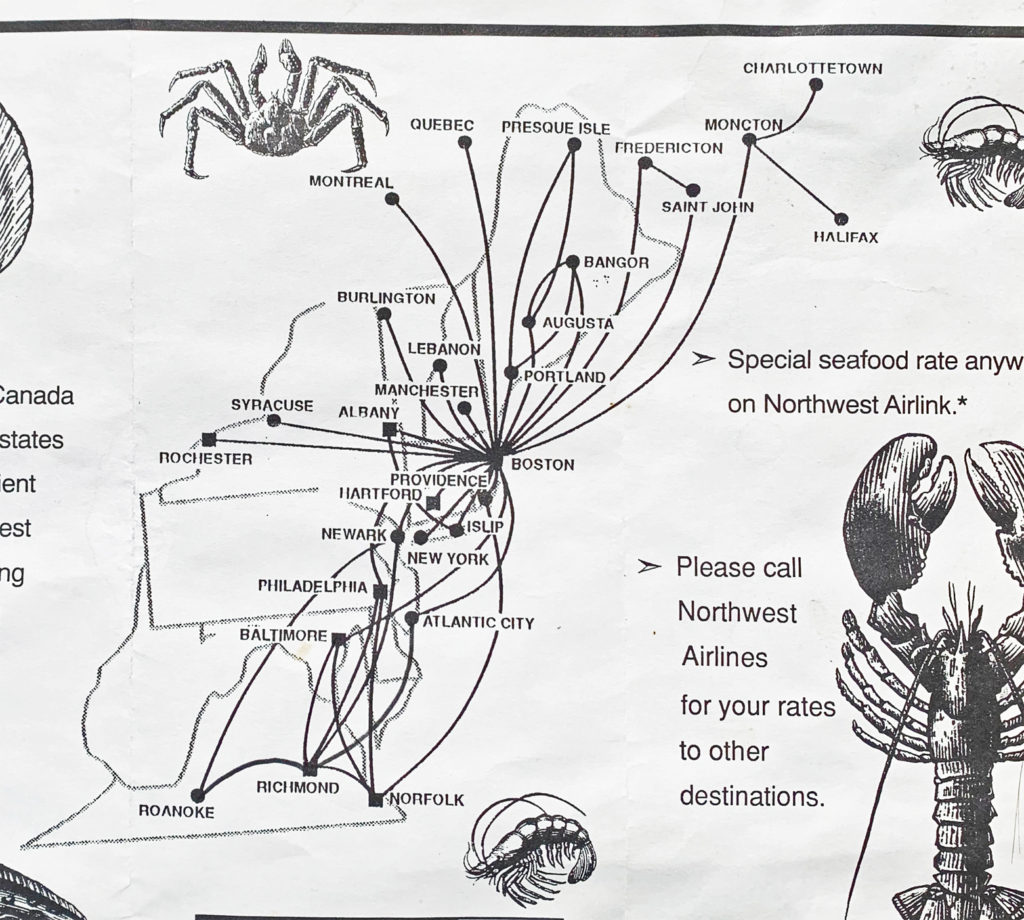

The company was an upstart outfit called Northeast Express Regional Airlines. We were one of the feeder affiliates for Northwest. Our planes, painted in red, said “Northwest Airlink” on the side. The company had been started in Maine, and kept its offices there, but its hub was in Boston, where our small turboprops would bring passengers in from outlying cities and connect them to Northwest’s Boeings and Douglases headed around the country and overseas.

This was the shittiest of shitty airlines. The planes were old and working conditions dismal. My starting salary was $850 per month, gross, and my first aircraft, the Beech-99, was a relic from the 1960s. It had no pressurization or autopilot, and most of its instruments and radios were the same ones I’d seen in the cockpits of the Pipers and Cessnas I’d flown as a novice. But none of that mattered. Salary, working conditions — those things meant nothing to me. All that mattered was to be sitting in that room, with that stupid-looking ID clipped to my pocket.

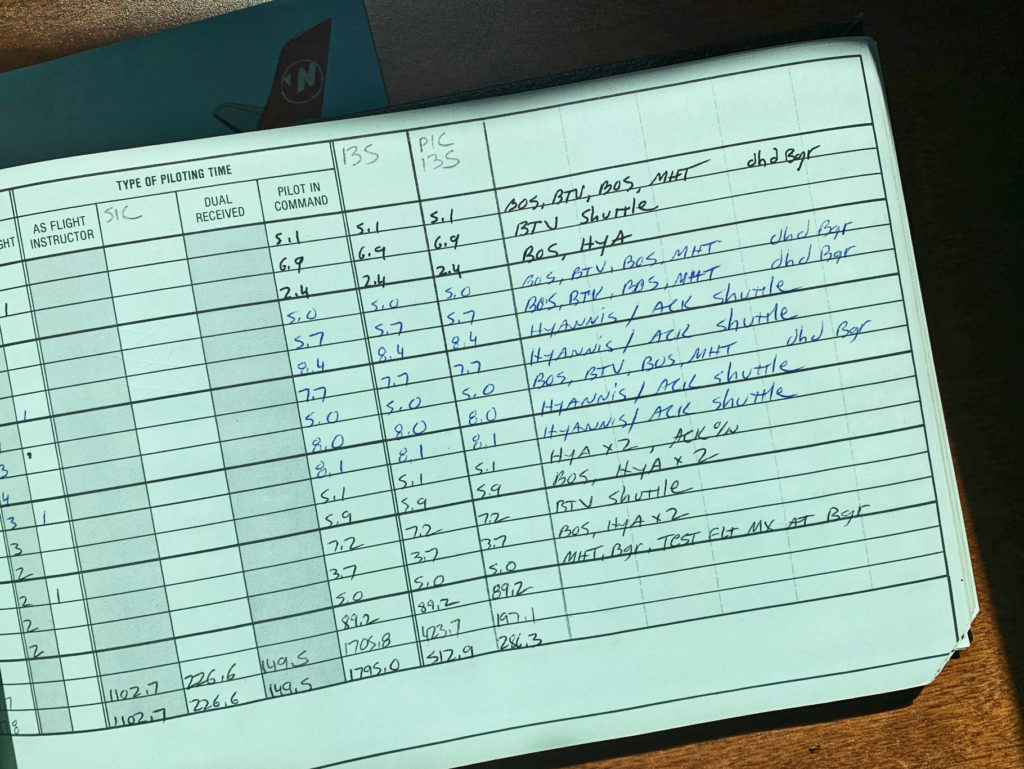

Page from the author’s logbook, 1991.

Pilot jobs in those days were exceptionally competitive. At twenty-four I was the third-youngest in our class of about a dozen. And with 1,600 or so flight hours I was one of the least experienced. I was fortunate to be there at all. I would study the others, wondering where and how I fit in. To this day I remember most of their names and can still hear their accents. One guy had flown business jets, another had flown 727s at Eastern. No, this wasn’t the major leagues. To make a baseball analogy, it was like getting to play for a last-place team at Triple-A in front of about 35 fans. But it was pro ball, so to speak. I’d made it. I was an airline pilot now.

My first “revenue flight,” to use a common if charmless aviation term, didn’t come for another three months. It would take place on October 21, 1990, a date promptly immortalized in yellow highlighter in my logbook. This cherished day involved, among other misfortunes, a drive to Sears at 9:30 in the morning, an hour before my sign-in time, because I’d already lost my tie. (And then the clerk’s face when I told him, “plain black” and “polyester, not silk.”). Then the big moment, in a thickening overcast just before noon, when I would depart on the prestigious Manchester, New Hampshire, to Boston route — a fifteen-minute run frequented, as you’d expect, by Hollywood stars, sheikhs, and dignitaries.

The plane was too tiny for a flight attendant, and I had to close the cabin door myself. Performing this maneuver on my inaugural morning, I turned the handle to secure the latches as trained, deftly and quickly in one smooth motion. What I didn’t see was the popped screw beneath the fitting, across which I would drag all five of my knuckles, cutting myself badly. The door was in the very back, and so I came hobbling up the aisle, stooping to avoid the low ceiling, with my hand wrapped in a bloody napkin.

It was oddly and improbably apropos that my inaugural flight would touch down at Logan International. Airline pilots, especially those new at the game, tend to be migrants, moving from city to city as the tectonics of a seniority list dictate. It’s a rare thing to find yourself operating your very first flight into the airport you grew up with. And I mean that — “grew up with” — in a way that only an airplane nut will understand. As I maneuvered past the Tobin Bridge and along the approach to runway 15R, I squinted toward the parking lot rooftops and the observation deck from which, as a kid, I’d spent so many hours with binoculars. Looking down, I was watching me watch myself, in a sense, celebrating this weird, deeply emotional culmination of nostalgia and accomplishment. If only my hand wasn’t bleeding so much.

A Beech 99 of Northeast Express.

Noisy and slow, the Beech-99 was a ridiculous anachronism kept in service by a bottom-feeder airline and its tightfisted owner. It had rectangular cabin windows that gave it a vintage, almost antique look, like the windows in a 19th-Century railroad car. Passengers at Logan would show up planeside in a red bus about twice the size of the plane. Expecting a 757, they were dumped at the foot of a fifteen-passenger wagon built during the Age of Aquarius. I’d be stuffing paper towels into the cockpit window frames to keep out the rainwater while businessmen came up the stairs cursing their travel agents. They’d sit, seething, refusing to fasten their seat belts and hollering up to cockpit.

“Let’s go! What are you guys doing?”

“I’m preparing the weight and balance manifest, sir.”

“We’re only going to goddamn Newark! What the hell do you need a manifest for?”

And so on. But this was my dream job, so I could only be so embarrassed. Besides, the twelve grand a year was more than I’d been making as a flight instructor.

In addition to just enough money for groceries and car insurance, my job provided the vicarious thrill of our nominal affiliation with Northwest. Our twenty-five or so little planes, like Northwest’s 747s and DC-10s, were done up handsomely in gray and red. Alas, the association ran no deeper — important later, when the paychecks started bouncing — but for now I would code-share my way to glory. When girls asked which airline I flew for, I would answer “Northwest,” with a borderline degree of honesty.

Our uniforms were surplus from the old Bar Harbor Airlines. The owner, Mr. Caruso, had also been the owner at Bar Harbor, and I suspect he had a garage full of remainders. Bar Harbor had been something of a legendary commuter airline in a parochial, New England sort of way, before finally it was eaten by Lorenzo’s Continental. As a kid in the late ’70s I would sit in the backyard and watch those Bar Harbor turboprops going by, one after another, whirring up over the hills of Eastie and Revere. A dozen years later I was handed a vintage Bar Harbor suit, threadbare at the knees and elbows. The lining of my jacket was safety-pinned in place and looked as if a squirrel had chewed the lapels. Some poor Bar Harbor copilot had worn the thing to shreds, tearing the pockets and getting the shoulders soaked with oil and jet fuel. I’m fairly sure it had never been laundered. Standing with my fellow new-hires in our new (old) outfits for a group picture, we looked like crewmembers you might see stepping from a Bulgarian cargo plane on the apron at Entebbe.

A Metroliner of Northeast Express, 1994.

My second plane was the Fairchild Metroliner, a faster and somewhat more sophisticated machine. It was a long, skinny turboprop that resembled a dragonfly, known for its tight quarters and annoying idiosyncrasies. At the Fairchild factory down in San Antonio, the guys with the pocket protectors had faced a challenge: how to take nineteen passengers and make them as uncomfortable as possible. Answer: stuff them side by side into a 6-foot-diameter tube. Attach a pair of the loudest turbine engines ever made, the Garrett TPE-331, and go easy on the soundproofing. All of this for a mere $2.5 million a copy. As captain of this beastly machine, it was my duty not only to safely deliver passengers to their destinations, but also to hide in shame from those chortling and spewing insults: “Does this thing really fly?” and “Man, who did you piss off?”

The answer to that first question was sort of. The Metroliner was equipped with a pair of minimally functioning ailerons and a control wheel in need of a placard marking it “for decorative purposes only.” It was sluggish and unresponsive, is what I’m saying. Somewhere out there is a retired Fairchild engineer feeling very insulted. He deserves it.

Like the 99, the Metro was too small for a cockpit door, allowing for nineteen backseat drivers whose gazes spent more time glued to the instruments than ours did. One particular pilot, whose identity I’ll leave you to guess, had doctored up one of his chart binders with these prying eyes in mind. On the front cover, in oversized stick-on letters, he’d put the words HOW TO FLY, and would stow the book on the floor in full view of the first few rows. During flight he’d pick it up and flip through the pages, eliciting some hearty laughs — or shrieks.

Northeast Express route map, 1994.

In the spring of 1993 I graduated from the Metro to the De Havilland Dash-8. The Dash was a boxy, thirty-seven-passenger turboprop and the biggest thing I’d ever laid my hands on. A new one cost $20 million, and it even had a flight attendant. Only thirteen pilots in the entire company were senior enough to hold a captain’s slot. I was number thirteen. I went for my checkride on July 7th, shortly after my twenty-sixth birthday. For the rest of the summer, I would call the schedulers every morning, begging for overtime. Getting to fly the Dash was a watershed. This was the real thing, an “airliner” in the way the Metro or the 99 could never be, and of all the planes I’ve flown, large or small, it remains my sentimental favorite.

I flew the Dash only briefly, and Northeast Express would be around only for another year. Things began to sour in the spring of ’94. Northwest, unhappy with our reliability, would not renew our contract. We were in bankruptcy by May, and a month later the airline collapsed outright.

The end came on a Monday. I remember that day as vividly as I remember my bloody-knuckle inaugural in New Hampshire four years earlier. No, this wasn’t the collapse of Eastern or Braniff or Pan Am, and I was only twenty-seven, with a whole career ahead of me; still it was heartbreaking — the sight of police cruisers circling our planes, flight attendants crying, and apron workers flinging suitcases into heaps on the tarmac. Thus the bookends of my first airline job were, each in their own way, emotional and unforgettable. That second one, though, I could have done without.

Dash-8 at Kennedy Airport, 1993.

I have only a few mementos from that job. A few scraps of paper, a set of wings, a coffee mug, and a tiny number of poor-quality photos, not one of which, for better or worse, shows the Beech-99.

From that final day at Northeast Express through today, it’s been both an uphill and downhill journey. Many years and five airlines later, I finally made it to the major leagues — to the New York Yankees, as it were, to revisit my baseball analogy. Along the way I’ve endured bankruptcies, multi-year furloughs, and now the COVID-19 debacle that, for all I know at this point, could end the game completely. Highlights, lowlights, life-defining thrills and crushing disappointments, it’s all packed in there.

And it continues. I judge my career as a successful one — I made it further than most pilots do — and it remains a work in progress. However and whenever it reaches its conclusion, at the beginning of it all — and really at the heart of it all — is that first day of class in 1990. Thirty years ago today.