THE RIGHT SEAT: Polyester, Propellers, and Other Memories

BOSTON, 1991

I REACH FOR THE STARTER TOGGLE, left engine. It’s a scalding morning and there’s no external air, so we’re desperate to get the props turning. Out on the Logan asphalt in July, the little Beech-99 becomes a sweatbox, and passengers won’t be pleased if their crew keels over from heatstroke.

These midsummer flights to Nantucket are the worst. We’re always full and the island-bound passengers are cranky and petulant. Today we’re loaded to max weight, with fifteen passengers — all from tony Boston suburbs, decked out identically in mirrored aviator glasses, straw hats and Tevas — and a luggage hold bursting with wicker from Crate & Barrel. After several minutes of organizing carry-ons and dusting off whichever unfortunate soul managed to trip over the center cabin wing spar, it’s time to wipe off the sweat and get started. “Let’s go,” I say. There’s a tattered checklist in my hand, soggy with perspiration.

The toggle clicks into place and we immediately hear the grainy whine of the turbines. The propeller begins to spin, and a small white needle shows the fuel flow. But twenty seconds later there’s a problem. There’s no combustion. Great. So I release the switch and everything stops. We wait the allotted time so the starter won’t overheat, repeat the checklist, and try again. Same result. The engine is turning, but it’s not running. What’s missing, I notice, is the click-click-click of the igniters. For some reason they aren’t firing.

“Kathy, “ I say quietly, “Can you see if there’s a circuit breaker popped?” I can feel eyes on me. The first passenger row is only inches behind us, without so much as a curtain separating cockpit from cabin. “Ignition, left side?”

A diminutive blond, Kathy is my first officer and something of a celebrity around campus. Her story is an unusual one. She’s one of a select few who, through no small effort, had been a flight attendant before becoming a pilot. She had worked the aisles at Delta before giving up the peanuts—and most of her salary—for propellers. Is this what she expected, I wonder: taking orders in a sweltering, thirty-year-old contraption not much larger than her car?

The Beech 99 “Airliner”

The breakers are secure, Kathy reports, running her hand across the panel the way one surfs for an errant wallpaper seam. She motions toward the backup radio, her eyebrows forming a question mark. I nod, and she twists in the frequency.

“Maintenance, this is aircraft 804, are you there?” We’ll wait ten minutes for the mechanics now, while the inside temp hits 106.

A turboprop engine is, at heart, a jet engine. Combusted gases spin the turbines; the turbines spin the compressors and the propeller. It’s the combustion part that we’re missing.

After an embarrassing PA to our aggrieved customers, who by now are checking the ferry schedule, I notice the woman directly behind me has a giant wicker beach bag balanced on her lap. Somehow we’d missed it. “I’m sorry,” I say to her. “You’ll need to stow that bag. It can’t rest on your lap for takeoff.”

“Takeoff?” she says. Then she pauses, lowering her aviators and clearing her throat. “Maybe you oughta see if you can get the fucking plane started before you worry about my fucking luggage.”

As she glares at me with insolently pursed lips, the woman’s glasses reflect the pained face of a very hot and very disappointed young captain — one who, barely past his 24th birthday, often finds that the hardest thing about his job is resisting the urge to take it for granted. I restrain myself and manage a smile, a brittle smirk. I restrain myself not on behalf of Northwest Airlink, in whose employ I toil in kiln-like summer heat, but on behalf of the twelve year-old kid I used to be, not all that long ago, whose dream of dreams was to someday wear the wings and epaulets of an airline pilot. If living out that dream means taking abuse along the way from an asshole passenger or two, well that’s the price I pay.

View of New York City from a Beech-99, circa 1991.

Although I have only hazy memories of the day I first soloed a small airplane, I am able to recollect my first day as an airline pilot in uncannily vivid detail. It was October 21, 1990 — a date promptly immortalized in yellow Hi-Liter in my logbook. Despite the absurdly low salary I’d be earning, I couldn’t have been happier.

This cherished day would involve, among other things, a drive to Sears at 9:30 in the morning, an hour before my sign-in time, because I’d already lost my tie. And then the clerk’s face when I told him “plain black” and “polyester, not silk.” Then the big moment, in a thickening overcast just before noon, when I would depart on the prestigious Manchester, New Hampshire, to Boston route — the twenty-minute run frequented, as you’d expect, by Hollywood stars, sheikhs and dignitaries.

The plane was too tiny for a flight attendant, and I had to close the cabin door myself. Performing this maneuver on my inaugural morning, I turned the handle to secure the latches as trained, deftly and quickly in one smooth motion. What I didn’t see was the popped screw beneath the fitting, across which I would drag all five of my knuckles, cutting myself badly. The door was in the very back, so I came hobbling up the aisle, stooping to avoid the low ceiling, with my hand wrapped in a bloody napkin.

It was oddly and improbably apropos that my inaugural flight would touch down at Logan International. Airline pilots, especially those new at the game, are migrants, moving frequently from city to city as the tectonics of a seniority list dictate. It’s a rare thing indeed to find yourself based at the very airport you grew up with. And I mean that — “grew up with” — in a way that only an airplane nut will understand. On that afternoon in 1990, as I maneuvered past the Tobin Bridge and along the approach to runway 15R, I squinted toward the parking lots and observation deck from which, years earlier, I’d perched with binoculars and notebooks, logging the registration numbers of arriving aircraft.

Our company was a young regional upstart called Northeast Express, and we flew on behalf of Northwest Airlines, code-sharing their flights and using their colors. (Northeast, Northwest, it was confusing to some of our passengers.) Although the airline was growing quickly, it was run with such austerity that we didn’t even have legitimate uniforms. We were given surplus from the old Bar Harbor Airlines. The owner, Mr. Caruso, had also been the owner at Bar Harbor, and I suspect he had a garage full of remainders. Bar Harbor had been something of a legendary commuter airline in a parochial, New England sort of way, before it was eaten by Lorenzo’s Continental.

As a kid in the late ’70s I would sit in the backyard and watch those Bar Harbor turboprops going by, one after another, whirring up over the hills of Eastie and Revere. A dozen years later, I was handed a vintage Bar Harbor suit made of battleship-gray wool, soiled and threadbare in the knees and elbows. The lining of my jacket was safety-pinned in place and looked as if a squirrel had chewed the lapels. Some poor Bar Harbor copilot had worn the thing to shreds, tearing the pockets and getting the shoulders soaked with oil and jet fuel. I’m fairly sure it had never been laundered. Our hardware too—metal emblems for our hats and a set of wings—were tarnished hand-me-downs from Bar Harbor. Standing with my fellow new hires in our new (old) outfits for a group picture, we looked like crewmembers you might see stepping from a Bulgarian cargo plane on the apron at Entebbe.

The uniforms were doled out by a fellow named Harvey Hillson, an old Maine clothier who’d been in the uniform business for ages. Tall, gangly, and bald, he was a fast-talking, distrustful sort who wore heavy, round glasses and chewed a long, unlit cigar. As he explained proper laundering techniques and recommended the use of vinegar to clean soot from our epaulets, his cigar rolled and bobbed like a counterweight, always seeming to perfectly balance the tilt of his head. “And keep your hats on!” Harvey shouted at us, his eyes bugging out. “Some of you guys look so young, you’ll scare the passengers!” He smiled, and his teeth were the color of root beer.

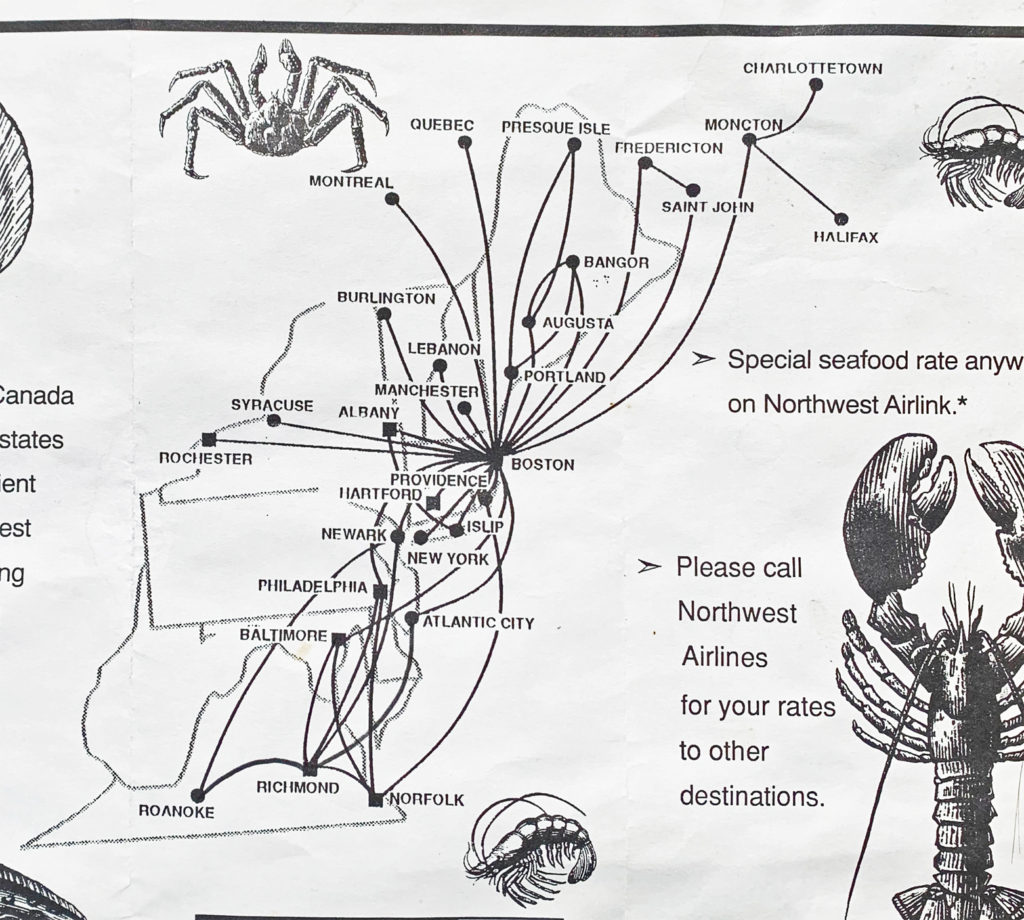

Northeast Express route map, 1994.

One day, in the winter of ’91, Harvey posted a tremendously exciting memo informing us of a uniform revamp. We’d be swapping our gray service station suits for brand new ones—handsome dark navy with gold stripes. We’d get new hardware too; the Bar Harbor eagle, which looked uncannily like the wings-akimbo bird once found on the caps of Göering or Himmler, was out. According to Harvey, our new threads were designed “to keep the airline’s image,” not that it actually had one, “in accordance with Northwest specs.” Ostensibly this made sense, since we were operating in Northwest’s name and painting our planes in its livery, but the truth was Northwest Airlines couldn’t have cared less if we wore banana-colored jumpsuits. It was just a way for Harvey to pull some navy blue wool over our eyes and sell some clothes.

My first airplane was the Beechcraft BE-99, aka the Beech-99, or just “the 99.” Same as those old Bar Harbor planes I’d watched over Revere in fifth grade. This was either sentimentally touching or gruesomely depressing, depending on how you looked at it. Some of the 99s were precisely the same ones, still with a -BH registration suffix painted near the tail. Unpressurized and slow, the plane was a ridiculous anachronism kept in service by a bottom-feeder airline and its tightfisted owner. The rectangular cabin windows gave it a vintage, almost antique look, like the windows in a 19th-Century railroad car. Passengers at Logan would show up planeside in a red bus about twice the size of the plane. Expecting a 757, they were dumped at the foot of a fifteen-passenger wagon built during the Age of Aquarius. I’d be stuffing paper towels into the cockpit window frames to keep out the rainwater while businessmen came up the stairs cursing their travel agents. They’d sit, seething, refusing to fasten their seat belts and hollering up to the cockpit.

“Come on! What are you guys doing?”

“I’m preparing the weight and balance manifest, sir.”

“We’re only going to goddamn Newark! What the hell do you need a manifest for?”

And so on. But hey, this was my dream job, so I could only be so embarrassed. Besides, twelve grand a year was more than I’d been making as a flight instructor.

In addition to just enough money for groceries and car insurance, my job provided the vicarious thrill of a nominal affiliation with Northwest. Our 25 turboprops, like Northwest’s 747s and DC-10s, were painted handsomely in gray and red. Alas, the association ran no deeper — important later, when the paychecks started bouncing — but for now I would code-share my way to glory. When girls asked which airline I flew for, I would answer “Northwest” with a borderline degree of honesty.

My second plane was the Fairchild Metroliner, a more sophisticated nineteen-seater. It was a long, skinny turboprop that resembled a dragonfly, known for its tight quarters and annoying idiosyncrasies. At the Fairchild factory down in San Antonio, the guys with the pocket protectors had faced a challenge: how to take nineteen passengers and make them as uncomfortable as possible. Answer: stuff them side by side into a six-foot diameter tube. Attach a pair of the loudest turbine engines ever made, the Garrett TPE-331, and go easy on the soundproofing. All this for a mere $2.5 million a copy.

As captain of this beastly machine, it was my duty not only to safely deliver passengers to their destinations, but also to hide in shame from those chortling and spewing insults: “Does this thing really fly?” and “Man, who did you piss off?”

A Metroliner of Northeast Express, 1994.

The answer to that first question was sort of. The Metro was equipped with a pair of minimally functioning ailerons and a control wheel in need of a placard marking it “for decorative purposes only.” It was sluggish and unresponsive, is what I’m saying.

Somewhere out there is a retired Fairchild engineer feeling very insulted. He deserves it.

Like the 99, the Metro was too small for a cockpit door, allowing for nineteen backseat drivers whose gazes spent more time glued to the instruments than ours did. One particular pilot, whose identity I’ll leave you to guess, had doctored up one of his chart binders with these prying eyes in mind. On the front cover, in oversized stick-on letters, he’d put the words HOW TO FLY, and would stow the book on the floor in full view of the first few rows. During flight he’d pick it up and flip through the pages, eliciting some hearty laughs — or shrieks.

Another pilot — let’s call him Eric Sanford and say that he came from Lewiston, Maine — thought it would be amusing to dangle a pair of velvet red dice from the overhead standby compass. That one had customers giggling, pointing, slapping him on the back, and sending letters to the FAA. Poor Eric lost a paycheck and earned a blemish on his record that would have recruiters at the major airlines affixing the wrong color stickies to his résumé.

The view of the cockpit was even more entertaining if, as occasionally was the case, somebody had spit-glued a magazine photo across the radar screen. Our radar units, mounted in the middle of the panel and visible all the way to the aft bulkhead, looked like miniature TV sets. At the end of a rotation pilots would clip out a ridiculous picture from a newspaper or magazine, adhere it to the empty screen, and leave it for the next crew. A man in a chef’s hat carrying a wedding cake, I recall, was one memorable choice.

Interior of the SA-227 Metroliner.

In the spring of 1993 I graduated from the Metro to the de Havilland Dash-8. The Dash was a boxy, thirty-seven-passenger turboprop and the biggest thing I’d ever laid my hands on. A new one cost $20 million, and it even had a flight attendant. Only thirteen pilots in the entire company were senior enough to hold a captain’s slot. I was number thirteen. I went for my checkride on July 7th, about a month after my twenty-sixth birthday. For the rest of the summer, I would call the schedulers every morning, begging for overtime. Getting to fly the Dash was a watershed. This was the real thing, an “airliner” in the way the Metro or the 99 could never be, and of all the planes I’ve flown, large or small, it remains my sentimental favorite.

I flew the Dash only briefly, and Northeast Express would be around only for another year. Things began to sour in the spring of ’94. Northwest, unhappy with our reliability, would not renew our contract. We were in bankruptcy by May, and a month later the airline collapsed outright.

The end came on a Monday. I remember that day as vividly as I remember my bloody-knuckle inaugural in New Hampshire, four years earlier. No, this wasn’t the collapse of Eastern or Braniff or Pan Am, and I was only 27 with a whole career ahead of me. But just the same it was heartbreaking — the sight of police cruisers encircling our planes, flight attendants crying and the apron workers flinging suitcases into heaps on the tarmac.

Thus the bookends of my first airline job were, each in their own way, emotional and unforgettable. But that second one I could have done without.

Dash-8 at Kennedy Airport, 1993.