OFFICE PAPER and Other Misfortunes

SOMEWHERE ALONG THE WAY, though I can never pinpoint exactly when it happened to me, the idea of a job — the station of gainful employment — takes on all the gravity and seriousness your parents warned it would. Once again they were right (if overly dramatic about it), and you were wrong (no matter how cool you looked with an orange mohawk).

This is the moment when you stop thinking of work in that easygoing, something-to-do-for-the-summer way and actually begin worrying about it, in the context of an ever-encroaching adulthood. Gone are the days when the sole focus of a job was nothing more weighty than earning enough money for a single, tangible object, be it a new cassette deck or, in my case, airline tickets to Singapore, Hong Kong and Kenya — acquisitions that provided summary release from whichever droning part-time tenure had been endured to save the cash.

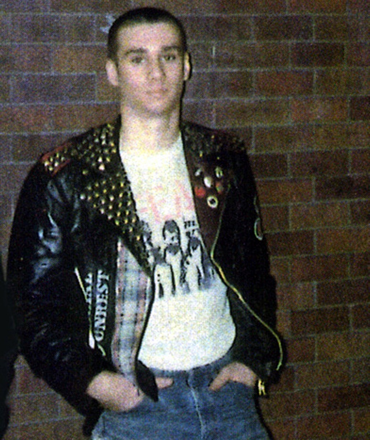

While there are several fabled gauges of when, precisely, we kiss off our youth and embrace — or are floored by — adulthood, that first typed résumé or job interview requiring a tie is, maybe, good a benchmark as any. Thinking back to my teens, and the anarchy-espousing, leather-jacketed social circle I found myself immersed in, I’m surprised that day ever came.

And I’ve still never recovered from, or forgiven, the relentlessly competitive Catholic boys school where I spent grades 9-12. The kind of place where the kids had the admissions addresses of each Ivy League college memorized by sophomore year (also the kind of place that gave us a half-day when Reagan got shot). Talk of careers — part and parcel of some greater, beckoning suburban nirvana — was ceaseless at “The Prep,” as St. John’s Preparatory School pompously called itself. When it was time for SATs, teachers and guidance counselors spoke of that impending Saturday morning with all the fear and seriousness of a pre-dawn air strike briefing, while the Xaverian Brother elders shook their fists and boomed in full Cotton Mather tradition, warning us that lest we buckle down and score at least 600, we would end up back at whatever public high we ran from to attend St. John’s, destined for for some dismal trade school — or, much worse, community college.

Which is exactly where I ended up. As a wannabe rebel and consummate underachiever, the good Brothers’ histrionics had me carving Dead Kennedys logos into the desks with my pocketknife, and I’d leave campus in May, 1984, instilled with a virulent disdain for the notion of gainful employment and a work ethic rife with ideological pranksterism. Indeed, as a graduating senior I was a member of the less than two percent of my class not proceeding immediately to an accredited four-year university.

After a year of post-Xaverian twilight and recovery, I enrolled at a nearby, two-year school that offered an aviation program. I could learn to fly and gain an associate degree at the same time. I was returning to my roots, more or less, following through on my childhood dream of becoming a pilot. Suddenly there I was, in trade school and community college, having made it through four tyrannical years of black robes and Latin only to pursue the very thing for which I least needed them.

I’d require some spending money along the way, of course, and that meant getting a job. Several jobs, it turned out. Several wholly tedious and demeaning part-time stints doing this or that for minimum wage or slightly more. While I can’t speak for everyone, if life has taught me one thing it’s that no matter how awful things turn out in adulthood — no matter how many times you’re laid off or displaced or thrown to the corporate wolves — things will never be quite as unenjoyable or degrading as they were when you were a teenager.

It would take both hands to count the number of blow-off positions I held between the ages of 17 and 21, more than one of which I resigned from with no more ceremony than simply walking home for lunch and never walking back. Such is being young. You get bored and quit, and at this stage in life — a grace period from vocational responsibility — nobody really faults you or cares.

The best terrible job I ever had was in the summer of 1986, two years after I bid farewell to the boat shoes and Izods of St John’s. Roger Clemens was pitching the Red Sox toward another doomed World Series, and I was taking classes and I was earning my pilot ratings at the small woodside airport in Beverly, Massachusetts. I’d found a job driving Subarus around a giant processing lot near Castle Island in South Boston. Enormous ships — great rectangular car-carriers that looked like floating warehouses — would pull in from Yokohama and disgorge their cargo. The Longshoremen (union protected, with good solid salaries) would drive the Subarus onto the docks, and we would then zip them around to an assortment of cleaning, fueling, and primping stations. If you’ve ever bought a new car and wondered where that handful of odometer miles came from, here’s your answer.

We didn’t drive so much as hop — stutter-stepping from station to station. The longest stretch was about quarter-mile, from the washing station to the hot wax machine. Lots of moving around, back and forth, doors opening and closing, opening and closing. The only sounds and sights were those of repetition. In an eight-hour day, I’d probably move a hundred cars a cumulative total of four miles. Having been trained in stop-and-go Boston traffic, I saw this as nothing out of the ordinary. The managers cruised around in vans whistling orders or telling people to slow down, but mostly they sat in the shade playing cards.

It would have been fun to actually navigate the cars down the huge steel planks that led from the ship’s innards to the docks, but the Longshoremen’s contract carefully stipulated a buffer zone of 50 feet around the hull. Only a Longshoreman could drive inside that zone. He’d steer down the ramp, cruise out a few feet, then slam on the brakes and hand over the keys with a snarl.

At five bucks an hour it wasn’t a bad gig for a kid weaning himself away from the raucous, anti-establishment trappings of the punk rock world and back toward a more temporal ambition of flying planes. I was playing with a kind of double-ironic idealism — that of a quasi-rebel realizing the naiveté and disillusionment of one scene, and replacing it with the ultimately more disappointing naiveté and disillusionment of another.

The Castle Island lot was just across the approach end of runways 04L/04R at Logan International, and the sight of the jets arriving low overhead — a source of both inspiration and frustration — kept things interesting on those days when the stench of asphalt-fried guano had most of us in that desperate, what am I doing here mode. Southie being Southie, more than a few of my fellow drivers were illegals from Dublin, and I remember once how the sight of a green and white Aer Lingus 747, like a huge floating bar of Irish Spring, had everyone cheering and clapping. Years later, based at Logan and flying commuter planes, I’d bank down the channel and pivot my wing around that very same processing lot, looking down (sometimes, even, a ship would be unloading) and recalling quite vividly the interior smell of a brand-new ’86 Subaru wagon.

Eventually I had short-lived stints as a courier (both by foot and car), stockroom clerk, and even a stereo speaker repair technician. Starting in 1988 I went through a rapid-fire series of temp jobs. I’d signed up at a couple of different agencies, one or both of which would call at 7 a.m. to offer this or that spirit-breaking task for the week ahead. Often enough I’d turn them down and go back to sleep, an option that is regrettably not among the workplace customs that carry over later in life. Thise go/no-go choice came down to little more than how much pocket money I needed. I was living with my parents, and my only mandatory expense was the $169.96 monthly payment on my burgundy, 1987 Hyundai Excel. To this day, thanks to five depressing years of tearing coupons from a payment book, I remember that amount exactly.

By the summer of ’88 my old girlfriend and I had planned a short a trip to Europe together, a vacation that would be financed entirely by lousy temp jobs (and which would conclude, even more ignominiously, in a Copenhagen hotel room with the love of my life demanding I hand over her return ticket under the threat of throwing my camera out the window. But that’s another story.)

If you’ve ever dabbled in temp jobs, you’ll understand how such assignments can be far more traumatizing than anything withstood during childhood, adolescence, or full-blown adulthood. I’ll happily endure the worst fifth grade pants-pulling episode, high school hazing, and a dozen airline furloughs before I ever again subject myself to temp work again. Temps are the workplace bottom-feeders, brought in to sort, file, and rearrange the spillover of corporate America, the bulk of which consists of millions upon millions of 8.5 x 11 sheets of office paper that need to be put into one brutally tedious order or another. My alphabetizing skills still attest dutifully to the number of $5.25 an hour filing positions I held three decades ago.

One such assignment took place at a downtown Boston firm that maintained thousands of student loan records. My job was to dig out a file — a fat manila envelope stuffed with data — and either add, subtract, or swap various pages. The pages awaiting placement filled an entire shopping carriage that had been wheeled into the windowless, eighth-floor storage area I worked in. The files were arranged alphabetically; the paperwork within by number. Thus, my numerical and letter sequencing skills were put to the test simultaneously, a kind of worst of both worlds scenario and nightmare embodiment of the average temp’s job description. Usually I toiled as instructed, repeating identical tasks over and over until my own arms began to remind me of the insanely repetitive, anthropomorphic motions of the meat-wrapping machine I used to watch at the supermarket as a little kid.

Once in a while there were openings for jobs that required actual standing or walking. These were, to me, the Holy Grail of temp work, free at last from the wrist-crippling world of filing. Gone were the sounds of paper: the shuffling, the crackling, the sound of an index finger counting through corners of white stock — noises that have a water-torture effect when you’ve heard nothing else over the course of a 40-hour week. For one five-day stretch I handed out promotional flyers at the Hynes Convention Center during a computer show. The freedom born of a job that did not revolve around the sequential arrangement of numbers or letters bordered on euphoria. I could stand in the doorway, near the info desk, or even wander at whim through the crowd of hello-my-name-is conventioneers, presenting my handouts to whomever seemed friendly or good-looking enough to warrant one.

Now and then a chance for full-fledged manual labor came up. A department store over in Everett needed a group of temps to dismantle and haul out an immense pile of scrap metal in its rear parking lot. There were a half-dozen of us: myself and five recent parolees from the Billerica House of Corrections there as part of a work release thing. They all knew each other, and bore strangely, vaguely ominous-sounding nicknames like “Chopper,” “Hacksaw,” and “Jackie Red.” They were decent enough people, and each could pull his weight, measured in pounds of scrap metal, with a lot more strength than I could. Unsupervised, much of the day revolved around whatever duty-shirking entertainment can be had from a pile of rusted girders and poles, such as playing baseball with a tennis ball and a bat-shaped section of pipe.

Apparently there was some whole hierarchy of temp work out there. Rough-cut types and jailbirds got the heavy labor assignments, while students and people like me got the paper pushing. Both were shitty jobs, but at least the sweaty stuff gave you some exercise and kept you away from the offices and their supervisors, whose senses of pride and accomplishment, I might add, were tapped directly from the misfortunes of the only people whose tasks were more meaningless than their own: the temp workers. The ex-cons were welcome company after the snide comments and unctuous smirks delivered my way from innumerable office managers.

So I started requesting the heavy stuff, and getting it. Collar-wise, the transition from faux white to dirty blue was cathartic, and kept me from hanging myself and/or skipping a car payment. I helped assemble the sales racks of a new shoe store in East Boston; I moved pallets; I unloaded trailers. The days flew by.

My life as a temp lasted more than three years. During much of this period I was also flight instructing on the side. I’d earned my instructor’s license up at Beverly and was teaching freelance, driving out to airports and putting flyers on people’s Cessnas and Pipers. Flight instruction, serious as it might sound, was essentially a non-job that netted about eight grand a year, necessitating a second and almost equally pitiful income. One day I’d be shooting ILS approaches and teaching some rich gynecologist how to fly in the fog; the next morning, for the same money, I’d be shoveling bark mulch into a truck.

Looking back, I find it hard to believe that by 1990, only a short time removed from the days of moving Subarus and surreptitiously flinging people’s financial aid folders into the trash, I’d be an airline pilot. But to marvel in that, I suppose, is to measure everything in terms of employment — to see and realize oneself solely in the context of a job, a field, a profession. Is it really that important?

Which is easy for me to say, because I went on to do exactly what I’d always wanted to do. I was never apprehensive about, or second guessed, the hot-and-heavy career that was coming at me full speed. How many others can say that? Most people aren’t so blessed — if indeed (another round of layoffs is always, it seems, just around the corner) that’s the applicable term.

And all of us, for better or worse, progress to the ubiquitous “so what do you do?” of the cocktail party. The trick is to have an answer you’re genuinely proud of. Or, failing that, an answer that sounds that way. And often enough, it’s not what you do, but rather how you got there, that makes the better story.

The author in January, 1985